Paraceratherium

Other genera of Oligocene indricotheres, such as Baluchitherium, Indricotherium, and Pristinotherium, have been named, but no complete specimens exist, making comparison and classification difficult.

Most modern scientists consider these genera to be junior synonyms of Paraceratherium, and it is thought to contain the following species; P. bugtiense, P. transouralicum, P. huangheense, and P. linxiaense.

The taxonomic history of Paraceratherium is complex due to the fragmentary nature of the known fossils and because Western, Soviet, and Chinese scientists worked in isolation from each other for much of the 20th century and published research mainly in their respective languages.

Many genera were named on the basis of subtle differences in molar tooth characteristics—features that vary within populations of other rhinoceros taxa—and are therefore not accepted by most scientists for distinguishing species.

Various indricothere remains were found in formations of the Mongolian Gobi Desert, including the legs of a specimen standing in an upright position, indicating that it had died while trapped in quicksand, as well as a very complete skull.

[16] In 2021, the Chinese palaeontologist Tao Deng and colleague described the new species P. linxiaense, based on a complete skull with an associated mandible and atlas bone from the Jiaozigou Formation of the Linxia Basin (to which the name refers) of northwestern China.

[5] In 1922 Forster-Cooper named the new species Metamynodon bugtiensis based on a palate and other fragments from Dera Bugti, thought to belong to a giant member of that genus.

[18][19] In 1936, the American palaeontologists Walter Granger and William K. Gregory proposed that Forster-Cooper's Baluchitherium osborni was likely a junior synonym (an invalid name for the same taxon) of Paraceratherium bugtiense, because these specimens were collected at the same locality and were possibly part of the same morphologically variable species.

By analysing alleged differences between named genera and species, Lucas and Sobus found that these most likely represented variation within populations, and that most features were indistinguishable between specimens, as had been pointed out in the 1930s.

[22] In 2013, the American palaeontologist Donald Prothero suggested that P. orgosensis may be distinct enough to warrant its original genus name Dzungariotherium, though its exact position requires evaluation.

[24] In contrast to the revision by Lucas and Sobus, a 2003 paper by Chinese palaeontologist Jie Ye and colleagues suggested that Indricotherium and Dzungariotherium were valid genera, and that P. prohorovi did not belong in Paraceratherium.

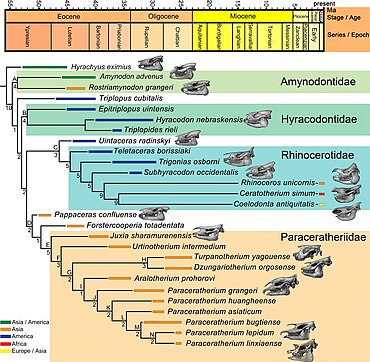

[28] In a 1999 cladistic study of tapiromorphs, the American palaeontologist Luke Holbrook found indricotheres to be outside the hyracodontid clade, and wrote that they may not be a monophyletic (natural) grouping.

The weight of Paraceratherium was similar to that of some extinct proboscideans, with the largest complete skeleton known belonging to the steppe mammoth (Mammuthus trogontherii).

The ears of elephants enlarge the body's surface area and are filled with blood vessels, making the dissipation of excess heat easier.

[41] In 1923, Matthew supervised an artist to draw a reconstruction of the skeleton based on the even less complete P. transouralicum specimens known by then, using the proportions of a modern rhinoceros as a guide.

P. transouralicum had robust maxillae and premaxillae, upturned zygomata, domed frontal bones, thick mastoid-paroccipital processes, a lambdoid crest that extended back, and occipital condyles with a vertical orientation.

[16] P. linxiaense differed from the other species in that the nasal notch was deeper, with the bottom placed above the middle of molar M2, a proportionally higher occipital condyle compared to the occipital surface's height, short muzzle bones and diastema in front of the cheek teeth, and a high zygomatic arch with a prominent hind end, and a smaller upper incisor I1.

[17] Unlike those of most primitive rhinocerotoids, the front teeth of Paraceratherium were reduced to a single pair of incisors in either jaw, which were large and conical, and have been described as tusks.

The atlas and axis vertebrae of the neck were wider than in most modern rhinoceroses, with space for strong ligaments and muscles that would be needed to hold up the large head.

The rest of the vertebrae were also very wide, and had large zygapophyses with much room for muscles, tendons, ligaments, and nerves, to support the head, neck, and spine.

[4] Like sauropod dinosaurs, Paraceratherium had pleurocoel-like openings (hollow parts of the bone) in their pre-sacral vertebrae, which probably helped to lighten the skeleton.

[4] Prothero suggests that animals as big as indricotheres would need very large home ranges or territories of at least 1,000 square kilometres (250,000 acres) and that, because of a scarcity of resources, there would have been little room in Asia for many populations or a multitude of nearly identical species and genera.

[30] Osborn suggested that its mode of foraging would have been similar to that of the high-browsing giraffe and okapi, rather than to modern rhinoceroses, whose heads are carried close to the ground.

[42] Remains assignable to Paraceratherium have been found in early to late Oligocene (34–23 million years ago) formations across Eurasia, in modern-day China, Mongolia, India, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Georgia, Turkey, Romania, Bulgaria, and the Balkans.

The range of Paraceratherium finds implies that they inhabited a continuous landmass with a similar environment across it, but this is contradicted by palaeogeographic maps that show this area had various marine barriers, so the genus was successful in being widely distributed despite this.

[50] A study of fossil pollen showed that much of China was woody shrubland, with plants such as saltbush, mormon tea (Ephedra), and nitre bush (Nitraria), all adapted to arid environments.

[51] The parts of China where Paraceratherium lived had dry lakes and abundant sand dunes, and the most common plant fossils are leaves of the desert-adapted Palibinia.

This implies the Tibetan region was not yet a high-elevation plateau that could act as a barrier, and large animals may therefore have been able to move freely along the eastern coast of the Tethys sea, and through lowlands in the area, some of which were possibly under 2,000 m (6,600 ft) in elevation at the time.

Prothero and the zoologist Pavel V. Putshkov have considered these causes unlikely since these animals managed to survive regardless of these issues for millions of years under the harsh conditions of their environment, and were not much larger than the biggest proboscideans, extinct as well as extant, which faced similar challenges.

[30][52] Putshkov and Andrzej H. Kulczicki instead suggested in 1995 and 2001 that invading gomphothere proboscideans from Africa in the late Oligocene (between 28 and 23 million years ago) may have considerably changed the habitats they entered, like African elephants do today.