Pamir (ship)

Her shipping consortium's inability to finance much-needed repairs or to recruit sufficient sail-trained officers caused severe technical difficulties.

By 1914, she had made eight voyages to Chile, taking between 64 and about 70 days for a one-way trip from Hamburg to Valparaíso or Iquique, the foremost Chilean nitrate ports at the time.

Due to post war conditions, she did not return from Santa Cruz de la Palma to Hamburg until 17 March 1920.

The Italian government was unable to find a deep-water sailing ship crew, so she was laid up near Castellamare in the Gulf of Naples.

She was returned to the Erikson Line on 12 November 1948 at Wellington and sailed to Port Victoria on Spencer Gulf to load Australian grain.

His son Edgar found he could no longer operate her (or Passat) at a profit, owing primarily to changing regulations and union contracts governing employment aboard ships; the standard two-watch system on sailing ships was replaced by the three-watch system in use on motor-ships, requiring more crew.

[6] As she was being towed to Antwerp, German shipowner Heinz Schliewen, who had sailed on her in the late 1920s, bought her (and Passat, thus often erroneously referred to as a sister ship).

[9] For the next five years, the ships continued to sail between Europe and the east coast of South America, but not around Cape Horn.

Although the German public supported the concept as maritime symbols and sources of national pride, the economic realities of the post-war years placed restraints on the operation.

The ships were no longer profitable as freight haulers, and Pamir had increasing technical problems such as leaking decks and serious corrosion.

The consortium was unable to get sufficient increased funding from German governments or contributions from shipping companies or public donations, and thus let both vessels deteriorate.

[10] Records indicate that this was one of the major mistakes implicated in the sinking – she had been held up by a dockworkers' strike, and Diebitsch, under severe pressure to sail, decided to let the trimming (the correct storage of loose cargo so that it does not shift in the hold) be done by his own untrained crew.

Even though testing of the roll period (the time the ship took to right itself after load transfers) showed that she was dangerously unstable, Diebitsch decided to sail.

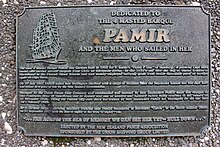

She sent distress signals before capsizing at 13:03 local time, and sinking after drifting keel-up for 30 minutes in the middle of the Atlantic 600 nautical miles (1,100 km; 690 mi) west-southwest of the Azores at position 35°57′N 40°20′W / 35.950°N 40.333°W / 35.950; -40.333.

A nine-day search for survivors was organized by the United States Coast Guard Cutter Absecon, but only four crewmen and two cadets were rescued alive, from two of the lifeboats.

The official documents, including a report by Haselbach during the hours after he was found, say nothing about people screaming when they left the lifeboats.

Pamir's last voyage was the only one in her school ship career during which she made a profit, as the insurance sum of about 2.2 million Deutsche Mark was sufficient to cover the company losses for that year.

While there was no indication that this was the intention of the consortium, which was never legally blamed for the sinking, some later researchers have considered that through its neglect it was at least strongly implicated in the loss.