Palaeologan Renaissance

Craftsmen worked with less rare and expensive materials than before— an example is the use of steatite in sculptures that would formerly have been made of ivory— and sponsorship came from a multitude of private patrons instead of being dominated by the emperor.

[17] The Palaeologan period was also the first in which Byzantine painters regularly signed their works; it is not clear why this custom developed, since innovation and stylistic individuality continued to be discouraged in Orthodox art.

It was located in a hospital and attached to the monastery of St. John Prodrome, whose rich library had at its disposal numerous teachers including Georges Chrysococè and Cardinal Bessarion, who later settled in Italy.

Also during the reign of Manuel II, the scholar Demetrios Kydones wrote several texts such as the Discourses and Dialogues on the relationship between Christianity and Islam, on politics and on civil subjects such as marriage and education.

Among these were the judge and historian George Pachymeres (1242 – c. 1310), and four great philological scholars of the time of Andronikos II: Thomas Magistros, Demetrius Triclinios, Manuel Moschopoulos, and the theologian Maximus Planudes (c. 1255/1260 – c. 1305/1310).

[30] Gemistos Plethon was exiled by Manuel II to the Despotate of Morea, an important intellectual center; his lectures there revived Platonic thought in Western Europe.

[31] Cyril Mango describes "a distinctive new style" in Palaeologan painting, "marked by a multiplication of figures and scenes, by a new interest in perspective (however strangely rendered), and by a return to much earlier models such as illuminated manuscripts of the 10th century".

[33] Contemporary trends in church painting favored intricate narrative cycles, both in fresco and in sequences of icons;[28] to serve this need, the traditional large, portrait-style holy images were partially superseded by landscape scenes with comparatively small figures, often depicted in motion.

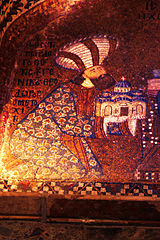

[37] In the mosaics and frescos of Chora Church, as well as certain other works from Constantinople, foreshortening is used for narrative purposes, making buildings lean toward the intended focus of the viewer's attention.

[33] Kurt Weitzmann speaks of "over-elongated figures", placed in "swaying poses" and wearing draperies which "bulge slightly, giving the impression of detachment from the frail bodies underneath".

[39] Hard, geometrically patterned highlights are used to give figures the appearance of volume, albeit without interest in depicting realistic anatomical construction or a coherent light source.

[35] As part of a general increase of paintings in late Byzantine church interiors, more panels were added and the templon evolved into the iconostasis, "a solid wall of icons... between the worshipper and the mystery of the Christian service".

[34] By the 12th century, usage in this important and highly visible context had made panel paintings into a more prestigious art form, suitable for wealthy patrons to commission.

Even quite large icons, four to six feet high or more and depicting figures greater than life size, began to be executed in tempera, rather than in the traditional media of fresco or mosaic.

[46] This work gives its figures a gentle and compassionate aspect, and uses tiny tesserae to achieve fine modeling on their faces, evocative of painting; despite its monumental size, it seems intended to possess the personality of an icon.

This compositional motif, evidently dictated by "the preferences of high ecclesiastical circles in the Capital",[46] required coordination between the churches' builders and iconographic planners, to ensure that a dome had the right number of flutes to accommodate the intended group of figures.

Their varying demographics and resources produced distinctive regional styles of architecture: Epirus built grandiose monuments incorporating much spolia from Roman ruins, and the Despotate of the Morea, held by the Crusaders until 1262, showed a pronounced Western influence.

More attention was paid to the external appearance of the domes on their roofs, and the walls were "enlivened plastically by means of niches, arcades, corbels, and strings of dentils− that is, elements that create a play of light and shadow".

[55] Two–dimensional artworks from the Palaeologan period— including the aforementioned donor portraits— show people dressed in elaborate costumes,[56] giving evidence for personal adornments which have otherwise disappeared.

[57] The same secondary evidence leads David Talbot Rice to assert that the Byzantine silk industry survived into this period, and continued to produce garments decorated with the traditional tapestry technique.