Regency of Algiers

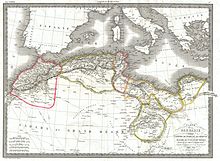

French Algeria (19th–20th centuries) Algerian War (1954–1962) 1990s–2000s 2010s to present The Regency of Algiers[a][b] was an early modern semi-independent Ottoman province and nominal vassal state on the Barbary Coast of North Africa from 1516 to 1830.

As self-proclaimed ghazis gaining popular support and legitimacy from the religious leaders at the expense of hostile local emirs, the Barbarossa brothers and their successors carved a unique corsair state that drew revenue and political power from its naval warfare against Habsburg Spain.

[37][38] In October 1516, Aruj repelled an attack led by the Spanish commander Don Diego de Vera,[39][40] which won him the allegiance of people in the northern part of central Algeria.

[80] The Barbarossa brothers turned the city of Algiers into an Islamic bastion against Catholic Spain in the western Mediterranean,[81][82] making it the capital of what would become the early modern Algerian state.

[85] The beylerbeys of Algiers were usually strongmen who kept most of the Maghreb firmly under Ottoman control, garrisoning the main towns with troops and collecting taxes on land while relying heavily on privateering at sea.

[65][91] In addition, the timar system that granted fertile land to Ottoman elite sipahi cavalrymen was not applied in Algiers; instead, the beylerbeys sent tribute to Constantinople every year after paying off the expenses of the Regency.

[134][135] In 1578 another deputy of Uluj Ali, Hassan Veneziano, led his troops deep into the Sahara to the oases of Tuat in central Algeria in response to pleas from its inhabitants for help against Saadi-allied tribes from Tafilalt.

[136][137] A campaign against Morocco led by Uluj Ali was aborted in 1581,[138] as the Saadian ruler al-Mansur had at first vehemently refused to serve under Selim II's successor Murad III, but agreed to pay annual tribute afterwards.

[62][86] In 1596, Khider Pasha led a revolt in Algiers in an effort to subdue the janissaries with help from Kabyles and Koulouglis—offspring of mixed marriages between Ottoman men and local women and having blood ties to the great indigenous families.

[154] The French built a trading center known as the Bastion de France in the city of El Kala in eastern Algeria,[155] which exported coral legally under its monopoly and wheat illegally.

[189] Khalil Agha, commander-in-chief of the janissaries of Algiers, took advantage of the incident and seized power,[190][191] accusing the pashas sent by the Sublime Porte of corruption and hindering the Regency's affairs with European countries.

[199] In 1671 an English squadron led by Admiral Sir Edward Spragge destroyed seven ships anchored in the harbor at Algiers, causing the corsairs to revolt and kill Agha Ali.

[217] The historian Daniel Panzac stressed:[218] Indeed, privateering was based on two fundamental principles: it was one of the forms of war practiced by the Maghreb against the Christian states, which conferred upon it a dimension that was at one and the same time legitimate and religious; and it was exercised in a framework defined by a state strong enough to enact its rules and control their application.After the Battle of Lepanto, the corsairs broke loose from the Sublime Porte and began to prey on ships from countries at peace with the Ottomans,[177][211] whose peace with Habsburg Spain in 1580 did not concern their vassals, as both the Sovereign Order of Malta and the North African Regencies pursued hostilities.

[237] France launched multiple campaigns against the Regency, first in Jijel in 1664,[238] then when several bombings of Algiers were conducted between 1682 and 1688 in what is known as the Franco-Algerian war,[212] which ended when a 100-year peace treaty was signed between Dey Hussein Mezzo Morto and Louis XIV.

[272] In 1718 Dey Ali Chaouch had Austrian ships captured in clear contradiction to the Treaty of Passarowitz between the Habsburg monarchy and the Ottoman Empire, and ignored an Ottoman-Austrian delegation's demand for compensation.

[296] Led by Mohammed Kebir Bey in 1791,[297] Algiers launched a final assault on Oran, which was retaken after negotiations between Dey Hasan III Pasha and the Spanish Count of Floridablanca.

[304] Meanwhile, payment delays caused frequent janissary revolts, leading to military setbacks[305] as Morocco took possession of Figuig in 1805 and then Tuat and Oujda in 1808,[306][307][308] and Tunisia freed itself from Algerian suzerainty after the wars of 1807 and 1813.

[312] Internal financial problems led Algiers to re-engage in widespread piracy against American and European shipping in the early 19th century, taking full advantage of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

[318][319] Dey Ali Khodja, with support from the Koulouglis and the Kabyles, disposed of the turbulent janissaries and transferred the seat of power and the treasury of the regency from the Djenina Palace [Palais de la Jénina] to the Casbah citadel in 1817.

American political scientist John P. Entelis stresses that Europeans saw Algiers as "the center of pirate activity – that captured the imagination of Europe as a fearsome and vicious enemy".

[334] American historian John Baptist Wolf argued that the local population resented occupation by a republic of foreign "cutthroats and thieves", and that the French "civilizing mission", although carried out by brutal means, offered much to the Algerian people.

[338] Historians John Douglas Ruedy and William Spencer write that the Ottomans in North Africa created an Algerian political entity with all the classical attributes of statehood and a high standard of living.

"[340] Saidouni affirms that Algeria took a similar path as the rest of the North African states that gradually imposed their sovereignty, as it was no different from Muhammad Ali's Egypt, Husainid Tunisia and Alawid Morocco.

[349][44] This government, described by the British philosopher Edmund Burke as "janizarian republick", centered on an Ottoman military elite consisting of several thousands of well-trained, resolute and democratically spirited Anatolian Turkish members of the janissary corps.

Exports included, according to historian William Spencer, "carpets, embroidered handkerchiefs, silk scarves, ostrich feathers,[417] wax, wool, animal hides and skins, dates, and a coarse native linen similar to muslin".

[424] Regional monopolies, such as those granted to the beys of Oran and the French at Bona, further limited trade, while export licenses and concessions for goods like grain, wool, and wax added bureaucratic hurdles.

Al-Zahar reported that the chief of the western province was expected to pay more than 20,000 doro, half that in jewelry, four horses, fifty black slaves, wool from Tlemcen, silk garments from Fez, and twenty quintals each of wax, honey, butter, and walnuts.

The Algerian historian Mouloud Gaid [fr] wrote: "Tlemcen, Mostaganem, Miliana, Médéa, Mila, Constantine, M'sila, Aïn El-Hamma, etc., were always sought after for their green sites, their orchards and their succulent fruits.

[491][492] Architecturally one of the most significant remaining mosques of this era, it exemplifies a mix of Ottoman, North African, and European design elements, with its main dome preceded by a large barrel-vaulted nave.

[493] Of the emblematic Ketchaoua Mosque, built by Dey Hassan III Pasha, Moroccan statesman and historian Abu al-Qasim al-Zayyani wrote in 1795: "The money spent on it...was more than anyone could allow himself to spend except those whom God grants success.