Ottawa dialect

This and other innovations in pronunciation, in addition to changes in word structure and vocabulary, differentiate Ottawa from other dialects of Ojibwe.

[10] The varieties of Ojibwe form a dialect continuum, a series of adjacent dialects spoken primarily in the area surrounding the Great Lakes as well as in the Canadian provinces of Quebec, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan, with smaller outlying groups in North Dakota, Montana, Alberta, and British Columbia.

[16] These three dialects "show many distinct features, which suggest periods of relative isolation from other varieties of Ojibwe.

[34][35] Communities in Michigan where Ottawa linguistic data has been collected include Peshawbestown, Harbor Springs, Grand Rapids, Mount Pleasant, Bay City, and Cross Village.

"[42] Formal second-language classes attempt to reduce the impact of declining first-language acquisition of Ottawa.

[43] At the time of first contact with Europeans in the early 17th century, Ottawa speakers resided on Manitoulin Island, the Bruce Peninsula, and probably the north and east shores of Georgian Bay.

[44] Since the arrival of Europeans, the population movements of Ottawa speakers have been complex,[44] with extensive migrations and contact with other Ojibwe groups.

[36] As part of a series of population displacements during the same period, an estimated two thousand American Potawatomi speakers from Wisconsin, Michigan and Indiana moved into Ottawa communities in southwestern Ontario.

The subdialects are associated with the ancestry of significant increments of the populations in particular communities and differences in the way the language is named in those locations.

Ottawa fortis consonants are voiceless and phonetically long,[64] and are aspirated in most positions: [pːʰ], [tːʰ], [kːʰ], [tʃːʰ].

[71] The long nasal vowels are iinh ([ĩː]), enh ([ẽː]), aanh ([ãː]), and oonh ([õː]).

Word classes include nouns, verbs, grammatical particles, pronouns, preverbs, and prenouns.

[98] Significant agreement patterns between nouns and verbs involve gender, singular and plural number, as well as obviation.

[104] The most significant of the morphological innovations that characterize Ottawa is the restructuring of the three person prefixes that occur on both nouns and verbs.

[114] Ottawa distinguishes two types of grammatical third person in sentences, marked on both verbs and animate nouns.

Selection and use of proximate or obviative forms is a distinctive aspect of Ottawa syntax that indicates the relative discourse prominence of noun phrases containing third persons; it does not have a direct analogue in English grammar.

[115] Two groups of function words are characteristically Ottawa: the sets of demonstrative pronouns and interrogative adverbs are both distinctive relative to other dialects of Ojibwe.

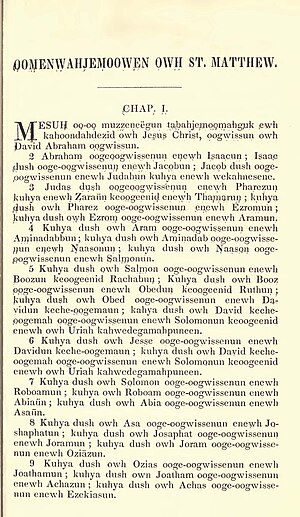

[120] Written representation of Ojibwe dialects, including Ottawa, was introduced by European explorers, missionaries and traders who were speakers of English and French.

[129][21] A conference held in 1996 brought together speakers of all dialects of Ojibwe to review existing writing systems and make proposals for standardization.

[121][131][132] Ottawa speaker Andrew Blackbird wrote a history of his people in English; an appended grammatical description of Ottawa and the Southwestern Ojibwe (Chippewa) dialect also contains vocabulary lists, short phrases, and translations of the Ten Commandments and the Lord's Prayer.

[139] Ottawa speakers from Manitoulin Island contributed articles to Anishinabe Enamiad ('the Praying Indian'), an Ojibwe newspaper started by Franciscan missionaries and published in Harbor Springs, Michigan between 1896 and 1902.

[136] It has been suggested that Ottawa speakers were among the groups that used the Great Lakes Algonquian syllabary, a syllabic writing system derived from a European-based alphabetic orthography,[140] but supporting evidence is weak.

By comparison, folk phonetic spelling approaches to writing Ottawa based on less systematic adaptations of written English or French are more variable and idiosyncratic, and do not always make consistent use of alphabetic letters.

Prominent Ottawa author Basil Johnston has explicitly rejected it, preferring to use a form of folk spelling in which the correspondences between sounds and letters are less systematic.

[38][147] The Ottawa writing system is a minor adaptation of a very similar one used for other dialects of Ojibwe in Ontario and the United States, and widely employed in reference materials and text collections.

[134] Letters of the English alphabet substitute for specialized phonetic symbols, in conjunction with orthographic conventions unique to Ottawa.

[157] French missionaries, particularly members of the Society of Jesus and the Récollets order, documented several dialects of Ojibwe in the 17th and 18th centuries, including unpublished manuscript Ottawa grammatical notes, word lists, and a dictionary.

[133] The first linguistically accurate work was Bloomfield's description of Ottawa as spoken at Walpole Island, Ontario.

Jane Willetts Ettawageshik devoted approximately two years of study in the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians community.

[177] Love Medicine Andrew Medler (1) Ngoding kiwenziinh ngii-noondwaaba a-dbaajmod wshkiniigkwen gii-ndodmaagod iw wiikwebjigan.