George Orwell

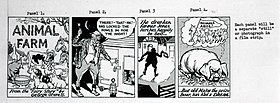

[2][3] Orwell is best known for his allegorical novella Animal Farm (1945) and the dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), although his works also encompass literary criticism, poetry, fiction and polemical journalism.

[7][8] His great-great-grandfather, Charles Blair, was a wealthy slaveowning country gentleman and absentee owner of two Jamaican plantations;[9] hailing from Dorset, he married Lady Mary Fane, daughter of the 8th Earl of Westmorland.

[25] Blair's performance reports suggest he neglected his studies,[25] but he worked with Roger Mynors to produce a college magazine, The Election Times, joined in the production of other publications—College Days and Bubble and Squeak—and participated in the Eton Wall Game.

In December 1921 he left Eton and travelled to join his retired father, mother, and younger sister Avril, who that month had moved to 40 Stradbroke Road, Southwold, Suffolk, the first of their four homes in the town.

In fact he decided to write of "certain aspects of the present that he set out to know" and ventured into the East End of London—the first of the occasional sorties he would make intermittently over a period of five years to discover the world of poverty and the down-and-outers who inhabit it.

In early 1935 Blair met his future wife Eileen O'Shaughnessy, when his landlady, Rosalind Obermeyer, who was studying for a master's degree in psychology at University College London, invited some of her fellow students to a party.

As well as visiting mines, including Grimethorpe, and observing social conditions, he attended meetings of the Communist Party and of Oswald Mosley ("his speech the usual claptrap—The blame for everything was put upon mysterious international gangs of Jews") where he saw the tactics of the Blackshirts.

At the end of the year, concerned by Francisco Franco's military uprising, Orwell decided to go to Spain to take part in the Spanish Civil War on the Republican side.

Under the erroneous impression that he needed papers from some left-wing organisation to cross the frontier, on John Strachey's recommendation he applied unsuccessfully to Harry Pollitt, leader of the British Communist Party.

Miller told Orwell that going to fight in the Civil War out of some sense of obligation or guilt was "sheer stupidity" and that the Englishman's ideas "about combating Fascism, defending democracy, etc., etc., were all baloney".

Eileen volunteered for a post in John McNair's office and with the help of Georges Kopp paid visits to her husband, bringing him English tea, chocolate and cigars.

Observing events from French Morocco, Orwell wrote that they were "only a by-product of the Russian Trotskyist trials and from the start every kind of lie, including flagrant absurdities, has been circulated in the Communist press.

In his book, The International Brigades: Fascism, Freedom and the Spanish Civil War, Giles Tremlett writes that according to Soviet files, Orwell and his wife Eileen were spied on in Barcelona in May 1937.

[103] At the outbreak of the Second World War, Orwell's wife Eileen started working in the Censorship Department of the Ministry of Information in central London, staying during the week with her family in Greenwich.

[108] Early in 1941 he began to write for the American Partisan Review which linked Orwell with the New York Intellectuals who were also anti-Stalinist,[109] and contributed to the Gollancz anthology The Betrayal of the Left, written in the light of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.

For the next four years, Orwell mixed journalistic work—mainly for Tribune, The Observer and the Manchester Evening News, though he also contributed to many small-circulation political and literary magazines—with writing his best-known work, Nineteen Eighty-Four, which was published in 1949.

He was a leading figure in the so-called Shanghai Club (named after a restaurant in Soho) of left-leaning and émigré journalists, among them E. H. Carr, Sebastian Haffner, Isaac Deutscher, Barbara Ward and Jon Kimche.

In late 1945 and early 1946 Orwell made several hopeless and unwelcome marriage proposals to younger women, including Celia Kirwan; Ann Popham, who happened to live in the same block of flats; and Sonia Brownell, one of Connolly's coterie at the Horizon office.

[159] Other writers Orwell admired included Ralph Waldo Emerson, George Gissing, Graham Greene, Herman Melville, Henry Miller, Tobias Smollett, Mark Twain, Joseph Conrad, and Yevgeny Zamyatin.

[172] Raymond Williams in Politics and Letters: Interviews with New Left Review describes Orwell as a "successful impersonation of a plain man who bumps into experience in an unmediated way and tells the truth about it".

Deutscher argued that Orwell had struggled to comprehend the dialectical philosophy of Marxism, demonstrated personal ambivalence towards other strands of socialism and his works such as Nineteen Eighty-Four had been appropriated for the purpose of anti-communist Cold War propaganda.

[198][199] University College London also holds an extensive collection of Orwell's books, including rare and early editions of his works, translations into other languages and titles from his own library.

Described by The Economist as "perhaps the 20th century's best chronicler of English culture",[245] Orwell considered fish and chips, football, the pub, strong tea, cut-price chocolate, the movies, and radio among the chief comforts for the working class.

[249] He appreciated English beer, taken regularly and moderately, despised drinkers of lager,[250] and wrote about an imagined, ideal British pub in his 1946 Evening Standard article, "The Moon Under Water".

[256][257] David Astor described him as looking like a prep school master,[258] while according to the Special Branch dossier, Orwell's tendency to dress "in Bohemian fashion" revealed that the author was "a Communist".

[259] Orwell's confusing approach to matters of social decorum—on the one hand expecting a working-class guest to dress for dinner[260] and, on the other, slurping tea out of a saucer at the BBC canteen[261]—helped stoke his reputation as an English eccentric.

[270] His contradictory and sometimes ambiguous views about the social benefits of religious affiliation mirrored the dichotomies between his public and private lives: Stephen Ingle wrote that it was as if the writer George Orwell "vaunted" his unbelief while Eric Blair the individual retained "a deeply ingrained religiosity".

[278] In Part 2 of The Road to Wigan Pier, published by the Left Book Club, Orwell stated that "a real Socialist is one who wishes—not merely conceives it as desirable, but actively wishes—to see tyranny overthrown".

[297] In 1972, two American authors, Peter Stansky and William Abrahams, produced The Unknown Orwell, an unauthorised account of his early years that lacked any support or contribution from Sonia Brownell.

[299] Crick collated a considerable amount of material in his work, which was published in 1980,[299] but his questioning of the factual accuracy of Orwell's first-person writings led to conflict with Brownell, and she tried to suppress the book.