Lise Meitner

In mid-1938, chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry demonstrated that isotopes of barium could be formed by neutron bombardment of uranium.

[1] She had two older siblings, Gisela and Auguste (Gusti), and four younger: Moriz (Fritz), Carola (Lola), Frida and Walter; all ultimately pursued an advanced education.

[16][18] Encouraged and backed by her father's financial support, Meitner entered the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin, where the renowned physicist Max Planck taught.

[20][21] Attending Planck's lectures did not take up all her time, and Meitner approached Heinrich Rubens, the head of the experimental physics institute, about doing some research.

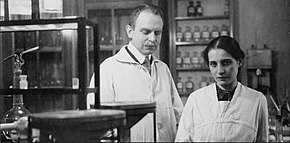

It was not possible to conduct research in the wood shop, but Alfred Stock, the head of the inorganic chemistry department, let Hahn use a space in one of his two private laboratories.

Meitner was allowed to work in the wood shop, which had its own external entrance, but she could not enter the rest of the institute, including Hahn's laboratory space upstairs.

Unlike the universities, the privately funded KWI had no policies excluding women, but Meitner worked without pay as a "guest" in Hahn's section.

[47][49] In 1921, Meitner accepted an invitation from Manne Siegbahn to come to Sweden and give a series of lectures on radioactivity as a visiting professor at Lund University.

[58] Meitner had a Wilson cloud chamber constructed at the KWI for Chemistry, the first one in Berlin, and with her student Kurt Freitag studied the tracks of alpha particles that did not collide with a nucleus.

In 1930, Wolfgang Pauli wrote an open letter to Meitner and Hans Geiger in which he proposed that the continuous spectrum was caused by the emission of a second particle during beta decay, one that had no electric charge and little or no rest mass.

Meitner never tried to conceal her Jewish descent, but initially was exempt from its impact on multiple grounds: she had been employed before 1914, had served in the military during the World War, was an Austrian rather than a German citizen, and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute was a government-industry partnership.

[63] Although Hahn and Meitner remained in charge, their assistants, Otto Erbacher and Kurt Philipp respectively, who were both NSDAP members, were given increasing influence over the day-to-day running of the institute.

[70] After Chadwick discovered the neutron in 1932,[71] Irène Curie and Frédéric Joliot irradiated aluminium foil with alpha particles, and found that this results in a short-lived radioactive isotope of phosphorus.

They were the first scientists to measure the 23-minute half life of the synthetic radioisotope uranium-239 and to establish chemically that it was an isotope of uranium, but with their weak neutron sources they were unable to continue this work to its logical conclusion and identify the real element 93.

[80][81][82] Hahn concluded his by stating emphatically: Vor allem steht ihre chemische Verschiedenheit von allen bisher bekannten Elementen außerhalb jeder Diskussion ('Above all, their chemical distinction from all previously known elements needs no further discussion').

On 9 May, she decided to accept Bohr's invitation to go to Copenhagen, where Frisch worked,[85] but when she went to the Danish consulate to get a travel visa, she was told that Denmark no longer recognised her Austrian passport as valid.

[92] Meitner learned on 26 July that Sweden had granted her permission to enter on her Austrian passport, and two days later she flew to Copenhagen, where she was greeted by Frisch, and stayed with Niels and Margrethe Bohr at their holiday house in Tisvilde.

[100][101] Nonetheless, she had immediately written back to Hahn to say: "At the moment the assumption of such a thoroughgoing breakup seems very difficult to me, but in nuclear physics we have experienced so many surprises, that one cannot unconditionally say: 'It is impossible.

Logically, if barium was formed, the other element must be krypton,[106] but Hahn had mistakenly believed that the atomic masses had to add up to 239 rather than the atomic numbers adding up to 92, and thought it was masurium (technetium), and so did not check for it:[107] Over a series of long-distance phone calls, Meitner and Frisch came up with a simple experiment to bolster their claim: to measure the recoil of the fission fragments, using a Geiger counter with the threshold set above that of the alpha particles.

[114] On 15 November 1945, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced that Hahn had been awarded the 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for "his discovery of the fission of heavy atomic nuclei".

[116] In a 1997 article in the American Physical Society journal Physics Today, Sime and her colleagues Elisabeth Crawford and Mark Walker wrote: It appears that Lise Meitner did not share the 1944 prize because the structure of the Nobel committees was ill-suited to assess interdisciplinary work; because the members of the chemistry committee were unable or unwilling to judge her contribution fairly; and because during the war the Swedish scientists relied on their own limited expertise.

During the war, members of Siegbahn's group saw Meitner as an outsider, withdrawn and depressed; they did not understand the displacement and anxiety common to all refugees, or the trauma of losing friends and relatives to the Holocaust, or the exceptional isolation of a woman who had single mindedly devoted her life to her work.

"[137] On 25 January 1946, Meitner arrived in New York, where she was greeted by her sisters Lola and Frida, and by Frisch, who had made the two-day train trip from Los Alamos.

She went to Durham, North Carolina and saw Hertha Sponer and Hedwig Kohn, and spent an evening in Washington, DC, with James Chadwick, who was now the head of the British Mission to the Manhattan Project.

In 1947, Meitner moved to the Royal Institute of Technology (KTH) in Stockholm, where Gudmund Borelius [sv] established a new facility for atomic research.

Hahn emphasised Meitner's intellectual productivity, and work such as her research on the nuclear shell model, always passing over the reasons for her move to Sweden as quickly as possible.

After breaking her hip in a fall and suffering several small strokes in 1967, Meitner made a partial recovery, but was eventually weakened to the point where she had to move into a Cambridge nursing home.

[152] The President of Germany, Theodor Heuss, awarded Meitner the highest German order for scientists, the peace class of the Pour le Mérite in 1957, the same year as Hahn.

[158] Meitner's diploma bore the words: "For pioneering research in the naturally occurring radioactivities and extensive experimental studies leading to the discovery of fission".

[159] Hahn's diploma was slightly different: "For pioneering research in the naturally occurring radioactivities and extensive experimental studies culminating in the discovery of fission.