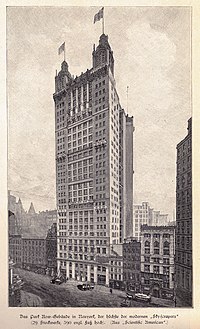

Park Row Building

The architectural detail on the facade includes large columns and pilasters, as well as numerous ornamental overhanging balconies.

Upon completion, about 4,000 people worked at the Park Row Building, with tenants such as the Associated Press and the Interborough Rapid Transit Company.

However, the center of the southwestern elevation (facing the eastern corner of Park Row and Ann Street) contains a light court so the upper floors resemble a backward, warped "E", with the "spine" running along the northeastern facade.

[31][32] The first and second stories are largely a commercial storefront with bronze-and-glass infill, though two granite Doric-style pilasters from the original design remain extant, at the extreme outer ends of this elevation.

[4][31] The first- and second-story facade to either side of the main entrance is slightly asymmetrical, with two pilasters to the north and three to the south.

The windows on the 23rd floor contain thick pedestals that support terracotta Doric columns spanning the 24th through 26th stories.

[b] The southern and eastern elevations, as well as the light court facing southwest, have single, double, or triple windows set within a bare brick facade.

[23][39][40][c] Underneath the subbasement level are 3,900 Georgia spruce piles, each 20 feet (6.1 m) deep with a 12-inch (300 mm) diameter, driven into wet sand.

[23][47] When built, the Park Row Building also contained two steel water tanks of 10,000 US gallons (38,000 L), one in the cellar and one on the roof.

[50] These elevators were manufactured by Sprague Electric, and were one of the company's last major installations in New York City; this model quickly became unpopular after the Park Row Building's opening.

[39] The outer lobby design dates from 1930 and has a terrazzo floor; a pink-marble wall with black-marble bases; a plaster cornice; and an octagonal ceiling lamp.

The ceiling is made of plaster with ornate decoration and deep coffers, contains a Greek cornice, and is supported by a row of square piers through the center of the lobby.

[19][36] The main lobby extends to a stair to the southeast, which has black marble risers, terrazzo treads, and a bronze handrail.

[52] On the building's northern side, there are two staircases above the second floor, with cast-iron risers, marble treads, and wrought-iron railings with wooden handrails.

Another hallway connected to the northern end of the easterly passageway, leading southeast and then south to the offices overlooking Theatre Alley.

A spiral stair made of cast-iron connects the 28th through 30th floors, surrounding a curved elevator shaft with cast- and wrought-iron doors.

[6] In 1896, seven lots at 15 Park Row were purchased by William Mills Ivins Sr.,[5][56] a prominent lawyer and former judge advocate general for New York State.

[57] He was acting on behalf of an investment syndicate that included wealthy businessman August Belmont Jr., for which he was employed as legal counsel.

[58] The syndicate was unable to buy the corner lots on Ann Street "at any reasonable price", resulting in the unusual shape of the building.

[16][26] The Park Row Building also had several tenants who engaged in suspicious activity, such as a bucket shop in 1901,[70] a get-rich-quick scheme in 1903,[71] and a gambling ring in 1904.

In October 1924, McNeil sold the buildings to Bernard Dorf in exchange for the Theodore Roosevelt Apartments on the Bronx's Grand Concourse, in a sale worth $12 million.

[82] The building received few modifications throughout the remainder of the century, except for the replacement of windows and refurbishment of the lobby's original ceiling.

[92] Atlas Capital Group bought the Park Row Building from the Friedman family in January 2021 for about $140 million.

[94] By early 2022, residents had raised complaints that the building's elevators, heat, water, and gas services sometimes did not work properly.

[95] That March, chef Todd English agreed to lease 22,000 square feet (2,000 m2) in the building's lower stories and open a restaurant there.

He was being held with Roberto Elia by the Justice Department in connection with a series of bombings that had occurred in New York City, Boston, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Paterson, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh.

[16] A critic, writing in the Real Estate Record and Guide in 1898, stated that "New York is the only city in which such a monster would be allowed to rear itself", and called the blank side walls "absolutely inexpressive and vacuous", except for the steel girders across the light court that were "provided to give the inmates of the central part some allowance of light and air".

[102] The unnamed critic described the cupolas as "insignificant terminations which add nothing", in contrast to the top stories of the St. Paul Building, which they felt was well designed.

[47] Architectural critic Montgomery Schuyler stated in 1897 that he believed skyscrapers should be divided into three horizontal layers but that "Mr. Robertson declines to recognize even this convention" in general.

[16][105] Scientific American, in 1898, praised Robertson's design as having a "very satisfactory effect", in that the facade was able to "clothe the 'skeleton; with a mantle of stone and glass that shall appear diversified, dignified and appropriate".