Ornithology

[3] While early ornithology was principally concerned with descriptions and distributions of species, ornithologists today seek answers to very specific questions, often using birds as models to test hypotheses or predictions based on theories.

Other old writings such as the Vedas (1500–800 BC) demonstrate the careful observation of avian life histories and include the earliest reference to the habit of brood parasitism by the Asian koel (Eudynamys scolopaceus).

However, he also introduced and propagated several myths, such as the idea that swallows hibernated in winter, although he noted that cranes migrated from the steppes of Scythia to the marshes at the headwaters of the Nile.

Their nests had not been seen, and they were believed to grow by transformations of goose barnacles, an idea that became prevalent from around the 11th century and noted by Bishop Giraldus Cambrensis (Gerald of Wales) in Topographia Hiberniae (1187).

Michael Scotus from Scotland made a Latin translation of Aristotle's work on animals from Arabic here around 1215, which was disseminated widely and was the first time in a millennium that this foundational text on zoology became available to Europeans.

Frederick II eventually wrote his own treatise on falconry, the De arte venandi cum avibus, in which he related his ornithological observations and the results of the hunts and experiments his court enjoyed performing.

Like Gesner, Ulisse Aldrovandi, an encyclopedic naturalist, began a 14-volume natural history with three volumes on birds, entitled ornithologiae hoc est de avibus historiae libri XII, which was published from 1599 to 1603.

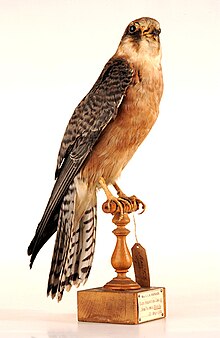

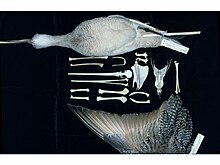

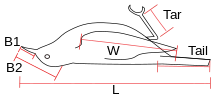

[28][34] In the 17th century, Francis Willughby (1635–1672) and John Ray (1627–1705) created the first major system of bird classification that was based on function and morphology rather than on form or behaviour.

[35] The earliest list of British birds, Pinax Rerum Naturalium Britannicarum, was written by Christopher Merrett in 1667, but authors such as John Ray considered it of little value.

[36] Ray did, however, value the expertise of the naturalist Sir Thomas Browne (1605–82), who not only answered his queries on ornithological identification and nomenclature, but also those of Willoughby and Merrett in letter correspondence.

Browne himself in his lifetime kept an eagle, owl, cormorant, bittern, and ostrich, penned a tract on falconry, and introduced the words "incubation" and "oviparous" into the English language.

Louis Pierre Vieillot (1748–1831) spent 10 years studying North American birds and wrote the Histoire naturelle des oiseaux de l'Amerique septentrionale (1807–1808?).

The emergence of ornithology as a scientific discipline began in the 18th century, when Mark Catesby published his two-volume Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, a landmark work which included 220 hand-painted engravings and was the basis for many of the species Carl Linnaeus described in the 1758 Systema Naturae.

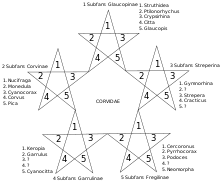

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (1775–1854), his student Johann Baptist von Spix (1781–1826), and several others believed that a hidden and innate mathematical order existed in the forms of birds.

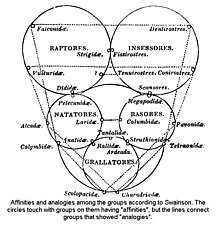

[44][45] A major advance was made by Max Fürbringer in 1888, who established a comprehensive phylogeny of birds based on anatomy, morphology, distribution, and biology.

[51] In 1901, Robert Ridgway wrote in the introduction to The Birds of North and Middle America that: There are two essentially different kinds of ornithology: systematic or scientific, and popular.

Stresemann changed the editorial policy of the journal, leading both to a unification of field and laboratory studies and a shift of research from museums to universities.

[51] Ornithology in the United States continued to be dominated by museum studies of morphological variations, species identities, and geographic distributions, until it was influenced by Stresemann's student Ernst Mayr.

He concluded that population was regulated primarily by density-dependent controls, and also suggested that natural selection produces life-history traits that maximize the fitness of individuals.

The idea of inclusive fitness was used to interpret observations on behaviour and life history, and birds were widely used models for testing hypotheses based on theories postulated by W. D. Hamilton and others.

The use of techniques such as DNA–DNA hybridization to study evolutionary relationships was pioneered by Charles Sibley and Jon Edward Ahlquist, resulting in what is called the Sibley–Ahlquist taxonomy.

The RSPB, born in 1889, grew from a small Croydon-based group of women, including Eliza Phillips, Etta Lemon, Catherine Hall and Hannah Poland.

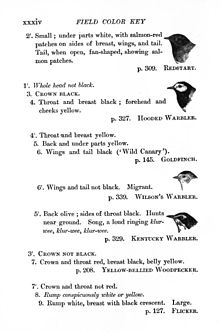

High-power spotting scopes today allow observers to detect minute morphological differences that were earlier possible only by examination of the specimen "in the hand".

Observations are made in the field using carefully designed protocols and the data may be analysed to estimate bird diversity, relative abundance, or absolute population densities.

[84] Camera traps have been found to be a useful tool for the detection and documentation of elusive species, nest predators and in the quantitative analysis of frugivory, seed dispersal and behaviour.

For instance, the variation in the ratios of stable hydrogen isotopes across latitudes makes establishing the origins of migrant birds possible using mass spectrometric analysis of feather samples.

The Emlen funnel, for instance, makes use of a cage with an inkpad at the centre and a conical floor where the ink marks can be counted to identify the direction in which the bird attempts to fly.

Many early studies on the benefits or damages caused by birds in fields were made by analysis of stomach contents and observation of feeding behaviour.

[112][113] Birds are also of medical importance, and their role as carriers of human diseases such as Japanese encephalitis, West Nile virus, and influenza H5N1 have been widely recognized.

Ornithologists contribute to conservation biology by studying the ecology of birds in the wild and identifying the key threats and ways of enhancing the survival of species.