Parareptilia

Parareptilia ("near-reptiles") is an extinct clade of basal sauropsids/reptiles, typically considered the sister taxon to Eureptilia (the group that likely contains all living reptiles and birds).

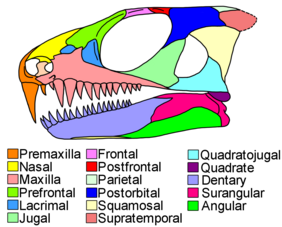

[2][3] Compared to most eureptiles, parareptiles retained fairly "primitive" characteristics such as robust, low-slung bodies and large supratemporal bones at the back of the skull.

While all but the earliest eureptiles were diapsids, with two openings at the back of the skull, parareptiles were generally more conservative in the extent of temporal fenestration.

In its modern usage, Parareptilia was first utilized as a cladistically correct alternative to Anapsida, a term which historically referred to reptiles with solid skulls lacking holes behind the eyes.

They also had several unique adaptations, such as a large pit on the maxilla, a broad prefrontal-palatine contact, and the absence of a supraglenoid foramen of the scapula.

[4][9][7] The rest of the skull was often strongly-textured by pits, ridges, and rugosities in most parareptile groups, occasionally culminating in complex bosses or spines.

In all parareptiles except mesosaurs, the prefrontal has a plate-like inner branch which forms a broad contact with the palatine bone of the palate.

However, a growing number of parareptile taxa are known to have had an infratemporal fenestra, a large hole or emargination lying among the bones behind the eye.

Both the tooth-bearing dentary bone and the posterior foramen intermandibularis (a hole on the inner surface of the jaw) reach as far back as the coronoid process.

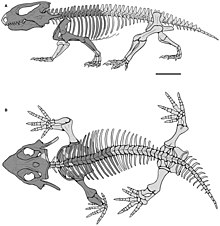

[13] There was some variation in the body shape of parareptiles, with early members of the group having an overall lizard-like appearance, with thin limbs and long tails.

The most successful and diverse groups of parareptiles, the pareiasaurs and procolophonids, had massively-built bodies with reduced tails and stout limbs with short digits.

Unlike early eureptiles, the outer part of the lower humerus possessed both a small supinator process and an ectepicondylar foramen and groove.

Gauthier et al. (1988) provided the first phylogenetic definitions for the names of many amniote taxa and argued that captorhinids and turtles were sister groups, constituting the clade Anapsida (in a much more limited context than typically applied).

Olsen's term "parareptiles" was chosen to refer to this clade, although its instability within their analysis meant that Gauthier et al. (1988) were not confident enough to erect Parareptilia as a formal taxon.

Their cladogram is as follows:[16] Synapsida †Mesosauridae †Procolophonidae †Millerettidae †Pareiasauria †Captorhinidae Testudines †Protorothyrididae Diapsida Laurin & Reisz (1995) found a slightly different topology, in which Reptilia is divided into Parareptilia and Eureptilia.

The cladogram of Laurin & Reisz (1995) is provided below:[4] Synapsida †Mesosauridae †Millerettidae †Pareiasauria †Procolophonidae Testudines †Captorhinidae †Protorothyrididae Diapsida In contrast, several studies in the mid-to-late 1990s by Olivier Rieppel and Michael deBraga argued that turtles were actually lepidosauromorph diapsids related to the sauropterygians.

With turtles positioned outside of parareptiles, Tsuji and Müller (2009) redefined Parareptilia as "the most inclusive clade containing Milleretta rubidgei and Procolophon trigoniceps, but not Captorhinus aguti.