Palladium (protective image)

The word is a generalization from the name of the original Trojan Palladium, a wooden statue (xoanon) of Pallas Athena that Odysseus and Diomedes stole from the citadel of Troy.

It was a wooden image of Pallas (whom the Greeks identified with Athena and the Romans with Minerva) said to have fallen from heaven in answer to the prayer of Ilus, the founder of Troy.

The cult image of the Poliás was a wooden effigy, often referred to as the "xóanon diipetés" (the "carving that fell from heaven"), made of olive wood and housed in the east-facing wing of the Erechtheum temple in the classical era.

Its presence was last mentioned by the Church Father Tertullian (Apologeticus 16.6), who, in the late 2nd century AD, described it derisively as being nothing but "a rough stake, a shapeless piece of wood" (Latin original: "[] Pallas Attica [] quae sine effigie rudi palo et informi ligno prostat?").

In Celtic Christianity, palladia were more often relics that were typically possessions of a saint, such as books, bells, belts and croziers, all housed in reliquaries.

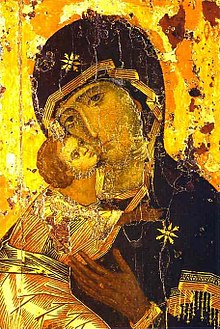

The Byzantine palladia, which first appear in the late 6th century, cannot be said to have had a very successful track record, as apart from Constantinople most major cities in Egypt, Syria and later Anatolia fell to Muslim attacks.

According to Iconoclast sources an officer called Constantine, defending Nicaea against an Arab siege in 727, smashed an icon of the Virgin, and this saved the city.