Paavo Nurmi

Nurmi set 22 official world records at distances between 1,500 metres and 20 kilometres, and won nine gold and three silver medals in his 12 events in the Summer Olympic Games.

Nurmi started to flourish during his military service, setting Finnish records in athletics en route to his international debut at the 1920 Summer Olympics.

Seemingly unaffected by the Paris heat wave, Nurmi won all his races and returned home with five gold medals,[3] although he was frustrated that Finnish officials had refused to enter him for the 10,000 m. Struggling with injuries and motivation issues after his exhaustive U.S. tour in 1925, Nurmi found his long-time rivals compatriot Ville Ritola and Sweden's Edvin Wide ever more serious challengers.

[7] At 15, Nurmi rekindled his interest in athletics after being inspired by the performances of Hannes Kolehmainen, who was said to "have run Finland onto the map of the world" at the 1912 Summer Olympics.

[9] He took his first medal by finishing second to Frenchman Joseph Guillemot in the 5000 m. This would remain the only time that Nurmi lost to a non-Finnish runner in the Olympics.

[8] He went on to win gold medals in his other three events: the 10,000 m, sprinting past Guillemot on the final curve and improving his personal best by over a minute,[12] the cross country race, beating Sweden's Eric Backman, and the cross country team event where he helped Heikki Liimatainen and Teodor Koskenniemi defeat the British and Swedish teams.

[16] On 19 June, Nurmi tried out the 1924 Olympic schedule at the Eläintarha Stadium in Helsinki by running the 1500 m and the 5000 m inside an hour, setting new world records for both distances.

[18] His only challenger, Ray Watson of the United States, gave up before the last lap and Nurmi was able to slow down and coast to victory ahead of Willy Schärer, H. B. Stallard and Douglas Lowe,[18] still breaking the Olympic record by three seconds.

[18] Nurmi had won five gold medals in five events, but he left the Games embittered as the Finnish officials had allocated races between their star runners and prevented him from defending his title in the 10,000 m, the distance that was dearest to him.

[31] The tour made Nurmi extremely popular in the United States, and the Finn agreed to meet President Calvin Coolidge at the White House.

[40] At the 1928 Olympic trials, Nurmi was left third in the 1500 m by eventual gold and bronze medalists Harri Larva and Eino Purje, and he decided to concentrate on the longer distances.

[43] On the final lap, he sprinted clear of the others and finished nine seconds behind the world-record setting Loukola; Nurmi's time also bettered the previous record.

[49] Nurmi planned to compete only in the 10,000 m and the marathon in the 1932 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, stating that he "won't enter the 5000 metres for Finland has at least three excellent men for that event.

[59] Less than three days before the 10,000 m, a special commission of the IAAF, consisting of the same seven members that had suspended Nurmi, rejected the Finn's entries and barred him from competing in Los Angeles.

[62] [The rules for disqualification of an athlete were made only after the Olympics at the Congress (General Assembly) of the International Sports Federation (IAAF), where Edström and Bo Ekelund, secretary of the council, represented Sweden.

][63][64] Edström stated that the full congress of the IAAF, which was scheduled to start the next day, could not reinstate Nurmi for the Olympics but merely review the phases and political angles related to the case.

[60] The AP called this "one of the slickest political maneuvers in international athletic history", and wrote that the Games would now be "like Hamlet without the celebrated Dane in the cast.

[65] The statements were produced by Karl Ritter von Halt, after Edström had sent him increasingly threatening letters warning that if evidence against Nurmi were not provided he would be "unfortunately obliged to take stringent action against the German Athletics Association.

[69] Edström's right-hand man Bo Ekelund, secretary general of the IAAF and head of the Swedish Athletics Federation, approached the Finnish officials and stated that he might be able to arrange for Nurmi to participate in the marathon outside the competition.

[71] Finns charged that the Swedish officials had used devious tricks in their campaign against Nurmi's amateur status,[72] and ceased all athletic relations with Sweden.

[88] In February 1940, during the Winter War between Finland and the Soviet Union, Nurmi returned to the United States with his protégé Taisto Mäki, who had become the first man to run the 10,000 m under 30 minutes, to raise funds and rally support to the Finnish cause.

[91] Nurmi left for Finland in late April,[92] and later served in the Continuation War in a delivery company and as a trainer in the military staff.

When the national teams, assembled in formation on the infield, saw the flowing figure of Nurmi, they broke ranks like excited schoolchildren, dashing toward the edge of the track.

[100] Nurmi lived to see the renaissance of Finnish running in the 1970s, led by athletes such as the 1972 Olympic gold medalists Lasse Virén and Pekka Vasala.

[9] Although he accepted an invitation from President Lyndon B. Johnson to revisit the White House in 1964,[101] Nurmi lived a very secluded life until the late 1960s when he began granting some press interviews.

[9] Acclaimed the biggest sporting figure in the world at his peak,[110] Nurmi was averse to publicity and the media,[9] stating later on his 75th birthday, "[W]orldly fame and reputation are worth less than a rotten lingonberry.

"[111] Some contemporary Finns nicknamed him Suuri vaikenija (The Great Silent One),[112] and Ron Clarke noted that Nurmi's persona remained a mystery even to Finnish runners and journalists: "Even to them, he was never quite real.

"[120] Phil Cousineau noted that "his own innovation — the tactic of pacing himself with a stopwatch — both inspired and troubled people in an era when the robot was becoming symbolic of the modern soulless human being.

[134] In a widely publicized prank by the students of the Helsinki University of Technology, a miniature copy of the statue was discovered from the 300-year-old wreck of the Swedish war ship Vasa when it was lifted from the bottom of the sea in 1961.

[141] The other revised bills honored architect Alvar Aalto, composer Jean Sibelius, Enlightenment thinker Anders Chydenius and author Elias Lönnrot, respectively.

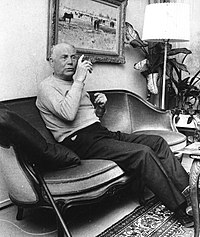

his family in 1924