Pals battalion

This initiative was in direct contrast to the British military tradition of employing long serving professional soldiers drawn from the gentry (for officers) or the lower classes (for enlisted men).

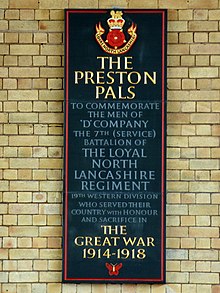

General Sir Henry Rawlinson suggested that men would be more inclined to enlist if they knew that they were going to serve alongside their friends and colleagues.

In September 1914 Kitchener announced that the organizers of locally raised units would have to meet the initial accommodation and other costs involved, until the War Office took over their management.

For members who joined the battalions, the North Eastern Railway gave some offers including; provisions for wives and dependants; to keep men's positions open; to pay their contribution to the Superannuation and Pensions and to provide accommodation for the families who were occupying company houses.

[4] While the majority of pals units were infantry battalions, local initiatives resulted in the raising of forty-eight companies of engineers, forty-two batteries of field artillery and eleven ammunition columns,[2] drawn mainly from groups with common occupational backgrounds.

The practice of drawing recruits from a particular region or group meant that, when a pals battalion suffered heavy casualties, the impact on individual towns, villages, neighbourhoods and communities back in Britain could be immediate and devastating.

As an example, The Sheffield City Battalion (12th York and Lancaster Regiment) lost 495 dead and wounded in one day (1 July 1916) on the Somme and was brought back to strength by October that year only by drafts from diverse areas.

Voluntary local recruitment outside the regular army structure, and although characteristic of the atmosphere of 1914–15, was not repeated in World War II.