Pacific Guano Company

After a time, it was suggested that the guano might be improved by the admixture of refuse fish, and that the ammonia lost by exposure to the weather might thus be replaced.

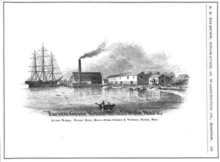

[1] In 1863, the works were removed to Woods Hole, Barnstable County, Massachusetts, with the intention of capturing the fish needed, and after extracting the oil, applying the pumice to the manufacture of guano.

That at Woods Hole, which was considered to be the representative establishment, was situated on Long Neck peninsula (now known as Penzance Point),[5] about 0.5 miles (0.80 km) northwest of the village.

The factory buildings were very extensive, covering nearly 2 acres (0.81 ha) of land, and were used exclusively in the manufacture of the guano, and sulphuric acid used in its development, and for storing the raw materials.

The ingredients of manufacture were few and simple, viz: fish-scrap, mineral phosphate of lime, sulphuric acid, and incidentally kainite, and sometimes common salt.

The company owned Swan Island, situated in the Caribbean Sea, about 290 miles (470 km) off Jamaica, and the phosphate of lime was obtained from that point until 1866 or 1867, when the reopening of the south gave access to the Charleston beds.

The company used a considerable quantity of the rock from Navassa, a small island lying between Cuba and Santo Domingo, a reddish deposit, rich in phosphate of lime.

[1] In the early days of the business, the sulphuric acid was brought from Waltham, Massachusetts, and New Haven, Connecticut, in carboys, but from 1866, it was manufactured in Woods Holl at a large saving of expense.

[1] The scrap having been stored in one wing of the factory, the ground phosphate in another, the sulphuric acid having been forced into a reservoir near by, by pneumatic pressure, the process of mixing was easily carried on.

This process was laborious and very expensive, and various machines were devised, but they proved failures because the materials caked, clogging the wheels and knives in a very short time.

Residue of this kind was subjected to the action of the Carr's disintegrator, which consisted of two wheels revolving in opposite directions at the rate of 600 revolutions to the minute.

[1] The offensive odor of the factories rendered them disagreeable to persons residing in the neighborhood, and legal measures were taken in one or two instances to prevent the manufacturers from carrying on their business.

In Connecticut vs. Enoch Coe, of Brooklyn, New York, on May 5, 1871, at the session of the United States circuit court in New Haven, Judge Lewis Bartholomew Woodruff granted an injunction to restrain the defendant from manufacturing manure from fish at his works in Norwalk Harbor, on the ground that the same created a nuisance.

People interested in building up Woods Holl as a watering place once agitated legal measures to compel a removal of the works, but the general sentiment of the town of Falmouth, Massachusetts in which the company paid heavy taxes, and specially of the many villagers of Woods Hole who earn their living in the works, prevented any results.