Parasitism

Although parasitism is often unambiguous, it is part of a spectrum of interactions between species, grading via parasitoidism into predation, through evolution into mutualism, and in some fungi, shading into being saprophytic.

In early modern times, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek observed Giardia lamblia with his microscope in 1681, while Francesco Redi described internal and external parasites including sheep liver fluke and ticks.

For example, the trematode Zoogonus lasius, whose sporocysts lack mouths, castrates the intertidal marine snail Tritia obsoleta chemically, developing in its gonad and killing its reproductive cells.

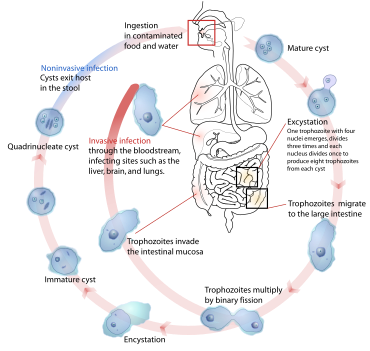

[27] Autoinfection, where (by exception) the whole of the parasite's life cycle takes place in a single primary host, can sometimes occur in helminths such as Strongyloides stercoralis.

They include annelids such as leeches, crustaceans such as branchiurans and gnathiid isopods, various dipterans such as mosquitoes and tsetse flies, other arthropods such as fleas and ticks, vertebrates such as lampreys, and mammals such as vampire bats.

Examples include the large blue butterfly, Phengaris arion, its larvae employing ant mimicry to parasitise certain ants,[38] Bombus bohemicus, a bumblebee which invades the hives of other bees and takes over reproduction while their young are raised by host workers, and Melipona scutellaris, a eusocial bee whose virgin queens escape killer workers and invade another colony without a queen.

[41] Adelphoparasitism, (from Greek ἀδελφός (adelphós), brother[58]), also known as sibling-parasitism, occurs where the host species is closely related to the parasite, often in the same family or genus.

Species of Striga (witchweeds) are estimated to cost billions of dollars a year in crop yield loss, infesting over 50 million hectares of cultivated land within Sub-Saharan Africa alone.

Necrotrophic pathogens on the other hand, kill host cells and feed saprophytically, an example being the root-colonising honey fungi in the genus Armillaria.

To give a few examples, Bacillus anthracis, the cause of anthrax, is spread by contact with infected domestic animals; its spores, which can survive for years outside the body, can enter a host through an abrasion or may be inhaled.

[80] Viruses are obligate intracellular parasites, characterised by extremely limited biological function, to the point where, while they are evidently able to infect all other organisms from bacteria and archaea to animals, plants and fungi, it is unclear whether they can themselves be described as living.

[93] Long-term partnerships can lead to a relatively stable relationship tending to commensalism or mutualism, as, all else being equal, it is in the evolutionary interest of the parasite that its host thrives.

[92][97] Among competing parasitic insect-killing bacteria of the genera Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus, virulence depended on the relative potency of the antimicrobial toxins (bacteriocins) produced by the two strains involved.

For example, in the California coastal salt marsh, the fluke Euhaplorchis californiensis reduces the ability of its killifish host to avoid predators.

[106] An extreme example is the myxosporean Henneguya zschokkei, an ectoparasite of fish and the only animal known to have lost the ability to respire aerobically: its cells lack mitochondria.

[111] The evolutionary biologist W. D. Hamilton suggested that sexual reproduction could have evolved to help to defeat multiple parasites by enabling genetic recombination, the shuffling of genes to create varied combinations.

[112][113] However, there may be a trade-off between immunocompetence and breeding male vertebrate hosts' secondary sex characteristics, such as the plumage of peacocks and the manes of lions.

[110] Plants respond to parasite attack with a series of chemical defences, such as polyphenol oxidase, under the control of the jasmonic acid-insensitive (JA) and salicylic acid (SA) signalling pathways.

There were philosophical differences, too: Poulin notes that, influenced by medicine, "many parasitologists accepted that evolution led to a decrease in parasite virulence, whereas modern evolutionary theory would have predicted a greater range of outcomes".

Even though the parasite was eradicated in all but four countries, the worm began using frogs as an intermediary host before infecting dogs, making control more difficult than it would have been if the relationships had been better understood.

Log-transformation of data before the application of parametric test, or the use of non-parametric statistics is recommended by several authors, but this can give rise to further problems, so quantitative parasitology is based on more advanced biostatistical methods.

In ancient Greece, parasites including the bladder worm are described in the Hippocratic Corpus, while the comic playwright Aristophanes called tapeworms "hailstones".

[128] In his Canon of Medicine, completed in 1025, the Persian physician Avicenna recorded human and animal parasites including roundworms, threadworms, the Guinea worm and tapeworms.

[129][130] In the early modern period, Francesco Redi's 1668 book Esperienze Intorno alla Generazione degl'Insetti (Experiences of the Generation of Insects), explicitly described ecto- and endoparasites, illustrating ticks, the larvae of nasal flies of deer, and sheep liver fluke.

[131] Redi was the first to name the cysts of Echinococcus granulosus seen in dogs and sheep as parasitic; a century later, in 1760, Peter Simon Pallas correctly suggested that these were the larvae of tapeworms.

[128] A few years later, in 1687, the Italian biologists Giovanni Cosimo Bonomo and Diacinto Cestoni described scabies as caused by the parasitic mite Sarcoptes scabiei, marking it as the first disease of humans with a known microscopic causative agent.

[128] Algernon Thomas and Rudolf Leuckart independently made the first discovery of the life cycle of a trematode, the sheep liver fluke, by experiment in 1881–1883.

[139][140] Poulin observes that the widespread prophylactic use of anthelmintic drugs in domestic sheep and cattle constitutes a worldwide uncontrolled experiment in the life-history evolution of their parasites.

[141] In the classical era, the concept of the parasite was not strictly pejorative: the parasitus was an accepted role in Roman society, in which a person could live off the hospitality of others, in return for "flattery, simple services, and a willingness to endure humiliation".

[153] Its human hosts initially become violent "infected" beings, before turning into blind zombie "clickers", complete with fruiting bodies growing out from their faces.