Mechanical calculator

Surviving notes from Wilhelm Schickard in 1623 reveal that he designed and had built the earliest of the modern attempts at mechanizing calculation.

His machine was composed of two sets of technologies: first an abacus made of Napier's bones, to simplify multiplications and divisions first described six years earlier in 1617, and for the mechanical part, it had a dialed pedometer to perform additions and subtractions.

A study of the surviving notes shows a machine that would have jammed after a few entries on the same dial,[1] and that it could be damaged if a carry had to be propagated over a few digits (like adding 1 to 999).

Two decades after Schickard's supposedly failed attempt, in 1642, Blaise Pascal decisively solved these particular problems with his invention of the mechanical calculator.

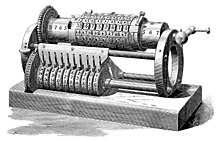

It used a stepped drum, built by and named after him, the Leibniz wheel, was the first two-motion calculator, the first to use cursors (creating a memory of the first operand) and the first to have a movable carriage.

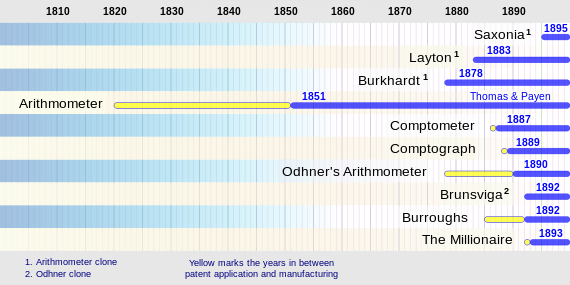

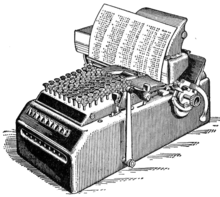

[7] Thomas' arithmometer, the first commercially successful machine, was manufactured two hundred years later in 1851; it was the first mechanical calculator strong enough and reliable enough to be used daily in an office environment.

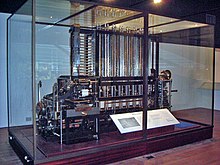

Charles Babbage designed two new kinds of mechanical calculators, which were so big that they required the power of a steam engine to operate, and that were too sophisticated to be built in his lifetime.

[11] The second one was a programmable mechanical calculator, his analytical engine, which Babbage started to design in 1834; "in less than two years he had sketched out many of the salient features of the modern computer.

This desire has led to the design and construction of a variety of aids to calculation, beginning with groups of small objects, such as pebbles, first used loosely, later as counters on ruled boards, and later still as beads mounted on wires fixed in a frame, as in the abacus.

[17] In a sense, Pascal's invention was premature, in that the mechanical arts in his time were not sufficiently advanced to enable his machine to be made at an economic price, with the accuracy and strength needed for reasonably long use.

In 1623 and 1624 Wilhelm Schickard, in two letters that he sent to Johannes Kepler, reported his design and construction of what he referred to as an “arithmeticum organum” (“arithmetical instrument”), which would later be described as a Rechenuhr (calculating clock).

Schickard's machine used clock wheels which were made stronger and were therefore heavier, to prevent them from being damaged by the force of an operator input.

Accordingly, he eventually designed an entirely new machine called the Stepped Reckoner; it used his Leibniz wheels, was the first two-motion calculator, the first to use cursors (creating a memory of the first operand) and the first to have a movable carriage.

Leibniz went even further in relation to the ability to use a moveable carriage to perform multiplication more efficiently, albeit at the expense of a fully working carry mechanism.

Nevertheless, while always improving on it, I found reasons to change its design...When, several years ago, I saw for the first time an instrument which, when carried, automatically records the numbers of steps by a pedestrian, it occurred to me at once that the entire arithmetic could be subjected to a similar kind of machinery so that not only counting but also addition and subtraction, multiplication and division could be accomplished by a suitably arranged machine easily, promptly, and with sure results.The principle of the clock (input wheels and display wheels added to a clock like mechanism) for a direct-entry calculating machine couldn't be implemented to create a fully effective calculating machine without additional innovation with the technological capabilities of the 17th century.

[57] The mechanical calculator industry started in 1851 Thomas de Colmar released his simplified Arithmomètre, which was the first machine that could be used daily in an office environment.

[61] The cash register, invented by the American saloonkeeper James Ritty in 1879, addressed the old problems of disorganization and dishonesty in business transactions.

[74] It was a pure adding machine coupled with a printer, a bell and a two-sided display that showed the paying party and the store owner, if he wanted to, the amount of money exchanged for the current transaction.

The cash register was easy to use and, unlike genuine mechanical calculators, was needed and quickly adopted by a great number of businesses.

[75] In 1890, 6 years after John Patterson started NCR Corporation, 20,000 machines had been sold by his company alone against a total of roughly 3,500 for all genuine calculators combined.

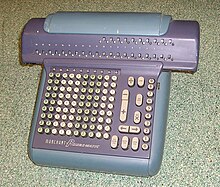

Numerous designs, notably European calculators, had handcranks, and locks to ensure that the cranks were returned to exact positions once a turn was complete.

The Dalton adding-listing machine introduced in 1902 was the first of its type to use only ten keys, and became the first of many different models of "10-key add-listers" manufactured by many companies.

Friden made a calculator that also provided square roots, basically by doing division, but with added mechanism that automatically incremented the number in the keyboard in a systematic fashion.

This kind of machine included the Original Odhner, Brunsviga and several following imitators, starting from Triumphator, Thales, Walther, Facit up to Toshiba.

Hamann calculators externally resembled pinwheel machines, but the setting lever positioned a cam that disengaged a drive pawl when the dial had moved far enough.

Among the major manufacturers were Mercedes-Euklid, Archimedes, and MADAS in Europe; in the USA, Friden, Marchant, and Monroe were the principal makers of rotary calculators with carriages.

They engaged drive gears in the body of the machine, which rotated them at speeds proportional to the digit being fed to them, with added movement (reduced 10:1) from carries created by dials to their right.

There is no way to develop the needed movement from a driveshaft that rotates one revolution per cycle with few gears having practical (relatively small) numbers of teeth.

For sterling currency, £/s/d (and even farthings), there were variations of the basic mechanisms, in particular with different numbers of gear teeth and accumulator dial positions.

[87] Stylus-operated adders with circular slots for the stylus, and side-by -side wheels, as made by Sterling Plastics (USA), had an ingenious anti-overshoot mechanism to ensure accurate carries.