Parallelogram

In Euclidean geometry, a parallelogram is a simple (non-self-intersecting) quadrilateral with two pairs of parallel sides.

The opposite or facing sides of a parallelogram are of equal length and the opposite angles of a parallelogram are of equal measure.

The congruence of opposite sides and opposite angles is a direct consequence of the Euclidean parallel postulate and neither condition can be proven without appealing to the Euclidean parallel postulate or one of its equivalent formulations.

By comparison, a quadrilateral with at least one pair of parallel sides is a trapezoid in American English or a trapezium in British English.

The three-dimensional counterpart of a parallelogram is a parallelepiped.

The word "parallelogram" comes from the Greek παραλληλό-γραμμον, parallēló-grammon, which means "a shape of parallel lines".

A simple (non-self-intersecting) quadrilateral is a parallelogram if and only if any one of the following statements is true:[2][3] Thus, all parallelograms have all the properties listed above, and conversely, if just any one of these statements is true in a simple quadrilateral, then it is considered a parallelogram.

All of the area formulas for general convex quadrilaterals apply to parallelograms.

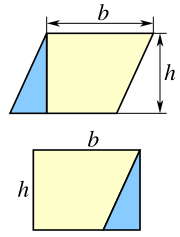

Further formulas are specific to parallelograms: A parallelogram with base b and height h can be divided into a trapezoid and a right triangle, and rearranged into a rectangle, as shown in the figure to the left.

This means that the area of a parallelogram is the same as that of a rectangle with the same base and height: The base × height area formula can also be derived using the figure to the right.

at the intersection of the diagonals:[9] When the parallelogram is specified from the lengths B and C of two adjacent sides together with the length D1 of either diagonal, then the area can be found from Heron's formula.

and the leading factor 2 comes from the fact that the chosen diagonal divides the parallelogram into two congruent triangles.

Then the area of the parallelogram generated by a and b is equal to

Then the signed area of the parallelogram with vertices at a, b and c is equivalent to the determinant of a matrix built using a, b and c as rows with the last column padded using ones as follows: To prove that the diagonals of a parallelogram bisect each other, we will use congruent triangles: (since these are angles that a transversal makes with parallel lines AB and DC).

Therefore, triangles ABE and CDE are congruent (ASA postulate, two corresponding angles and the included side).

Parallelograms can tile the plane by translation.

If edges are equal, or angles are right, the symmetry of the lattice is higher.

An automedian triangle is one whose medians are in the same proportions as its sides (though in a different order).

Varignon's theorem holds that the midpoints of the sides of an arbitrary quadrilateral are the vertices of a parallelogram, called its Varignon parallelogram.

If the quadrilateral is convex or concave (that is, not self-intersecting), then the area of the Varignon parallelogram is half the area of the quadrilateral.

Each pair of conjugate diameters of an ellipse has a corresponding tangent parallelogram, sometimes called a bounding parallelogram, formed by the tangent lines to the ellipse at the four endpoints of the conjugate diameters.

All tangent parallelograms for a given ellipse have the same area.

It is possible to reconstruct an ellipse from any pair of conjugate diameters, or from any tangent parallelogram.

A parallelepiped is a three-dimensional figure whose six faces are parallelograms.