Constitution of the Ottoman Empire

After Abdul Hamid's political downfall in the 31 March Incident, the Constitution was amended to transfer more power from the sultan and the appointed Senate to the popularly-elected lower house: the Chamber of Deputies.

Moreover, the process of reform itself had imbued a small segment of the elite with the belief that constitutional government would be a desirable check on autocracy and provide it with a better opportunity to influence policy.

Mahmud can be considered the "first real Ottoman reformer",[9] since he took a substantive stand against the janissaries by removing them as an obstacle in the Auspicious Incident.

[citation needed] These movements attempted to bring about real reform not by means of edicts and promises, but by concrete action.

[citation needed] Even after Abdulhamid II suspended the constitution, it was still printed in the salname, or yearbooks made by the Ottoman government.

Midhat Pasha was afraid that Abdul Hamid II would go against his progressive visions; consequently he had an interview with him to assess his personality and to determine if he was on board.

They submitted the first draft on 13 November 1876 which was obstreperously rejected by Abdul Hamid II's ministers on the grounds of the abolishment of the office of the Sadrazam.

[14] There are a total of ten Turkish terms, and the document instead relies on words from Arabic, which Strauss argues is "excessive".

[23] Therefore Strauss wrote that due to its complexity, "A satisfactory translation into Western languages is difficult, if not impossible.

"[23] Max Bilal Heidelberger wrote a direct translation of the Ottoman Turkish version and published it in a book chapter by Tilmann J Röder, "The Separation of Powers: Historical and Comparative Perspectives."

A Latin script rendition of the Ottoman Turkish appeared in 1957, in the Republic of Turkey, in Sened-i İttifaktan Günümüze Türk Anayasa Metinleri, edited by Suna Kili and A. Şeref Gözübüyük and published by Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları.

[26] These versions were respectively printed in Masis, Makikat, Vyzantis, De Castro Press, and La Turquie.

[27] Strauss pointed to the fact that honorifics and other linguistic features in Ottoman Turkish were usually not present in these versions.

[21] The Bulgarian version was re-printed in four other newspapers: Dunav/Tuna, Iztočno Vreme, Napredŭk or Napredǎk ("Progress") and Zornitsa ("Morning Star").

[31] Strauss wrote that the Bulgarian version "corresponds exactly to the French version"; the title page of the copy in the collection of Christo S. Arnaudov (Bulgarian: Христо С. Арнаудовъ; Post-1945 spelling: Христо С. Арнаудов) stated that the work was translated from Ottoman Turkish, but Strauss said this is not the case.

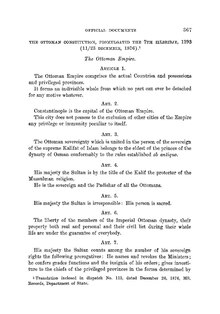

[34] A 1908 issue of the American Journal of International Law printed an Ottoman-produced English version but did not specify its origin.

"[32] Versions in several languages for Christians and Jews used variants of the word "constitution": konstitutsiya in Bulgarian, σύνταγμα (syntagma) in Greek, konstitusyon in Judaeo-Spanish, and ustav in Serbian.

The Russians looked for many ways to become involved in political affairs especially when unrest in the Empire reached their borders.

Their reactions were quite to the contrary from the people; in fact they were completely against it—so much so that the United Kingdom was against supporting the Sublime Porte and criticized their actions as reckless.

Others considered the Ottomans to be grasping for straws in trying to save the Empire; they also labeled it as a fluke of the Sublime Porte and the Sultan.

Fourteen days after this event, on February 14, 1878, Abdul Hamid II took the opportunity to prorogue the parliament, citing social unrest.

Abdul Hamid II, increasingly withdrawn from society to the Yıldız Palace, was therefore able rule the most part of three decades in an absolutist manner.

Many political groups and parties were formed during this period, including the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP).

Despite the latitude it gave to the sovereign, the constitution provided clear evidence of the extent to which European influences operated among a section of the Ottoman bureaucracy.

This showed the effects of the pressure from Europeans on the issue of discrimination of religious minorities within the Ottoman Empire, although, Islam was still the recognized religion of the state.

[46] The constitution also reaffirmed the equality of all Ottoman subjects, including their right to serve in the new Chamber of Deputies.

[48][49] Ultimately, although the constitution created an elected chamber of deputies and an appointed senate, it only placed minimal restriction on the Sultan's power.

Although the basic rights guaranteed in the constitution were not at all insignificant in Ottoman legal history, they were severely limited by the pronouncements of the ruler.

Instead of overcoming sectarian divisions through the institution of universal representation, the elections reinforced the communitarian basis of society by allotting quotas to the various religious communities based on projections of population figures derived from the census of 1844.