PAL

A latter evolution of the standard, PALplus, added support for widescreen broadcasts with no loss of vertical image resolution, while retaining compatibility with existing sets.

Almost all of the countries using PAL are currently in the process of conversion, or have already converted transmission standards to DVB, ISDB or DTMB.

[1] Countries in those regions that did not adopt PAL were France,[2] Francophone Africa,[2] several ex-Soviet states,[2] Japan,[3] South Korea, Liberia, Myanmar, the Philippines,[3] and Taiwan.

In the 1950s, the Western European countries began plans to introduce colour television, and were faced with the problem that the NTSC standard demonstrated several weaknesses, including colour tone shifting under poor transmission conditions, which became a major issue considering Europe's geographical and weather-related particularities.

The goal was to provide a colour TV standard for the European picture frequency of 50 fields per second (50 hertz), and finding a way to eliminate the problems with NTSC.

PAL was developed by Walter Bruch at Telefunken in Hanover, West Germany, with important input from Gerhard Mahler [de].

[4] The format was patented by Telefunken in December 1962, citing Bruch as inventor,[5][6] and unveiled to members of the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) on 3 January 1963.

[6] In 1993,[11] an evolution of PAL aimed to improve and enhance format by allowing 16:9 aspect ratio broadcasts, while remaining compatible with existing television receivers,[12] was introduced.

CCIR 625/50 and EIA 525/60 are the proper names for these (line count and field rate) standards; PAL and NTSC on the other hand are methods of encoding colour information in the signal.

"PAL-D", "PAL-N", "PAL-H" and "PAL-K" designations on this section describe PAL decoding methods and are unrelated to broadcast systems with similar names.

This method (known as 'gated NTSC') was adopted by Sony on their 1970s Trinitron sets (KV-1300UB to KV-1330UB), and came in two versions: "PAL-H" and "PAL-K" (averaging over multiple lines).

The SECAM system, on the other hand, uses a frequency modulation scheme on its two line alternate colour subcarriers 4.25000 and 4.40625 MHz.

Early PAL receivers relied on the human eye to do that cancelling; however, this resulted in a comb-like effect known as Hanover bars on larger phase errors.

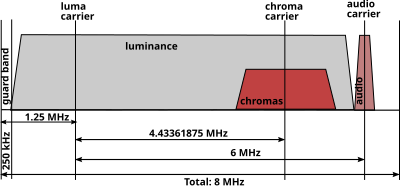

In any case, NTSC, PAL, and SECAM all have chrominance bandwidth (horizontal colour detail) reduced greatly compared to the luma signal.

Many countries have turned off analogue transmissions, so the following does not apply anymore, except for using devices which output RF signals, such as video recorders.

[19] On the studio production level, standard PAL cameras and equipment were used, with video signals then transcoded to PAL-N for broadcast.

Likewise, any tape recorded in Argentina, Paraguay or Uruguay off a PAL-N TV broadcast can be sent to anyone in European countries that use PAL (and Australia/New Zealand, etc.)

This will also play back successfully in Russia and other SECAM countries, as the USSR mandated PAL compatibility in 1985—this has proved to be very convenient for video collectors.

A few DVD players sold in Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay also allow a signal output of NTSC-M, PAL, or PAL-N.

In that case, a PAL disc (imported from Europe) can be played back on a PAL-N TV because there are no field/line conversions, quality is generally excellent.

Video recorders like Panasonic NV-W1E (AG-W1 for the US), AG-W2, AG-W3, NV-J700AM, Aiwa HV-M110S, HV-M1U, Samsung SV-4000W and SV-7000W feature a digital TV system conversion circuitry.

This maintains the runtime of the film and preserves the original audio, but may cause worse interlacing artefacts during fast motion.

In addition, the increased resolution of PAL was often not utilised at all during conversion, creating a pseudo-letterbox effect with borders on the top and bottom of the screen, looking similar to 14:9 letterbox.

The gameplay of many games with an emphasis on speed, such as the original Sonic the Hedgehog for the Sega Genesis (Mega Drive), suffered in their PAL incarnations.

QAM is not required, and frequency modulation of the subcarrier is used instead for additional robustness (sequential transmission of U and V was to be reused much later in Europe's last "analog" video systems: the MAC standards).

One serious drawback for studio work is that the addition of two SECAM signals does not yield valid colour information, due to its use of frequency modulation.

To compete with it at the same level, it had to make use of the main ideas outlined above, and as a consequence PAL had to pay licence fees to SECAM.

But the FM nature of colour in SECAM allows for a cheaper trick: division by 4 of the subcarrier frequency (and multiplication on replay).

Another difference in colour management is related to the proximity of successive tracks on the tape, which is a cause for chroma crosstalk in PAL.

The media's flexible and transmissive material allowed for direct access to both sides without flipping the disc, a concept that reappeared in multi-layered DVDs about fifteen years later.