Niccolò Paganini

Son of a ship chandler from Genoa, Paganini showed great gifts for music from an early age and studied under Alessandro Rolla, Ferdinando Paer and Gasparo Ghiretti.

From 1809 on he returned to touring and achieved continental fame in the subsequent two and a half decades, developing a reputation for his technical brilliance and showmanship, as well as his extravagant, philandering lifestyle.

Paganini ended his concert career in 1834 amid declining health, and the failure of his Paris casino left him in financial ruin.

[1]: 11 Antonio Paganini was an unsuccessful ship chandler,[2] but he managed to supplement his income by working as a musician and by selling mandolins.

The young Paganini studied under various local violinists, including Giovanni Servetto and Giacomo Costa, but his progress quickly outpaced their abilities.

Paganini became a violinist for the Baciocchi court, while giving private lessons to Elisa's husband, Felice for ten years.

[5][6] His fame spread across Europe with a concert tour that started in Vienna in August 1828, stopping in every major European city in Germany, Poland, and Bohemia until February 1831 in Strasbourg.

In addition to his own compositions, theme and variations being the most popular, Paganini also performed modified versions of works (primarily concertos) written by his early contemporaries, such as Rodolphe Kreutzer and Giovanni Battista Viotti.

Paganini's travels also brought him into contact with eminent guitar virtuosi of the day, including Ferdinando Carulli in Paris and Mauro Giuliani in Vienna.

Paganini was diagnosed with syphilis as early as 1822, and his remedy, which included mercury and opium, came with serious physical and psychological side effects.

Contrary to popular beliefs involving his wishing to keep his music and techniques secret, Paganini devoted his time to the publication of his compositions and violin methods.

In Paris, he befriended the 11-year-old Polish virtuoso Apollinaire de Kontski, giving him some lessons and a signed testimonial.

Its immediate failure left him in financial ruin, and he auctioned off his personal effects, including his musical instruments, to recoup his losses.

[12] Though having no shortage of romantic conquests, Paganini was seriously involved with a singer named Antonia Bianchi from Como, whom he met in Milan in 1813.

Despite his alleged lack of interest in Harold, Paganini often referred to Berlioz as the resurrection of Beethoven and, towards the end of his life, he gave large sums to the composer.

While Paganini was still a teenager in Livorno, a wealthy businessman named Livron lent him a violin, made by the master luthier Giuseppe Guarneri, for a concert.

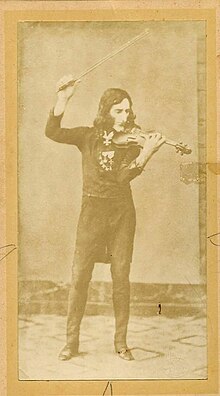

He had exceptionally long fingers and was capable of playing three octaves across four strings in a hand span, an extraordinary feat even by today's standards.

[20] Paganini composed his own works to play exclusively in his concerts, all of which profoundly influenced the evolution of violin technique.

Many of his variations, including Le Streghe, The Carnival of Venice, and Nel cor più non-mi sento, were composed, or at least first performed, before his European concert tour.

Generally speaking, Paganini's compositions were technically imaginative, and the timbre of the instrument was greatly expanded as a result of these works.

One such composition was titled Il Fandango Spanolo (The Spanish Dance), which featured a series of humorous imitations of farm animals.

[23] Yehudi Menuhin, on the other hand, suggested that this might have been the result of Paganini's reliance on the guitar (in lieu of the piano) as an aid in composition.

In this, his style is consistent with that of other Italian composers such as Giovanni Paisiello, Gioachino Rossini, and Gaetano Donizetti, who were influenced by the guitar-song milieu of Naples during this period.

24) have inspired many composers, including Franz Liszt, Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Boris Blacher, Andrew Lloyd Webber, George Rochberg, and Witold Lutosławski, all of whom wrote variations on these works.

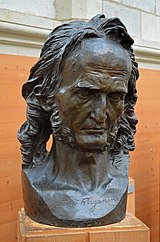

[28] Although no photographs of Paganini are known to exist, in 1900 Italian violin maker Giuseppe Fiorini forged the now famous fake daguerreotype of the celebrated violinist.

[29] So well in fact, that even the great classical author and conversationalist Arthur M. Abell was led to believe it to be true, reprinting the image in the 22 January 1901 issue of the Musical Courier.

One memorable scene shows Paganini's adversaries sabotaging his violin before a high-profile performance, causing all strings but one to break during the concert.

In Don Nigro's satirical comedy play Paganini (1995), the great violinist seeks vainly for his salvation, claiming that he unknowingly sold his soul to the Devil.

In the end, Paganini's salvation—administered by a god-like Clockmaker—turns out to be imprisonment in a large bottle where he plays his music for the amusement of the public through all eternity.

The musical Cross Road, premiered 2022 and revived 2024, features Niccolo Paganini as a main character, played by Hiroki Aiba (2022 and 2024), Kenta Mizue (2022), and Kento Kinouchi (2024).