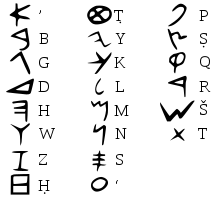

Phoenician alphabet

[3] It developed directly from the Proto-Sinaitic script[4][3] used during the Late Bronze Age, which was derived in turn from Egyptian hieroglyphs.

It was widely disseminated outside of the Canaanite sphere by Phoenician merchants across the Mediterranean, where it was adopted and adapted by other cultures.

The Phoenician alphabet proper was used in Ancient Carthage until the 2nd century BC, where it was used to write the Punic language.

The Phoenician alphabet is a direct continuation of the "Proto-Canaanite" script of the Bronze Age collapse period.

The inscriptions found on the Phoenician arrowheads at al-Khader near Bethlehem and dated c. 1100 BC offered the epigraphists the "missing link" between the two.

[3][7] The Ahiram epitaph, whose dating is controversial, engraved on the sarcophagus of king Ahiram in Byblos, Lebanon, one of five known Byblian royal inscriptions, shows essentially the fully developed Phoenician script,[8][dubious – discuss] although the name "Phoenician" is by convention given to inscriptions beginning in the mid-11th century BC.

[9] Beginning in the 9th century BC, adaptations of the Phoenician alphabet thrived, including Greek, Old Italic and Anatolian scripts.

The other scripts of the time, cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs, employed many complex characters and required long professional training to achieve proficiency;[10] which had restricted literacy to a small elite.

Another reason for its success was the maritime trading culture of Phoenician merchants, which spread the alphabet into parts of North Africa and Southern Europe.

This upset the long-standing status of literacy as an exclusive achievement of royal and religious elites, scribes who used their monopoly on information to control the common population.

[13] The appearance of Phoenician disintegrated many of these class divisions, although many Middle Eastern kingdoms, such as Assyria, Babylonia and Adiabene, would continue to use cuneiform for legal and liturgical matters well into the Common Era.

[15] The Phoenician alphabet was known to the Jewish sages of the Second Temple era, who called it the "Old Hebrew" (Paleo-Hebrew) script.

The theories of independent creation ranged from the idea of a single individual conceiving it, to the Hyksos people forming it from corrupt Egyptian.

There were also distinct variants of the writing system in different parts of Greece, primarily in how those Phoenician characters that did not have an exact match to Greek sounds were used.

The Hebrew, Syriac and Arabic scripts are derived from Aramaic (the latter as a medieval cursive variant of Nabataean).

[dubious – discuss] This includes: Yigael Yadin (1963) went to great lengths to prove that there was actual battle equipment similar to some of the original letter forms named for weapons (samek, zayin).

It has also been theorised that the Brahmi and subsequent Brahmic scripts of the Indian cultural sphere also descended from Aramaic, effectively uniting most of the world's writing systems under one family, although the theory is disputed.

There was, however, a revival of the Phoenician mode of writing later in the Second Temple period, with some instances from the Qumran Caves, such as the Paleo-Hebrew Leviticus scroll dated to the 2nd or 1st century BC.

It has been proposed, notably by Georg Bühler (1898), that the Brahmi script of India (and by extension the derived Indic alphabets) was ultimately derived from the Aramaic script, which would make Phoenician the ancestor of virtually every alphabetic writing system in use today,[32][33] with the notable exception of hangul.

Bühler's suggestion is still entertained in mainstream scholarship, but it has never been proven conclusively, and no definitive scholarly consensus exists.

These were an indigenous set of genetically related semisyllabaries, which suited the phonological characteristics of the Tartessian, Iberian and Celtiberian languages.

Among the distinctive features of Paleohispanic scripts are: ʾ b g d h w z ḥ ṭ y k l m n s ʿ p ṣ q r š t