Orphan Train

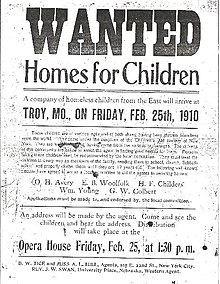

The Orphan Train Movement was a supervised welfare program that transported children from crowded Eastern cities of the United States to foster homes located largely in rural areas of the Midwest short on farming labor.

[2] Criticisms of the program include ineffective screening of caretakers, insufficient follow-ups on placements, and that many children were used as strictly slave farm labor.

[5] During its first year the Children's Aid Society primarily offered boys religious guidance and vocational and academic instruction.

Eventually, the society established the nation's first runaway shelter, the Newsboys' Lodging House, where vagrant boys received inexpensive room and board and basic education.

Brace and his colleagues attempted to find jobs and homes for individual children, but they soon became overwhelmed by the numbers needing placement.

[7] Recognizing the need for labor in the expanding farm country, Brace believed that farmers would welcome homeless children, take them into their homes and treat them as their own.

One reason the term was not used by placement agencies was that less than half of the children who rode the trains were in fact orphans, and as many as 25 percent had two living parents.

And many teenage boys and girls went to orphan train sponsoring organizations simply in search of work or a free ticket out of the city.

For most of the orphan train era, the Children's Aid Society bureaucracy made no distinction between local placements and even its most distant ones.

[6] At a meeting in Dowagiac, Smith played on his audience's sympathy while pointing out that the boys were handy and the girls could be used for all types of housework.

[6] In an account of the trip published by the Children's Aid Society, Smith said that in order to get a child, applicants had to have recommendations from their pastor and a justice of the peace, but it is unlikely that this requirement was strictly enforced.

[11] Orphan train children were placed in homes for free and were expected to serve as an extra pair of hands to help with chores around the farm.

[7] Families were expected to raise them as they would their natural-born children, providing them with decent food and clothing, a "common" education, and $100 when they turned twenty-one.

[1] Babies were easiest to place, but finding homes for children older than 14 was always difficult because of concern that they were too set in their ways or might have bad habits.

[13] Many orphan train children went to live with families that placed orders specifying age, gender, and hair and eye color.

"[12] According to an exhibit panel from the National Orphan Train Complex, the children "took turns giving their names, singing a little ditty, or 'saying a piece.

"[12] According to Sara Jane Richter, professor of history at Oklahoma Panhandle State University, the children often had unpleasant experiences.

[1] Parishioners in the destination regions were asked to accept children, and parish priests provided applications to approved families.

[1] Many rural people viewed the orphan train children with suspicion, as the incorrigible offspring of drunkards and prostitutes.

[6] Small-town ministers, judges, and other local leaders were often reluctant to reject a potential foster parent as unfit if he were also a friend or customer.

"[19] Some residents of placement locations charged that orphan trains were dumping undesirable children from the East onto Western communities.

Alice rode the train because her single mother could not provide for her children; before the journey, they lived on "berries" and "green water.

The Board recommended that paid agents replace or supplement local committees in investigating and reviewing all applications and placements.

A group of white men, described as "just short of a lynch mob," forcibly took the children from the Mexican Indian homes and placed most of them with Anglo families.

Habeas corpus writs should be used "solely in cases of arrest and forcible imprisonment under color or claim of warrant of law," and they should not be used to obtain or transfer the custody of children.

[9] Additionally, Midwestern cities such as Chicago, Cleveland, and St. Louis began to experience the neglected children problems that New York, Boston, and Philadelphia had experienced in the mid-1800s.

[9] Lastly, the need for the orphan train movement decreased as legislation was passed providing in-home family support.

Charities began developing programs to support destitute and needy families limiting the need for intervention to place out children.

[21] The museum is located at the restored Union Pacific Railroad Depot in Concordia which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Founded in 1990[22] and chartered in 2003, this society staffs the volunteer-run museum, conducts historical outreach, researches the stories of riders, and hosts a large annual event akin to a family reunion.