Pascaline

In 1649, King Louis XIV gave Pascal a royal privilege (similar to a patent), which provided the exclusive right to design and manufacture calculating machines in France.

[6] In 1820, Thomas de Colmar designed his arithmometer, the first mechanical calculator strong enough and reliable enough to be used daily in an office environment.

Pascal received a Royal Privilege in 1649 that granted him exclusive rights to make and sell calculating machines in France.

By that time Pascal had moved on to the study of religion and philosophy, which resulted in both the Lettres provinciales and the Pensées.

Speeches given during the event highlighted Pascal's practical achievements when he was already known in the field of pure mathematics, and his creative imagination, along with how ahead of their time both the machine and its inventor were.

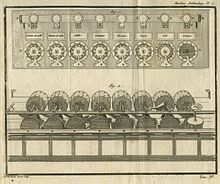

To add a 5, one must insert a stylus between the spokes that surround the number 5 and rotate the wheel clockwise all the way to the stop lever.

The carry would turn every input wheel one by one in a very rapid Domino effect fashion and all the display registers would be reset.

[18] Additions are performed with the display bar moved closest to the edge of the machine, showing the direct value of the accumulator.

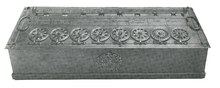

The following table shows all the steps required to compute 54,321 − 12,345 = 41,976 Pascalines came in both decimal and non-decimal varieties, both of which can be viewed in museums today.

The metric system was adopted in France on December 10, 1799, by which time Pascal's basic design had inspired other craftsmen, although with a similar lack of commercial success.

Pascal planned to distribute the Pascaline broadly in order to reduce the workload for people who needed to perform laborious arithmetic.

[24] Drawing inspiration from his father, a tax commissioner, Pascal hoped to provide a shortcut to hours of number crunching performed by workers in professions such as mathematics, physics, astronomy, etc.

[25] But, because of the intricacies of the device, the relationship Pascal had with craftsmen, and the intellectual property laws he influenced, the production of the Pascaline was far more limited than he had envisioned.

[24] In 1645, in order to control the production of his invention, Pascal wrote to Monseigneur Le Chancelier (the chancellor of France, Pierre Séguier) in his letter entitled "La Machine d’arithmétique.

[24] His ingenuity garnered the respect of King Louis XIV of France who granted his request, but it came at a price; craftsmen were not able to legally experiment with Pascal's design, nor were they able to distribute his machine without his permission/guidance.

This affected Pascal’s ability to recruit talent as guilds often reduced the exchange of ideas and trade; sometimes, craftsmen would withhold their labour altogether to rebel against the nobles.

As Pascal described artisans: “[they] work through groping trial and error, that is, without certain measures and proportions regulated by art, produc[ing] nothing corresponding to what they had sought, or, what’s more, they make a little monster appear, that lacks its principal limbs, the others being deformed, lacking any proportion.”[30] Pascal operated his project with this hierarchy in mind: he invented and thought, while the artisans simply executed.

"[30] In contrast, Samuel Morland, one of Pascal's contemporaries also working on creating a calculating machine, likely succeeded because of his ability to manage good relations with his craftsmen.

Morland proudly attributed part of his invention to the artisans by name– an odd thing for a nobleman to do for a commoner at the time.

His first craftsmen was the famous Peter Blondeau, who had already received protection and recognition from French statesman Richelieu for his contributions in producing coinage for England.

Morland's other craftsmen were similarly accomplished: the third, Dutchman John Fromanteel, came a famous Dutch family who pioneered the pendulum clock.

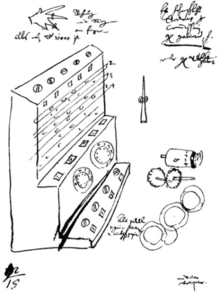

[31] Besides being the first calculating machine made public during its time, the pascaline is also: In 1957, Franz Hammer, a biographer of Johannes Kepler, announced the discovery of two letters that Wilhelm Schickard had written to his friend Johannes Kepler in 1623 and 1624 which contain the drawings of a previously unknown working calculating clock, predating Pascal's work by twenty years.

[37] After careful examination it was found, in contradiction to Franz Hammer's understanding, that Schickard's drawings had been published at least once per century starting from 1718.

[38] Bruno von Freytag Loringhoff, a mathematics professor at the University of Tübingen built the first replica of Schickard's machine but not without adding wheels and springs to finish the design.

[40] Schickard's machine used clock wheels which were made stronger and were therefore heavier, to prevent them from being damaged by the force of an operator input.

The cumulative friction and inertia of all these wheels could "...potentially damage the machine if a carry needed to be propagated through the digits, for example like adding 1 to a number like 9,999".

[41] The great innovation in Pascal's calculator was that it was designed so that each input wheel is totally independent from all the others and carries are propagated in sequence.

He then devised a competing design, the Stepped Reckoner which was meant to perform additions, subtractions and multiplications automatically and division under operator control.

[42] Only the machine built in 1694 is known to exist; it was rediscovered at the end of the 19th century, having spent 250 years forgotten in an attic at the University of Göttingen.

[42] The German calculating-machine inventor Arthur Burkhardt was asked to attempt to put Leibniz' machine in operating condition.