Polynesian navigation

However, as an increasing number of islands in the South Pacific became occupied, and citizenship and national borders became of international importance, this was no longer possible.

[6][7][8] Navigators travelled to small inhabited islands using wayfinding techniques and knowledge passed by oral tradition from master to apprentice, often in the form of song.

Between about 3000 and 1000 BC speakers of Austronesian languages spread through the islands of Southeast Asia – most likely starting out from Taiwan,[9] as tribes whose natives were thought to have previously arrived from mainland South China about 8000 years ago – into the edges of western Micronesia and on into Melanesia, through the Philippines and Indonesia.

This culture, known as Lapita, stands out in the Melanesian archeological record, with its large permanent villages on beach terraces along the coasts.

Particularly characteristic of the Lapita culture is the making of pottery, including a great many vessels of varied shapes, some distinguished by fine patterns and motifs pressed into the clay.

Between about 1300 and 900 BC, the Lapita culture spread 6,000 km (3,700 mi) farther to the east from the Bismarck Archipelago, until it reached as far as Tonga and Samoa.

[17] The pattern of settlement also extended to the north of Samoa to the Tuvaluan atolls, with Tuvalu providing a stepping stone to the founding of Polynesian Outlier communities in Melanesia and Micronesia.

[21] The archeological record supports oral histories of the first peopling of region including both the timing and geographical origins of Polynesian society.

In The Raft Book,[28] a survival guide he wrote for the U.S. military during World War II, Gatty outlined various Polynesian navigation techniques for shipwrecked sailors or aviators to find land.

One such difference is that the zone in which most Polynesian voyaging was carried out was within 20° of the equator, so rising and setting stars did so at an angle that was close to vertical relative to the horizon.

His grandfather and father had passed to Tupaia the knowledge as to the location of the major islands of western Polynesia and the navigation information necessary to voyage to Fiji, Samoa and Tonga.

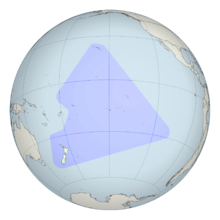

We find it, from New Zealand, in the South, as far as the Sandwich Islands (Hawaiʻi), to the North, and, in another direction, from Easter Island, to the Hebrides (Vanuatu); that is, over an extent of sixty degrees of latitude, or twelve hundred leagues north and south, and eighty-three degrees of longitude, or sixteen hundred and sixty leagues east and west!

How much farther in either direction its colonies reach is not known; but what we know already; in consequence of this and our former voyage, warrants our pronouncing it to be, though perhaps not the most numerous, certainly by far the most extensive, nation upon earth.There is academic debate on the furthest southern extent of Polynesian expansion.

"[52] Oral history describes Ui-te-Rangiora, around the year 650, leading a fleet of Waka Tīwai south until they reached, "a place of bitter cold where rock-like structures rose from a solid sea".

[60] A 2007 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences examined chicken bones at El Arenal, Chile, near the Arauco Peninsula.

In contrast, sequences from two archaeological sites on Easter Island group with an uncommon haplogroup from Indonesia, Japan, and China and may represent a genetic signature of an early Polynesian dispersal.

Interpretations based on poorly sourced and documented modern chicken populations, divorced from the archeological and historical evidence, do not withstand scrutiny.

This theory has attracted limited media attention within California, but most archaeologists of the Tongva and Chumash cultures reject it on the grounds that the independent development of the sewn-plank canoe over several centuries is well-represented in the material record.

[68][69][70] Polynesian contact with the prehispanic Mapuche culture in central-south Chile has been suggested because of apparently similar cultural traits, including words like toki (stone axes and adzes), hand clubs similar to the Māori wahaika, the dalca –a sewn-plank canoe as used on Chiloe Archipelago, the curanto earth oven (Polynesian umu) common in southern Chile, fishing techniques such as stone wall enclosures, palín –a hockey-like game– and other potential parallels.

[71][72] Some strong westerlies and El Niño wind blow directly from central-east Polynesia to the Mapuche region, between Concepción and Chiloe.

According to Andrew Sharp, the explorer Captain James Cook, already familiar with Charles de Brosses's accounts of large groups of Pacific islanders who were driven off course in storms and ended up hundreds of miles away with no idea where they were, encountered in the course of one of his own voyages a castaway group of Tahitians who had become lost at sea in a gale and blown 1000 miles away to the island of Atiu.

Cook wrote that this incident "will serve to explain, better than the thousand conjectures of speculative reasoners, how the detached parts of the earth, and, in particular, how the South Seas, may have been peopled".

Late 19th- and early 20th-century writers such as Abraham Fornander and Percy Smith told of heroic Polynesians migrating in great coordinated fleets from Asia far and wide into present-day Polynesia.

Ethnographic research in the Caroline Islands in Micronesia brought to light the fact that traditional stellar navigational methods were still very much in everyday use there.

The building and testing of proa canoes (wa) inspired by traditional designs, the harnessing of knowledge from skilled Micronesians, as well as voyages using stellar navigation, allowed practical conclusions about the seaworthiness and handling capabilities of traditional Polynesian canoes and allowed a better understanding of the navigational methods that were likely to have been used by the Polynesians and of how they, as people, were adapted to seafaring.

The team claimed to be able to replicate ancient Hawaiian double-hulled canoes capable of sailing across the ocean using strictly traditional voyaging techniques.

Eddie Aikau, a world champion surfer, and part of the crew, attempted to paddle his surfboard to the nearest island to find help.

[82] In New Zealand, a leading Māori navigator and ship builder was Hector Busby, who was also inspired and influenced by Nainoa Thompson and Hokulea's voyage there in 1985.

British-based catamaran designers Hanneke Boon and James Wharram closely followed the hull shape of the traditional Tikopia craft,[84] as represented by Rakeitonga, a 9 m outrigger canoe acquired by the Auckland Museum in 1916.

[86] The 'Lapita Tikopia' and its sistership 'Lapita Anuta' took five months to sail to the islands, following the ancient migration route of the Lapita people into the Pacific.