Paleoart

While paleoart is typically defined as being scientifically informed, it is often the basis of depictions of prehistoric animals in popular culture, which in turn influences public perception of and fuels interest in these organisms.

[8] Mark Hallett, who coined the term "paleoart" in 1987, stressed the importance of the cooperative effort between artists, paleontologists and other specialists in gaining access to information for generating accurate, realistic restorations of extinct animals and their environments.

[25] Skeletal reference—not just the bones of vertebrate animals, but including any fossilized structures of soft tissue–such as lignified plant tissue and coral framework—is crucial for understanding the proportions, size and appearance of extinct organisms.

Given that many fossil specimens are known from fragmentary material, an understanding of the organisms' ontogeny, functional morphology, and phylogeny may be required to create scientifically-rigorous paleoart by filling in restorative gaps parsimoniously.

Therefore, a variety of factors other than science can influence paleontological illustrators, including the expectations of editors, curators, and commissioners, as well as long-standing assumptions about the nature of ancient organisms that may be repeated through generations of paleoart, regardless of accuracy.

Other scholars have suggested that ancient fossils inspired Grecian depictions of griffins, with the mythical chimera of lion and bird anatomy superficially resembling the beak, horns and quadrupedal body plan of the dinosaur Protoceratops.

[40] The German textbook Mundus Subterraneus, authored by scholar Athanasius Kircher in 1678, features a number of illustrations of giant humans and dragons that may have been informed by fossil finds of the day, many of which came from quarries and caves.

These artworks are of uncertain origin and may have been created by Otto von Guericke, the German naturalist who first described the "unicorn" remains in his writings, or Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, the author who published the image posthumously in 1749.

These ink drawings were relatively quick sketches accompanying his notes on the fossil and were likely never intended for publication, and their existence was only recently uncovered from correspondence between the artist and the French anatomist Baron Georges Cuvier.

[46] Similarly, private sketches of mammoth fossils drafted by Yakutsk merchant Roman Boltunov in 1805 were likely never intended for scientific publication, but their function—to communicate the life appearance of an animal whose tusks he had found in Siberia and was hoping to sell—nevertheless establishes it one of the first examples of paleoart by today's definition.

Several authors have remarked on De la Beche's apparent interest in fossilized feces, speculating that even the shape of the cave in this cartoon is reminiscent of the interior of an enormous digestive tract.

For example, a book by French scientist Louis Figuier titled La Terre Avant le Deluge, published in 1863, was the first to feature a series of works of paleoart documenting life through time.

[62] As the western frontier was further opened up in the latter half of the nineteenth century, the rapidly increasing pace of dinosaur discoveries in the bone-rich badlands of the American Midwest and the Canadian wilderness brought with it a renewed interest in artistic reconstructions of paleontological findings.

His birth three years after Charles Darwin's publication of the influential Descent of Man, along with the "Bone Wars" between rival American paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Marsh raging during his childhood, had poised Knight for rich early experiences in developing an interest in reconstructing prehistoric animals.

[64] Knight's foray into paleoart can be traced to a commission ordered by Jacob Wortman in 1894 of a painting of an extinct hoofed animal, Elotherium, to accompany its fossil display at the American Museum of Natural History.

[66] Biologist Stephen Jay Gould later remarked on the depth and breadth of influence that Knight's paleoart had on shaping public perception of extinct animals, even without having published original research in the field.

Gould described Knight's contribution to scientific understanding in his 1989 book Wonderful Life: "Not since the Lord himself showed his stuff to Ezekiel in the valley of dry bones had anyone shown such grace and skill in the reconstruction of animals from disarticulated skeletons.

Zallinger, a Russia-born American painter, began working for the Yale Peabody Museum illustrating marine algae around the time that the United States entered World War II.

[75] Some authors have remarked on a darker, more sinister feel to his paleoart than that of his contemporaries, speculating that this style was informed by Burian's experience producing artwork in his native Czechoslovakia during World War II and, afterwards, under Soviet control.

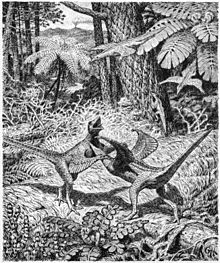

[79] One of Harder's contemporaries, Danish paleontologist Gerhard Heilmann, produced a large number of sketches and ink drawings related to Archaeopteryx and avian evolution, culminating in his lavishly illustrated and controversial treatise The Origin of Birds, published in 1926.

[83] American scientist-artist Gregory Paul, working originally as Bakker's student in the 1970s, became one of the leading illustrators of prehistoric reptiles in the 1980s and has been described by some authors as the paleoartist who may "define modern paleoart more than any other".

[84] Paul is notable for his 'rigorous' approach to paleoartistic restorations, including his multi-view skeletal reconstructions, evidence-driven studies of musculature and soft tissue, and his attention to biomechanics to ensure realistic poses and gaits of his artistic subjects.

[87][88] Many of these artists developed unique and lucrative stylistic niches without sacrificing their rigorous approach, such as Douglas Henderson's detailed and atmospheric landscapes, and Luis Rey's brightly-colored, "extreme" depictions.

[89] The "Renaissance" movement so revolutionized paleoart that even the last works of Burian, a master of the "classic" age, were thought to be influenced by the newfangled preference for active, dynamic, exciting depictions of dinosaurs.

Precision in anatomy and artistic reconstruction was aided by an increasingly detailed and sophisticated understanding of these extinct animals through new discoveries and interpretations that pushed paleoart into more objective territory with respect to accuracy.

Gregory Paul's high-fidelity archosaur skeletal reconstructions provided a basis for ushering in the modern age of paleoart, which is perhaps best characterized by adding speculative flair to the rigorous, anatomically-conscious approach popularized by the Dinosaur Renaissance.

[96] These ideas were formalized in a 2012 book by paleoartists John Conway and Nemo Ramjet (also known as C.M Kosemen), along with paleontologist Darren Naish, called All Yesterdays: Unique and Speculative Views of Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Animals.

[99] Despite the importance of the "All Yesterdays" movement in hindsight, the book itself argued that the modern conceptualization of paleoart was based on anatomically rigorous restorations that came alongside and subsequent to Paul, including those who experimented with these principles outside of archosaurs.

[102] In a 2014 paper, Mark Witton, Darren Naish, and John Conway outlined the historical significance of paleoart, and criticized the over-reliance on clichés and the "culture of copying" they saw to be problematic in the field at the time.

[110] Starting in the 2010s, paleoart and its public perception have also been the exclusive focus of research articles that (e.g.) attempt to apply empirical methods to understand its role in society[111] or communicate its evolution over time to other scientists.