Panagiotis Kavvadias

He was responsible for the excavation of ancient sites in Greece, including Epidaurus in Argolis and the Acropolis of Athens, as well as archaeological discoveries on his native island of Kephallonia.

[8] Kavvadias also followed a course in epigraphy at the Collège de France in Paris under Paul Foucart,[12][13] a French epigrapher later credited as "the doyen of our field" by the classical archaeologist Salomon Reinach,[14] and also studied in Berlin, London and Rome.

[12] One of his first postings was to the excavations of the French School at Athens on the island of Delos,[17] which had been running since 1873:[18] he was there in 1882, working alongside Reinach, who later wrote that Kavvadias had seemed "full of enthusiasm and ambition".

[26] Kavvadias published the first reports of his excavations in the Government Gazette (Greek: Ἐφημερίς τῆς Κυβερνήσεως), an official publication normally used for laws and royal decrees.

Until 1890, in collaboration with the German archaeologist and architect Georg Kawerau, he excavated or re-excavated almost the whole site, removing nearly all of its remaining post-Classical structures [30] and discovering dozens of works of ancient sculpture, particularly Archaic korai.

[31] After 1890, the work on the Acropolis primarily consisted of restoration, particularly of the Parthenon, Erechtheion and Propylaia, overseen by Nikolaos Balanos, who directed the project largely independently.

[33] He discovered part of a cult group of statues – the work of the Messenian sculptor Damophon – showing Despoina seated on a double throne alongside Demeter, accompanied by Artemis and the Titan Anytos.

[12] The stelae, dating to the late fourth or early third century BCE[41] and sometimes called 'miracle inscriptions',[42] recorded the names of at least twenty individuals and the means by which they were healed – usually miraculous dreams or visions.

[51] Kavvadias's report on his excavations of the Roman-period odeion at the site, which he published in 1900, has been described as "invaluable" for the amount of evidence it preserves, much of which has been lost through later deterioration in the building's condition.

[20] Kavvadias's predecessor as Ephor General of Antiquities, Panagiotis Stamatakis, had planned to complete the excavation of the Acropolis of Athens, but died suddenly in 1884 before work could commence.

[62] In 1889, most of the southern and western part of the Acropolis was cleared of post-Classical remains, as were the interiors of the Parthenon and the Pinakotheke (a chamber in the monument's northern wing)[63] of the Propylaia.

A particularly fruitful area was the so-called 'kore pit', north-west of the Erechtheion, which is the major known source for kore and kouros sculptures of the Archaic period:[31] Kavvadias uncovered somewhere between nine and fourteen korai in the initial excavation alone.

[68] On the northern side of the Acropolis, Kavvadias excavated in 1887 a cave (later identified by the archaeologist Oscar Broneer as part of the Sanctuary of Eros and Aphrodite)[69] in which he found pieces of black-figure pottery, the head of a female sculpture,[70] and what he believed were traces of the secret route described by Pausanias as being used by the arrephoroi during the rite of the Arrhephoria.

[74]Kavvadias made minor excavations in the caves on the northern side of the Acropolis during 1896 and 1897, uncovering one with what he believed to be the remains of an altar,[75] as well as ten marble plaques with inscriptions marking them as a dedication to Apollo, who was identified by the epithet 'under the cliffs' (Greek: ὑπὸ Μάκραις or ὑπ' Ἄκρας).

[32] The Archaeological Service, led by Kavvadias, commissioned the architects Francis Penrose, Josef Durm [de] and Lucien Magne to investigate possible responses, and decided upon a partial reconstruction which would strengthen the damaged parts and replace, where necessary, ancient marble with modern.

[32] They also decided to use, as far as possible, the original building methods (dry-stone masonry held together with metal clamps) in the restoration work, and Kavvadias later wrote in favour of this approach.

[32] Penrose, Durm and Magne formed a supervising committee, but the operational direction was delegated to the 'Committee for the Conservation of the Parthenon', a body which included academics, members of Athens's foreign schools of archaeology, and representatives of the Greek government.

Nikolaos Balanos, Athens's Chief Engineer of Public Works, was invited to join this committee after its formation, and effectively took control of the reconstructions, operating, according to Mallouchou-Tufano, "independently and unchecked".

[83] In 1885,[7] Kavvadias, the favoured candidate of Prime Minister Charilaos Trikoupis,[12] succeeded Panagiotis Stamatakis as Ephor General of Antiquities, the head of the Greek Archaeological Service.

[29] In the early 1870s, the looting of the necropolis of Tanagra had seen some 10,000 tombs robbed and hundreds of antiquities, including vases and figurines, sold abroad, which outraged the Greek press and raised the issue of archaeological crime among the general population.

[115] He was also unable to prevent the export of significant antiquities, such as the Aineta aryballos (a seventh-century BCE Corinthian vase sold to the British Museum in 1866 by the epigrapher and art dealer Athanasios Rousopoulos [el]) and a series of funerary plaques, painted by Exekias, sold illegally to the German archaeologist Gustav Hirschfeld by the art dealer Anastasios Erneris in 1873.

[27] Under the new law, all antiquities ever discovered in Greece, whether on public or private land, were considered property of the state, closing the previous 'joint ownership' loophole.

Postolakas was acquitted by an Athenian court in April 1889, and the affair made Kavvadias several enemies: Reinach later wrote that the Ephor General had "lost his head a little".

28 August] 1909, a group of army officers known as the 'Military League'[120] carried out the Goudi coup,[121] which led to popular demonstrations against the political establishment[120] and the resignation of the prime minister, Dimitrios Rallis.

[7] Another source of opposition to Kavvadias within Greece was his support of the foreign schools of archaeology, which he was accused of privileging above the interests of native Greek archaeologists.

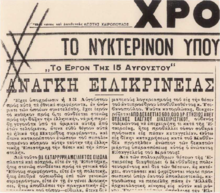

Three days later, the directors of the foreign schools published a joint riposte in the journal Estia, denying the accusations made in Chronos and praising Kavvadias for his "dominant role" in "render[ing] Athens its former prestige as metropolis for ancient studies".

[139] The school's thirty-six students in its first year included Semni Papaspyridi, Christos Karouzos and Spyridon Marinatos, all of whom went on to become leading figures in twentieth-century Greek archaeology.

Although the restorations made under Kavvadias's supervision by Nikolaos Balanos were later criticised and mostly reversed, the vision of the Acropolis and its monuments they created has been termed "the 'trade-mark' of modern Greece".

[1] In 2007, Petrakos named the foreign schools, and the excavations, publications and lectures that have taken part under their auspices, as a substantial factor behind making Athens "the major centre of Greek archaeology".

[158] Petrakos has accused him of "deliberate defamation" in his handling of the Archaeological Society of Athens,[159] and characterised his centralising approach to administration as "suffocating" the ephors who worked under him.