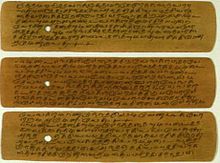

Palm-leaf manuscript

[2] One of the oldest surviving palm leaf manuscripts of a complete treatise is a Sanskrit Shaivism text from the 9th century, discovered in Nepal, and now preserved at the Cambridge University Library.

Such palm leaf texts typically had a lifespan of between a few decades and roughly 600 years before they started to rot due to moisture, insect activity, mould, and fragility.

[8] Archaeological and epigraphical evidence indicates the existence of libraries called Sarasvati-bhandara, dated possibly to the early 12th century and employing librarians, attached to Hindu temples.

With the spread of Indian culture to Southeast Asian countries like as Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, Laos, and the Philippines, these nations also became home to large collections.

[14] Palm-leaf manuscripts or sleuk rith as they are known in the Khmer language, can be found in Cambodia since Angkorian times as can be seen from at least one bas-relief on the walls of Angkor Wat.

While they were of major importance until the 20th century, French archeologist Olivier de Bernon estimated that about 90% of all the sleuk rith were lost in the turmoil of the Cambodian Civil War while new supports such as codex books or digital media took over.

[17] In 1997 The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) recognised the Tamil Medical Manuscript Collection as part of the Memory of the World Register.

A very good example of the usage of palm leaf manuscripts to store history is a Tamil grammar book named Tolkāppiyam, written around the 3rd century BCE.

The leaves of the rontal tree have always been used for many purposes, such as for the making of plaited mats, palm sugar wrappers, water scoops, ornaments, ritual tools, and writing material.

Today, the art of writing in rontal still survives in Bali, performed by Balinese Brahmin as a sacred duty to rewrite Hindu texts.

Other palm-leaf manuscripts include Sundanese language works: the Carita Parahyangan, the Sanghyang Siksakandang Karesian, and the Bujangga Manik.

In the pre-colonial era, along with folding-book manuscripts, pesa was a primary medium of transcribing texts, including religious scriptures, and administrative and juridical records.

[21][22] These decorated manuscripts include ornamental motifs and are inscribed with ink on lacquered palm leaves gilded with gold leaf.