London Stone

[1] It is an irregular block of oolitic limestone measuring 53 × 43 × 30 cm (21 × 17 × 12"), the remnant of a once much larger object that had stood for many centuries on the south side of the street.

There has been interest and speculation about it since the medieval period, but modern claims that it was formerly an object of veneration, or has some occult significance, are unsubstantiated.

By the time of Queen Elizabeth I London Stone was not merely a landmark, shown and named on maps, but a visitor attraction in its own right.

[12] In 1608 it was listed in a poem by Samuel Rowlands as one of the "sights" of London (perhaps the first time the word was used in that sense) shown to "an honest Country foole" on a visit to town.

Thus, for example, Thomas Heywood's biography of Queen Elizabeth I, Englands Elizabeth (1631), was, according to its title page, "printed by Iohn Beale, for Phillip Waterhouse; and are to be sold at his shop at St Pauls Head, neere London stone"; and the English Short Title Catalogue lists over 30 books published between 1629 and the 1670s with similar references to London Stone in the imprint.

[15] In 1671 the Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers broke up a batch of substandard spectacles on London Stone: Two and twenty dozen [= 264] of English spectacles, all very badd both in the glasse and frames not fitt to be put on sale ... were found badd and deceitful and by judgement of the Court condemned to be broken, defaced and spoyled both glasse and frame the which judgement was executed accordingly in Canning [Cannon] Street on the remayning parte of London Stone where the same were with a hammer broken in all pieces.

[18] In 1598 John Stow had commented that "if carts do run against it through negligence, the wheels be broken, and the stone itself unshaken",[6] and by 1742 it was considered an obstruction to traffic.

In 1869 the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society arranged for the installation of a protective iron grille and an explanatory inscription in Latin and English on the church wall above it.

The stone and its surround, including the iron grille, were designated a Grade II* listed structure on 5 June 1972.

[1] In the early 21st century the office building was scheduled for redevelopment, and in October 2011 the then landowners proposed to move the stone to a new location further to the west.

Objections were raised by, among others, the Victorian Society and English Heritage, and the proposal was rejected by the City of London Corporation.

In 1450 Jack Cade, leader of the rebellion against the corrupt government of Henry VI, struck it with his sword and claimed to be Lord of London.

In 1742, London Stone was moved to the north side of the street and eventually set in an alcove in the wall of St Swithin's church on this site.

The church was bombed in the Second World War and demolished in 1961–1962, and London Stone was incorporated into a new office building on the site.

The Short English Metrical Chronicle, an anonymous history of England in verse composed in about the 1330s, which survives in several variant recensions (including one in the so-called Auchinleck manuscript), includes the statement that "Brut sett Londen ston" – that is to say, that Brutus of Troy, the legendary founder of London, set up London Stone.

[33] Although this suggestion is now generally dismissed, it was revived in 1914 by Elizabeth Gordon in an unorthodox book on the archaeology of prehistoric London.

In an earlier book, Morgan had claimed that the legendary Brutus was a historical figure; London Stone, he wrote, had been the plinth on which the original Trojan Palladium had stood, and was brought to Britain by Brutus and set up as the altar stone of the Temple of Diana in his new capital city of Trinovantum or "New Troy" (i.e.

[42] Later, folklorist Lewis Spence combined this theory with Morgan's story of the "Stone of Brutus" to speculate about the pre-Roman origins of London in a 1937.

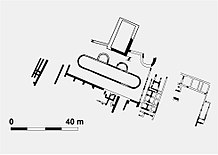

It has further been suggested – originally by the archaeologist Peter Marsden, who excavated there from 1961–1972 – that the Stone may have formed part of its main entrance or gate.

The first claims that John Dee – astrologer, occultist and adviser to Queen Elizabeth I – "was fascinated by the supposed powers of the London Stone and lived close to it for a while" and may have chipped pieces off it for alchemical experiments; the second that a legend identifies it as the stone from which King Arthur pulled the sword to reveal that he was rightful king.

Some writers have argued that this fictional episode proves that London Stone was a traditional place for making official proclamations.

[43][56] The Jack Cade episode was dramatised in William Shakespeare's Henry VI, Part 2 (act 4, scene 6), first performed c. 1591–2.

Thus in Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion, his long illustrated poem on engraved plates begun in 1804, London Stone is a Druidic altar, the site of bloody sacrifices.