Pā

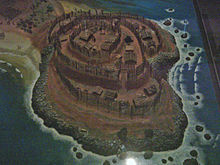

In Māori culture, a great pā represented the mana (prestige or power) and strategic ability of an iwi (tribe or tribal confederacy), as personified by a rangatira (chieftain).

Māori built pā in various defensible locations around the territory (rohe) of an iwi to protect fertile plantation-sites and food supplies.

Over time, some pā may have become more important as places of display and as a symbol of status (tohu rangatira), rather than purely defensive locations.

The simplest pā, the tuwatawata, generally consisted of a single wood palisade around the village stronghold, and several elevated stage levels from which to defend and attack.

The most sophisticated pā was called a pā whakino, which generally included all the other features plus more food storage areas, water wells, more terraces, ramparts, palisades, fighting stages, outpost stages, underground dug-posts, mountain or hill summit areas called "tihi", defended by more multiple wall palisades with underground communication passages, escape passages, elaborate traditionally carved entrance ways, and artistically carved main posts.

Standard features included a community well for long-term supply of water, designated waste areas, an outpost or an elevated stage on a summit on which a pahu would be slung on a frame that when struck would alarm the residents of an attack.

[4] The whare (a Māori dwelling place or hut) of the rangatira and ariki (chiefs) were often built on the summit with a weapons storage.

Pā excavated in Northland have provided numerous clues to Māori tool and weapon manufacturing, including the manufacturing of obsidian (volcanic glass), chert and argillite basalt, flakes, pounamu chisels, adzes, bone and ivory weapons, and an abundance of various hammer tools which had accumulated over hundreds of years.

Chips or flakes of chert were used as drills for pā construction, and for the making process of other industrial tools like Polynesian fish hooks.

Simpler gunfighter pā of the post contact period could be put in place in very limited time scales, sometimes two to fifteen days, but the more complex classic constructions took months of hard labour, and were often rebuilt and improved over many years.

Gunfighter pā could resist bombardment for days with limited casualties although the psychological impact of shelling usually drove out defenders if attackers were patient and had enough ammunition.

[citation needed] Māori's undoubted skill at constructing earthworks evolved from their skill at building traditional pā which, by the late 18th century, involved considerable earthworks to create rua (food storage pits), ditches, earth ramparts and multiple terraces.

Warrior chiefs like Te Ruki Kawiti realised that these properties were a good counter to the greater firepower of the British.

Hōne Heke won the battle and "he carried his point", with the Crown never tried to resurrect the flagstaff at Kororareka while Kawiti lived.

The forts could even include underground bunkers, protected by a deep layer of earth over wooden beams, which sheltered the inhabitants during periods of heavy shelling by artillery.

[12] A limiting factor of the Māori fortifications that were not built as set pieces, however, was the need for the people inhabiting them to leave frequently to cultivate areas for food, or to gather it from the wilderness.

[13] In Māori tradition a pā would also be abandoned if a chief was killed or if some calamity took place that a tohunga (witch doctor/shaman) had attributed to an evil spirit (atua).

The largest of this type was found at Lake Ngaroto, Waikato, the ancient settlement of the Ngāti Apakura, very close to the battle of Hingakaka.