pH indicator

Since most naturally occurring organic compounds are weak electrolytes, such as carboxylic acids and amines, pH indicators find many applications in biology and analytical chemistry.

For pH indicators that are weak electrolytes, the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation can be written as: The equations, derived from the acidity constant and basicity constant, states that when pH equals the pKa or pKb value of the indicator, both species are present in a 1:1 ratio.

This pH range varies between indicators, but as a rule of thumb, it falls between the pKa or pKb value plus or minus one.

Conversely, if a 10-fold excess of the acid occurs with respect to the base, the ratio is 1:10 and the pH is pKa − 1 or pKb − 1.

pH indicators are frequently employed in titrations in analytical chemistry and biology to determine the extent of a chemical reaction.

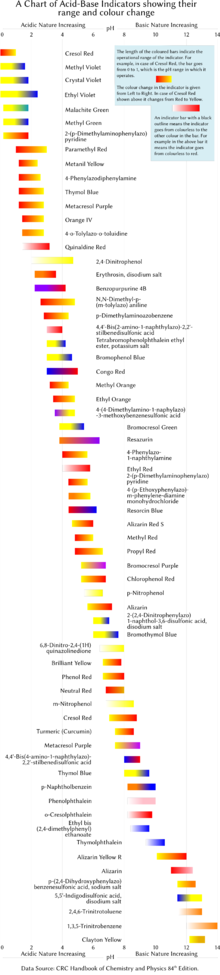

Sometimes, a blend of different indicators is used to achieve several smooth color changes over a wide range of pH values.

Indicators usually exhibit intermediate colors at pH values inside the listed transition range.

The molar absorbances, εHA and εA− of the two species HA and A− at wavelengths λx and λy must also have been determined by previous experiment.

Once solved, the pH is obtained as If measurements are made at more than two wavelengths, the concentrations [HA] and [A−] can be calculated by linear least squares.

The observed spectrum (green) is the sum of the spectra of HA (gold) and of A− (blue), weighted for the concentration of the two species.

In acid-base titrations, an unfitting pH indicator may induce a color change in the indicator-containing solution before or after the actual equivalence point.

Extracting anthocyanins from household plants, especially red cabbage, to form a crude pH indicator is a popular introductory chemistry demonstration.

Litmus, used by alchemists in the Middle Ages and still readily available, is a naturally occurring pH indicator made from a mixture of lichen species, particularly Roccella tinctoria.