Pair bond

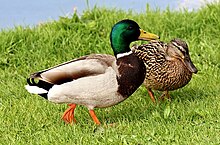

According to evolutionary psychologists David P. Barash and Judith Lipton, from their 2001 book The Myth of Monogamy, there are several varieties of pair bonds:[2] Close to ninety percent[3] of known avian species are monogamous, compared to five percent of known mammalian species.

The majority of monogamous avians form long-term pair bonds which typically result in seasonal mating: these species breed with a single partner, raise their young, and then pair up with a new mate to repeat the cycle during the next season.

Some avians such as swans, bald eagles, California condors, and the Atlantic Puffin are not only monogamous, but also form lifelong pair bonds.

Before this time, as well as after—that is, when her eggs are not ripe, and again after his genes are safely tucked away inside the shells—he goes seeking extra-pair copulations with the mates of other males…who, of course, are busy with defensive mate-guarding of their own.

Peptide arginine vasopressin (AVP), dopamine, and oxytocin act in this region to coordinate rewarding activities such as mating, and regulate selective affiliation.

These species-specific differences have shown to correlate with social behaviors, and in monogamous prairie voles are important for facilitation of pair bonding.

[15] Like in other vertebrates, pair bonds are created by a combination of social interaction and biological factors including neurotransmitters like oxytocin, vasopressin, and dopamine.