Pankration

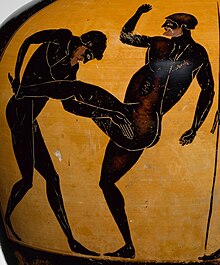

The athletes used boxing and wrestling techniques but also others, such as kicking, holds, joint locks, and chokes on the ground, making it similar to modern mixed martial arts.

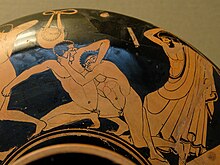

[2] In Greek mythology, it was said that the heroes Heracles and Theseus invented pankration as a result of using both wrestling and boxing in their confrontations with opponents.

[6] Pankration, as practiced in historical antiquity, was an athletic event that combined techniques of both boxing (pygmē/pygmachia – πυγμή/πυγμαχία) and wrestling (palē – πάλη), as well as additional elements, such as the use of strikes with the legs, to create a broad fighting sport similar to today's mixed martial arts competitions.

[citation needed] Pankratiasts were highly skilled grapplers and were extremely effective in applying a variety of takedowns, chokes and joint locks.

[8] Polyaemus describes King Philip II, the father of Alexander the Great, practicing with another pankratiast while his soldiers watched.

Arrhichion, Dioxippus, Polydamas of Skotoussa and Theogenes (often referred to as Theagenes of Thasos after the first century AD) are among the most highly recognized names.

[citation needed] Dioxippus was an Athenian who had won the Olympic Games in 336 BC, and was serving in Alexander the Great's army in its expedition into Asia.

[11] In 393 AD, the pankration, along with gladiatorial combat and all pagan festivals, was abolished by edict by the Christian Byzantine Emperor Theodosius I. Pausanias mentions the wrestler Leontiscus (Λεοντίσκος) from Messene.

In the Ancient Olympic Games specifically there were only two such age groups: men (andres – ἄνδρες) and boys (paides – παῖδες).

Grecophone satirist Lucian describes the process in detail: A sacred silver urn is brought, in which they have put bean-size lots.

[citation needed] There is evidence that the major Games in Greek antiquity easily had four tournament rounds, that is, a field of sixteen athletes.

Moreover, in the first century A.D., the Greco-Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria—who was himself probably a practitioner of pankration—makes a statement that could be an allusion to preliminary contests in which an athlete would participate and then collect his strength before coming forward fresh in the major competition.

The fallen opponent cannot relieve it, because his head is being shoved the opposite way by the left hand of the athlete executing the technique.

[19] In executing this choking technique (ἄγχειν – anchein), the athlete grabs the tracheal area (windpipe and "Adam's apple") between his thumb and his four fingers and squeezes.

Depending on the context, the term may refer to one of two variations of the technique, either arm can be used to apply the choke in both cases.

The word "naked" in this context suggests that, unlike other strangulation techniques found in jujutsu/judo, this hold does not require the use of a keikogi ("gi") or training uniform.

Another approach emphasizes less putting the opponent in an inverted vertical position and more the throw; it is shown in a sculpture in the metōpē (μετώπη) of the Hephaisteion in Athens, where Theseus is depicted heaving Kerkyōn.

This technique is described by the Roman poet Statius in his account of a match between the hero Tydeus of Thebes and an opponent in the Thebaid.

[6] As the pankration competitions were held outside and in the afternoon, appropriately positioning one's face in relation to the low sun was a major tactical objective.

The pankratiast, as well as the boxer, did not want to have to face the sun, as this would partly blind him to the blows of the opponent and make accurate delivery of strikes to specific targets difficult.

Theocritus, in his narration of the (boxing) match between Polydeukēs and Amykos, noted that the two opponents struggled a lot, vying to see who would get the sun's rays on his back.

The decision to remain standing or go to the ground obviously depended on the relative strengths of the athlete, and differed between anō and katō pankration.

It has been suggested that in antiquity, as today, falling to one's knee(s) was a metaphor for coming to a disadvantage and putting oneself at risk of losing the fight.

[21] High level athletes were also trained by special trainers who were called gymnastae (γυμνασταί),[21] some of whom had been successful pankration competitors themselves.

While specific styles taught by different teachers, in the mode of Asian martial arts, cannot be excluded, it is very clear (including in Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics) that the objective of a teacher of combat sports was to help each of his athletes to develop his personal style that would fit his strengths and weaknesses.

Among the multitude of the latter were also training tools that appear to be very similar to Asian martial arts forms or kata, and were known as cheironomia (χειρονομία) and anapale (ἀναπάλη).

Punching bags (kōrykos κώρυκος "leather sack") of different sizes and dummies were used for striking practice as well as for the hardening of the body and limbs.

Neo-Pankration (modern pankration) was first introduced to the martial arts community by Greek-American combat athlete Jim Arvanitis in 1969 and later exposed worldwide in 1973 when he was featured on the cover of Black Belt magazine.

Targeting any of the following areas of the body is also disallowed: neck, back of the head, throat, knees, elbows, joints, kidneys, groin and along the spine.

[29] Fighters wear protective gear (MMA gloves, shin pads, headgear) and fight in a standard wrestling mat.