Ottoman Bulgaria

The sabotage of the Conference, by either the British or the Russian Empire (depending on theory), led to the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), whereby the much smaller Principality of Bulgaria, a self-governing, but functionally independent Ottoman vassal state was created.

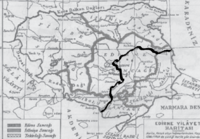

The Ottomans reorganised the Bulgarian territories, dividing them into several vilayets, each ruled by a Sanjakbey or Subasi accountable to the Beylerbey.

Significant parts of the conquered land were parcelled out to the Sultan's followers, who held it as benefices or fiefs (small timar, medium zeamet and large hass) directly from him, or from the Beylerbeys.

[9] Even though they were free to perform their own religious rituals, this had to be done in a manner that was inconspicuous to Muslims, i.e., loud prayers or bell ringing were forbidden.

[10][11] Nevertheless, there were specific categories of rayah who were exempt from nearly all such restrictions, such as the Dervendjis, who guarded important passes, roads, bridges, etc., ore-mining settlements such as Chiprovtsi, etc.

Some of the most important Bulgarian cultural and economic centres in the 19th century owe their development to a former dervendji status, for example, Gabrovo, Dryanovo, Kalofer, Panagyurishte, Kotel, Zheravna.

The exception to this were some groups of the population with specific statute, usually used for auxiliary or rear services, and the infamous blood tax (кръвен данък), also known as devşirme, where young Christian Bulgarian boys were taken from their families, enslaved and converted to Islam and later employed either in the Janissary military corps or the Ottoman administrative system.

[13] While a minority of authors have argued that "some parents were often eager to have their children enrol in the Janissary service that ensured them a successful career and comfort",[14] scholarly consensus leans very much the other way.

Many different ways of avoiding the devshirme are mentioned, including: marrying the boys at the age of 12, mutilating them or having both father and son convert to Islam.

For example, Stephan Gerlach writes:[18] They gather together and one tells another of his native land and of what he heard in church or learned in school there, and they agree among themselves that Muhammad is no prophet and that the Turkish religion is false.

If there is one among them who has some little book or can teach them in some other manner something of God's world, they hear him as diligently as if he were their preacher.When Greek scholar Janus Lascaris visited Constantinople in 1491, he met many Janissaries who not only remembered their former religion and their native land but also favoured their former coreligionists.

Another large group of Tatars was moved by Mehmed I to Thrace in 1418, followed by the relocation of more than 1000 Turkoman families to Northeastern Bulgaria in the 1490s.

[28][29] The goal of this "mixing of peoples" was to quell any unrest in the conquered Balkan states, while simultaneously getting rid of troublemakers in the Ottoman backyard in Anatolia.

While some authors have argued that other factors, such as desire to retain social status, were of greater importance, Turkish writer Halil İnalcık has referred to the desire to stop paying jizya as a primary incentive for conversion to Islam in the Balkans, and Bulgarian researcher Anton Minkov has argued that it was one among several motivating factors.

[31] Two large-scale studies of the causes of adoption of Islam in Bulgaria, one of the Chepino Valley by Dutch Ottomanist Machiel Kiel, and another one of the region of Gotse Delchev in the Western Rhodopes by Evgeni Radushev reveal a complex set of factors behind the process.

These include: pre-existing high population density owing to the late inclusion of the two mountainous regions in the Ottoman system of taxation; immigration of Christian Bulgarians from lowland regions to avoid taxation throughout the 1400s; the relative poverty of the regions; early introduction of local Christian Bulgarians to Islam through contacts with nomadic Yörüks; the nearly constant Ottoman conflict with the Habsburgs from the mid-1500s to the early 1700s; the resulting massive war expenses that led to a sixfold increase in the jizya rate from 1574 to 1691 and the imposition of a war-time avariz tax; the Little Ice Age in the 1600s that caused crop failures and widespread famine; heavy corruption and overtaxation by local landholders—all of which led to a slow, but steady process of Islamisation until the mid-1600s when the tax burden became so unbearable that most of the remaining Christians either converted en masse or left for lowland areas.

Radik (alternatively Radich) was recognised by the Ottomans as a voyvoda of the Sofia region in 1413, but later he turned against them and is regarded as the first hayduk in Bulgarian history.

Those were followed by the Catholic Chiprovtsi Uprising in 1688 and insurrection in Macedonia led by Karposh in 1689, both provoked by the Austrians as part of their long war with the Ottomans.

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca of 1774 gave Russia the right to interfere in Ottoman affairs to protect the Sultan's Christian subjects.

It referred to the separate legal courts pertaining to "personal law" under which religious communities were allowed to rule themselves under their own system.

The foundation of the Exarchate was the direct result of the struggle of the Bulgarian Orthodox population against the domination of the Greek Patriarchate of Constantinople in the 1850s and 1860s.

Nevertheless, Bulgarian religious leaders continued to extend the borders of the Exarchate in the Ottoman Empire by conducting plebiscites in areas contested by both Churches.

Armed resistance to the Ottoman rule escalated in the third quarter of the 19th century and reached its climax with the April Uprising of 1876 that covered part of the ethnically Bulgarian territories of the empire.

[41] To compute total population, male figures are then usually doubled (Bulgarian authors have suggested a coefficient of 1.956, but this has not gained international acceptance).

[59][60][61][44] Ethnoconfessional Groups in the Future Principality of Bulgaria in 1875 [56][62][63][60][64][43][51] At the same time, a flash summary of the results of the Danube Vilayet Census published in the Danube Official Gazette on 18 October 1874 (also covering the Sanjak of Tulça) gave twice as many male Circassian Muhacir, 64,398 vs. 30,573, and slightly fewer "established Muslims" than the final results published in 1875.

[62][64] According to Turkish Ottomanist Koyuncu, 13,825 male Circassians were carried over to the "established Muslims" column and additional 20,000 were left out or simply lost in the carry-over.

[63] Contemporary European geographers, such as German-English Ravenstein, French Bianconi and German Kiepert similarly counted Crimean Tatars with Turks in Islam millet.

[71] In the words of Nusret Pasha, Head of the Silistra Eylaet Colonisation Commission himself, to Hürriyet on 19 October 1868, the Circassians were settled along the Danube in order to serve as live fortification and barrier against Russia.