Palace of Aachen

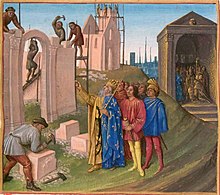

The Palace of Aachen was a group of buildings with residential, political, and religious purposes chosen by Charlemagne to be the center of power of the Carolingian Empire.

In ancient times, the Romans chose the site of Aachen for its thermal springs and its forward position towards Germania.

Clovis made Paris the capital of the Frankish Kingdom, and Aachen Palace was abandoned until the advent of the Carolingian dynasty.

Around 765, Pepin the Short had a palace erected over the remains of the old Roman building; he had the thermae restored and removed its pagan idols.

[4] Since his advent as King of the Franks, Charlemagne had led numerous military expeditions that had both filled his treasury and enlarged his realm, most notably towards the East.

[5] Aachen's geographic location was a decisive factor in Charlemagne's choice: the site was situated in the Carolingian heartlands of Austrasia, the cradle of his family, East of the Meuse river, at a crossroads of land roads and on a tributary of the Rur, called the Wurm.

From then, Charlemagne left the administration of the Southern regions to his son Louis, named King of Aquitaine,[6] which enabled him to reside in the North.

[7] Charlemagne also considered other advantages of the place: surrounded with forest abounding in game, he intended to abandon himself to hunting in the area.

The scholars of the Carolingian era presented Charlemagne as the "New Constantine"; in this context, he needed a capital and a palace worthy of the name.

This occasion gathered the highest officials in the Carolingian Empire, dignitaries and the hierarchy of the power: counts, vassals of the king, bishops and abbots.

The structure was made of brick, and the shape was that of a civil basilica with three apses: the largest one (17,2 m),[15] located to the West, was dedicated to the king and his suite.

Several buildings used by the clerics of the chapel were arranged in the shape of a latin cross: a curia in the East, offices in the North and South, and a projecting part (Westbau[21]) and an atrium with exedrae in the West.

The king sat on a throne made of white marble plates, in the West of the second floor, surrounded by his closer courtiers.

Thus he had a view on the three altars: that of the Savior right in front of him, that of the Virgin Mary on the first floor and that of Saint Peter in the far end of the Western choir.

Charlemagne wanted his chapel to be magnificently decorated, so he had massive bronze doors made in a foundry near Aachen.

[...] He provided it with a great number of sacred vessels of gold and silver and with such a quantity of clerical robes that not even the doorkeepers who fill the humblest office in the church were obliged to wear their everyday clothes when in the exercise of their duties.

[27] The outer perimeter of the cupola measures exactly 144 Carolingian feet whereas that of the heavenly Jerusalem, ideal city drawn by angels, is of 144 cubits.

[29] The treasury gathered gifts brought by the kingdom's important people during the general assemblies or by foreign envoys.

The king dispensed justice in this place, although affairs in which important people were involved were handled in the aula regia.

The Palace school provided education to the ruler's children and the "nourished ones" (nutriti in Latin), aristocrat sons that were to serve the king.

Outside of the palace complex were also a gynaeceum, barracks, a hospice,[17] a hunting park and a menagerie in which lived the elephant Abul-Abbas, given by Baghdad Caliph Harun al-Rashid.

The chapel follows models from ancient Rome: grids exhibit antique decorations (acanthus[36]) and columns are topped by Corinthian capitals.

Although many references to Roman and Byzantine models are visible in Aachen's buildings, Odo of Metz expressed his talent for Frankish architect and brought undeniably different elements.

Charlemagne's palace was thus more than a copy of Classical and Byzantine models: it was rather a synthesis of various influences, as a reflection of the Carolingian Empire.

Charlemagne himself wanted to influence religious matters through his reforms and the numerous ecumenical council and synods held in Aachen.

[40] The Palatine Chapel of Aachen seems to have been imitated by several other buildings of the same kind: The octagonal oratory of Germigny-des-Prés, built in the early 9th century for Theodulf of Orléans seems to have been directly related.

The influence of Aachen's chapel is also found in Compiègne[41] and in other German religious buildings (such as the Abbey church of Essen).

Afterwards, and until the 16th century, all the German Emperors were crowned firstly in Aachen and then in Rome, which highlights the attachment to Charlemagne's political legacy.

In the 12th century, Frederick Barbarossa placed the body of the Carolingian Emperor into a reliquary and interceded with the Pope for his canonization; the relics were scattered across the empire.

Before choosing Notre-Dame de Paris, Napoleon I had considered for a time holding his Imperial Coronation in Aachen.