Origin of speech

[4][5] The human species' unprecedented use of the tongue, lips and other moveable parts seems to place speech in a quite separate category, making its evolutionary emergence an intriguing theoretical challenge in the eyes of many scholars.

Should an impaired child be prevented from hearing or producing sound, its innate capacity to master a language may equally find expression in signing.

In many Australian Aboriginal cultures, a section of the population – perhaps women observing a ritual taboo – traditionally restrict themselves for extended periods to a silent (manually-signed) version of their language.

[17] Then, when released from the taboo, these same individuals resume narrating stories by the fireside or in the dark, switching to pure sound without sacrifice of informational content.

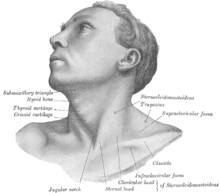

Humans' first recourse is to encode their thoughts in sound – a method which depends on sophisticated capacities for controlling the lips, tongue and other components of the vocal apparatus.

Since this applies to mammals in general, Homo sapiens are exceptional in harnessing mechanisms designed for respiration and ingestion for the radically different requirements of articulate speech.

One controversial suggestion is that certain pre-adaptations for spoken language evolved during a time when ancestral hominins lived close to river banks and lake shores rich in fatty acids and other brain-specific nutrients.

In humans, the tongue has an almost circular sagittal (midline) contour, much of it lying vertically down an extended pharynx, where it is attached to a hyoid bone in a lowered position.

[25] Human tongues are a lot shorter and thinner than other mammals and are composed of a large number of muscles, which helps shape a variety of sounds within the oral cavity.

The diversity of sound production is also increased with the human’s ability to open and close the airway, allowing varying amounts of air to exit through the nose.

During primate evolution, a shift from nocturnal to diurnal activity in tarsiers, monkeys and apes (the haplorhines) brought with it an increased reliance on vision at the expense of olfaction.

Compared with nonhuman primates, humans have significantly enhanced control of breathing, enabling exhalations to be extended and inhalations shortened as we speak.

[28] Evidence from fossil hominins suggests that the necessary enlargement of the vertebral canal, and therefore spinal cord dimensions, may not have occurred in Australopithecus or Homo erectus but was present in the Neanderthals and early modern humans.

[citation needed] Uniquely in the human case, simple contact between the epiglottis and velum is no longer possible, disrupting the normal mammalian separation of the respiratory and digestive tracts during swallowing.

John Ohala argued that the function of the lowered larynx in humans, especially males, is probably to enhance threat displays rather than speech itself.

In response to the objection that the larynx is descended in human females, Fitch suggests that mothers vocalising to protect their infants would also have benefited from this ability.

In 1998, a research team used the size of the hypoglossal canal in the base of fossil skulls in an attempt to estimate the relative number of nerve fibres, claiming on this basis that Middle Pleistocene hominins and Neanderthals had more fine-tuned tongue control than either Australopithecines or apes.

The theory that speech sounds are composite entities constituted by complexes of binary phonetic features was first advanced in 1938 by the Russian linguist Roman Jakobson.

Supporters of this approach view the vowels and consonants recognised by speakers of a particular language or dialect at a particular time as cultural entities of little scientific interest.

By combining the atomic elements or "features" with which all humans are innately equipped, anyone may in principle generate the entire range of vowels and consonants to be found in any of the world's languages, whether past, present or future.

Since speakers and listeners are constantly switching roles, the syllable systems actually found in the world's languages turn out to be a compromise between acoustic distinctiveness on the one hand, and articulatory ease on the other.

For example, in de Boer's model, initially vowels are generated randomly, but agents learn from each other as they interact repeatedly over time.

Pierre-Yves Oudeyer developed models which showed that basic neural equipment for adaptive holistic vocal imitation, coupling directly motor and perceptual representations in the brain, can generate spontaneously shared combinatorial systems of vocalisations, including phonotactic patterns, in a society of babbling individuals.

[62][73] These models also characterised how morphological and physiological innate constraints can interact with these self-organised mechanisms to account for both the formation of statistical regularities and diversity in vocalisation systems.

The discovery of mirror neurons in this region, which fire when an action is done or observed specifically with the hand, strongly supports the belief that communication was once accomplished with gestures.

When one points at a specific object or location, mirror neurons in the child fire as though they were doing the action, which results in long-term learning[79] Critics note that for mammals in general, sound turns out to be the best medium in which to encode information for transmission over distances at speed.

Given the probability that this applied also to early humans, it is hard to see why they should have abandoned this efficient method in favour of more costly and cumbersome systems of visual gesturing – only to return to sound at a later stage.

Lacking direct linguistic evidence, specialists in human origins have resorted to the study of anatomical features and genes arguably associated with speech production.

The current worldwide pattern of phonemic diversity potentially contains the statistical signal of the expansion of modern Homo sapiens out of Africa, beginning around 60-70 thousand years ago.

The authors use a natural experiment – the colonization of mainland Southeast Asia on the one hand, the long-isolated Andaman Islands on the other – to estimate the rate at which phonemic diversity increases through time.

1. Exo-labial, 2. Endo-labial, 3. Dental, 4. Alveolar, 5. Post-alveolar, 6. Pre-palatal, 7. Palatal, 8. Velar, 9. Uvular, 10. Pharyngeal, 11. Glottal, 12. Epiglottal, 13. Radical, 14. Postero-dorsal, 15. Antero-dorsal, 16. Laminal, 17. Apical, 18. Sub-apical