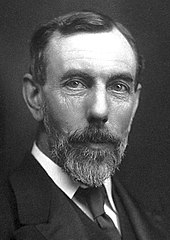

Otto Hahn

Working with Austrian physicist Lise Meitner in the building that now bears their names, they made a series of groundbreaking discoveries, culminating with her isolation of the longest-lived isotope of protactinium in 1918.

With this in mind, and to improve his knowledge of English, Hahn took up a post at University College London in 1904, working under Sir William Ramsay, who was known for having discovered the noble gases.

[14] It was not possible to conduct research in the wood shop, but Alfred Stock, the head of the inorganic chemistry department, let Hahn use a space in one of his two private laboratories.

In subsequent years, mesothorium I assumed great importance because, like radium-226 (discovered by Pierre and Marie Curie), it was ideally suited for use in medical radiation treatment, but cost only half as much to manufacture.

[17][18] In Canada there had been no requirement to be circumspect when addressing the egalitarian New Zealander Rutherford, but many people in Germany found his manner off-putting, and characterised him as an "Anglicised Berliner".

Meitner was allowed to work in the wood shop, which had its own external entrance, but could not enter the rest of the institute, including Hahn's laboratory space upstairs.

Two years later, Hahn became head of the Radioactivity Department of the newly founded Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry (KWIC) in Berlin-Dahlem (in what is today the Hahn-Meitner-Building of the Free University of Berlin).

In September 1917 he was one of three officers, disguised in Austrian uniforms, sent to the Isonzo front in Italy to find a suitable location for an attack, using newly developed rifled minenwerfers that simultaneously hurled hundreds of containers of poison gas onto enemy targets.

[34][32] In 1913, chemists Frederick Soddy and Kasimir Fajans independently observed that alpha decay caused atoms to move down two places on the periodic table, while the loss of two beta particles restored it to its original position.

This book was based on a series of lectures which Professor Hahn had given at Cornell in 1933; it set forth the "laws" for the co-precipitation of minute quantities of radioactive materials when insoluble substances were precipitated from aqueous solutions.

[60] Haber was likewise exempt as a veteran of World War I, but chose to resign his directorship of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry in protest on 30 April 1933.

In August 1933 the administrators of the KWS were alerted that several boxes of Rockefeller Foundation-funded equipment were about to be shipped to Herbert Freundlich, one of the department heads that Hahn had dismissed, who was now working in England.

[63][66] The aging Planck did not seek re-election, and was succeeded in 1937 as president by Carl Bosch, a winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry and the chairman of the board of IG Farben, a company which had bankrolled the Nazi Party since 1932.

[84][85][86] Hahn concluded his by stating emphatically: Vor allem steht ihre chemische Verschiedenheit von allen bisher bekannten Elementen außerhalb jeder Diskussion ("Above all, their chemical distinction from all previously known elements needs no further discussion").

Dieses Ergebnis ist mit den bisherigen Kernvorstellungen sehr schwer in Übereinstimmung zu bringen ("The processes must be neutron capture by uranium-238, which leads to three isomeric nuclei of uranium-239.

[98] Edwin McMillan and Philip Abelson used the cyclotron at the Berkeley Radiation Laboratory to bombard uranium with neutrons, and were able to identify an isotope with a 23-minute half-life that was the daughter of uranium-239, and therefore the real element 93, which they named neptunium.

[101] On 24 April 1939, Paul Harteck and his assistant, Wilhelm Groth, had written to the Armed Forces High Command (OKW), alerting it to the possibility of the development of an atomic bomb.

Hahn was aware that uranium ore was fairly safe in the laboratory, although not so much for the 2,000 female slave labourers from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp who mined it in Oranienburg.

The revelation that Nagasaki had been destroyed by a plutonium bomb came as another shock, as it meant that the Allies had not only been able to successfully conduct uranium enrichment, but had mastered nuclear reactor technology as well.

[119] On 16 November 1945 the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced that Hahn had been awarded the 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry "for his discovery of the fission of heavy atomic nuclei.

[138] Lise Meitner wrote to Hahn, explaining that:Outside of Germany it is considered so obvious that the tradition from the period of Kaiser Wilhelm has been disastrous and that changing the name of the KWS is desirable, that no one understands the resistance against it.

The best people among the English and Americans wish that the best Germans would understand that there should be a definitive break with this tradition, which has brought the entire world and Germany itself the greatest misfortune.

The historian Lawrence Badash wrote: "His wartime recognition of the perversion of science for the construction of weapons, and his postwar activity in planning the direction of his country's scientific endeavours now inclined him increasingly toward being a spokesman for social responsibility.

[147] The following year he initiated and organized the Mainau Declaration of 1955, in which he and other international Nobel Prize-winners called attention to the dangers of atomic weapons and urgently warned the nations of the world against the use of "force as a final resort", and which was issued a week after the similar Russell-Einstein Manifesto.

[151] On 13 November 1957, in the Konzerthaus (Concert Hall) in Vienna, Hahn warned of the "dangers of A- and H-bomb-experiments", and declared that "today war is no means of politics anymore – it will only destroy all countries in the world".

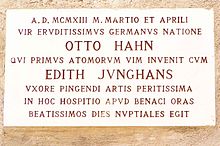

On 22 March 1913 the couple were married in Stettin, where Edith's father, Paul Ferdinand Junghans, was a high-ranking law officer and President of the City Parliament until his death in 1915.

[164][165] The day after his death, the Max Planck Society published the following obituary notice: On 28 July, in his 90th year, our Honorary President Otto Hahn passed away.

His behaviour was completely natural for him, but for the next generations he will serve as a model, regardless of whether one admires in the attitude of Otto Hahn his humane and scientific sense of responsibility or his personal courage.

[168]The Royal Society in London wrote in an obituary: It was remarkable, how, after the war, this rather unassuming scientist who had spent a lifetime in the laboratory, became an effective administrator and an important public figure in Germany.

Hahn, famous as the discoverer of nuclear fission, was respected and trusted for his human qualities, simplicity of manner, transparent honesty, common sense and loyalty.