Pandora

The Pandora myth first appeared in lines 560–612 of Hesiod's poem in epic meter, the Theogony (c. 8th–7th centuries BCE), without ever giving the woman a name.

As before, she is created by Hephaestus, but now more gods contribute to her completion (63–82): Athena taught her needlework and weaving (63–4); Aphrodite "shed grace upon her head and cruel longing and cares that weary the limbs" (65–6); Hermes gave her "a shameless mind and a deceitful nature" (67–8); Hermes also gave her the power of speech, putting in her "lies and crafty words" (77–80); Athena then clothed her (72); next Persuasion and the Charites adorned her with necklaces and other finery (72–4); the Horae adorned her with a garland crown (75).

Finally, Hermes gives this woman a name: "Pandora [i.e. "All-Gift"], because all they who dwelt on Olympus gave each a gift, a plague to men who eat bread" (81–2).

Archaic and Classic Greek literature seem to make little further mention of Pandora, but mythographers later filled in minor details or added postscripts to Hesiod's account.

The mistranslation of pithos, a large storage jar, as "box"[14] is usually attributed to the sixteenth century humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam when he translated Hesiod's tale of Pandora into Latin.

[19] He writes that in earlier myths, Pandora was married to Prometheus, and cites the ancient Hesiodic Catalogue of Women as preserving this older tradition, and that the jar may have at one point contained only good things for humanity.

In view of such evidence, William E. Phipps has pointed out, "Classics scholars suggest that Hesiod reversed the meaning of the name of an earth goddess called Pandora (all-giving) or Anesidora (one-who-sends-up-gifts).

"[22] Jane Ellen Harrison[23] also turned to the repertory of vase-painters to shed light on aspects of myth that were left unaddressed or disguised in literature.

On a fifth-century amphora in the Ashmolean Museum (her fig.71) the half-figure of Pandora emerges from the ground, her arms upraised in the epiphany gesture, to greet Epimetheus.

Both were motherless, and reinforced via opposite means the civic ideologies of patriarchy and the "highly gendered social and political realities of fifth-century Athens"[27]—Athena by rising above her sex to defend it, and Pandora by embodying the need for it.

An independent tradition that does not square with any of the Classical literary sources is in the visual repertory of Attic red-figure vase-painters, which sometimes supplements, sometimes ignores, the written testimony; in these representations the upper part of Pandora is visible rising from the earth, "a chthonic goddess like Gaia herself.

[31] In the late Pre-Raphaelite painting by John D. Batten, hammer-wielding workmen appear through a doorway, while in the foreground Hephaestus broods on the as yet unanimated figure of "Pandora".

There were also earlier English paintings of the newly created Pandora as surrounded by the heavenly gods presenting gifts, a scene also depicted on ancient Greek pottery.

[36] An early drawing, only preserved now in the print made of it by Luigi Schiavonetti, follows the account of Hesiod and shows Pandora being adorned by the Graces and the Hours while the gods look on.

But in the actual painting which followed much later, a subordinated Pandora is surrounded by gift-bearing gods and Minerva stands near her, demonstrating the feminine arts proper to her passive role.

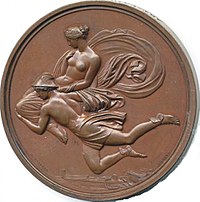

As well as the many European paintings of her from this period, there are examples in sculptures by Henri-Joseph Ruxthiel (1819),[39] John Gibson (1856),[40] Pierre Loison (1861, see above) and Chauncy Bradley Ives (1871).

It has been argued that it was as a result of the Hellenisation of Western Asia that the misogyny in Hesiod's account of Pandora began openly to influence both Jewish and then Christian interpretations of scripture.

Bishop Jean Olivier's long Latin poem Pandora drew on the Classical account as well as the Biblical to demonstrate that woman is the means of drawing men to sin.

[43] At the same period appeared a 5-act tragedy by the Protestant theologian Leonhard Culmann (1498-1568) titled Ein schön weltlich Spiel von der schönen Pandora (1544), similarly drawing on Hesiod in order to teach conventional Christian morality.

Accompanying an illustration of her opening the lid of an urn from which demons and angels emerge is a commentary that condemns "female curiosity and the desire to learn by which the very first woman was deceived".

[47] Again, Pietro Paolini's lively Pandora of about 1632 seems more aware of the effect that her pearls and fashionable headgear is making than of the evils escaping from the jar she holds.

[51] The same innocence informs Odilon Redon's 1910/12 clothed figure carrying a box and merging into a landscape suffused with light, and even more the 1914 version of a naked Pandora surrounded by flowers, a primaeval Eve in the Garden of Eden.

[53] In this work, Pandora, the statue in question, plays only a passive role in the competition between Prometheus and his brother Epimetheus (signifying the active life), and between the gods and men.

[54] There too the creator of a statue animates it with stolen fire, but then the plot is complicated when Jupiter also falls in love with this new creation but is prevented by Destiny from consummating it.

In revenge the god sends Destiny to tempt this new Eve into opening a box full of curses as a punishment for Earth's revolt against Heaven.

[55] If Pandora appears suspended between the roles of Eve and of Pygmalion's creation in Voltaire's work, in Charles-Pierre Colardeau's erotic poem Les Hommes de Prométhée (1774) she is presented equally as a love-object and in addition as an unfallen Eve: Not ever had the painter's jealous veil Shrouded the fair Pandora's charms: Innocence was naked and without alarm.

There Prometheus, having already stolen fire from heaven, creates a perfect female, "artless in nature, of limpid innocence", for which he anticipates divine vengeance.

[64] In England the high drama of the incident was travestied in James Robinson Planché's Olympic Revels or Prometheus and Pandora (1831), the first of the Victorian burlesques.

[65] At the other end of the century, Gabriel Fauré's ambitious opera Prométhée (1900) had a cast of hundreds, a huge orchestra and an outdoor amphitheatre for stage.

Best known in the end for a single metaphorical attribute, the box with which she was not even endowed until the 16th century, depictions of Pandora have been further confused with other holders of receptacles – with one of the trials of Psyche,[67] with Sophonisba about to drink poison[68] or Artemisia with the ashes of her husband.