8½

Claudia Cardinale, Anouk Aimée, Sandra Milo, Rossella Falk, Barbara Steele, and Eddra Gale portray the various women in Guido's life.

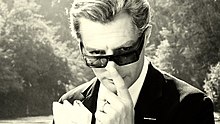

The film was shot in black and white by cinematographer Gianni Di Venanzo and features a score by Nino Rota, with costume and set designs by Piero Gherardi.

Stalled on his new science fiction film that includes thinly veiled autobiographical references, he has lost interest amidst artistic and marital difficulties.

Luisa and Rosella call him on the lie, and Guido slips into a fantasy world where he lords over a harem of women from his life, but a rejected showgirl starts a rebellion.

[10] The working title for 8½ was La bella confusione (The Beautiful Confusion) proposed by co-screenwriter, Ennio Flaiano, but Fellini then "had the simpler idea (which proved entirely wrong) to call it Comedy".

In an October 1960 letter to his colleague Brunello Rondi, Fellini first outlined his film ideas about a man suffering from a creative block: "Well then—a guy (a writer?

Under pressure from his producers, Fellini finally settled on 8½, a self-referential title referring principally (but not exclusively)[15] to the number of films he had directed up to that time.

Giving the order to start production in spring 1962, Fellini signed deals with his producer Rizzoli, fixed dates, had sets constructed, cast Mastroianni, Anouk Aimée, and Sandra Milo in lead roles, and did screen tests at the Scalera Studios in Rome.

[16] The crisis came to a head in April when, sitting in his Cinecittà office, he began a letter to Rizzoli confessing he had "lost his film" and had to abandon the project.

[17] When shooting began on 9 May 1962, Eugene Walter recalled Fellini taking "a little piece of brown paper tape" and sticking it near the viewfinder of the camera.

[18] Perplexed by the seemingly chaotic, incessant improvisation on the set, Deena Boyer, the director's American press officer at the time, asked for a rationale.

8½ marks the first time that actress Claudia Cardinale was allowed to dub her own dialogue; previously her voice was thought to be too throaty and, coupled with her Tunisian accent, was considered undesirable.

[21] In September 1962, Fellini shot the end of the film as initially written: Guido and his wife sit together in the restaurant car of a train bound for Rome.

[24] First released in Italy on 14 February 1963, 8½ received widespread acclaim, with reviewers hailing Fellini as "a genius possessed of a magic touch, a prodigious style".

[24] Italian novelist and critic Alberto Moravia described the film's protagonist, Guido Anselmi, as "obsessed by eroticism, a sadist, a masochist, a self-mythologizer, an adulterer, a clown, a liar and a cheat.

The film is introverted, a sort of private monologue interspersed with glimpses of reality .... Fellini's dreams are always surprising and, in a figurative sense, original, but his memories are pervaded by a deeper, more delicate sentiment.

[25] Reviewing for Corriere della Sera, Giovanni Grazzini underlined that "the beauty of the film lies in its 'confusion'... a mixture of error and truth, reality and dream, stylistic and human values, and in the complete harmony between Fellini's cinematographic language and Guido's rambling imagination.

[30] Premier Plan critics André Bouissy and Raymond Borde argued that the film "has the importance, magnitude, and technical mastery of Citizen Kane.

Fantastic liberality, a total absence of precaution and hypocrisy, absolute dispassionate sincerity, artistic and financial courage these are the characteristics of this incredible undertaking".

[33] Released in the United States on 25 June 1963 by Joseph E. Levine, who had bought the rights sight unseen, the film was screened at the Festival Theatre in New York City in the presence of Fellini and Marcello Mastroianni.

[29] Bosley Crowther praised it in The New York Times as "a piece of entertainment that will really make you sit up straight and think, a movie endowed with the challenge of a fascinating intellectual game ...

[36] Archer Winsten of the New York Post interpreted the film as "a kind of review and summary of Fellini's picture-making" but doubted that it would appeal as directly to the American public as La Dolce Vita had three years earlier: "This is a subtler, more imaginative, less sensational piece of work.

And when they do understand what it is about – the simultaneous creation of a work of art, a philosophy of living together in happiness, and the imposition of each upon the other, they will not be as pleased as if they had attended the exposition of an international scandal".

The site's critical consensus reads: "Inventive, thought-provoking, and funny, 8 1/2 represents the arguable peak of Federico Fellini's many towering feats of cinema.

Later in the year of the film's 1963 release, a group of young Italian writers founded Gruppo '63, a literary collective of the neoavanguardia composed of novelists, reviewers, critics, and poets inspired by 8½ and Umberto Eco's seminal essay, Opera aperta (Open Work).

[62] The following is Kezich's short-list of the films it has inspired: Mickey One (Arthur Penn, 1965), Alex in Wonderland (Paul Mazursky, 1970), Beware of a Holy Whore (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1971), Day for Night (François Truffaut, 1974), All That Jazz (Bob Fosse, 1979), Stardust Memories (Woody Allen, 1980), Sogni d'oro (Nanni Moretti, 1981), Planet Parade (Vadim Abdrashitov, 1984), A King and His Movie (Carlos Sorín, 1986), 1993), Living in Oblivion (Tom DiCillo, 1995), 8½ Women (Peter Greenaway, 1999), and 8½ $ (Grigori Konstantinopolsky, 1999).

8½ has always been a touchstone for me, in so many ways—the freedom, the sense of invention, the underlying rigor and the deep core of longing, the bewitching, physical pull of the camera movements and the compositions...But it also offers an uncanny portrait of being the artist of the moment, trying to tune out all the pressure and the criticism and the adulation and the requests and the advice, and find the space and the calm to simply listen to oneself.

The picture has inspired many movies over the years (including Alex in Wonderland, Stardust Memories, and All That Jazz), and we’ve seen the dilemma of Guido, the hero played by Marcello Mastroianni, repeated many times over in reality—look at the life of Bob Dylan during the period we covered in No Direction Home, to take just one example.

[64]The Tony-winning 1982 Broadway musical Nine (score by Maury Yeston, book by Arthur Kopit) is based on the film, underscoring Guido's obsession with women by making him the only male character.

The play was adapted into a 2009 film of the same name, directed by Rob Marshall and starring Daniel Day-Lewis as Guido alongside Nicole Kidman, Marion Cotillard, Judi Dench, Kate Hudson, Penélope Cruz, Sophia Loren, and Fergie.