Pastoralism

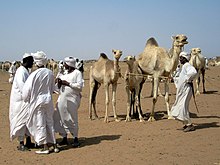

[2] The animal species involved include cattle, camels, goats, yaks, llamas, reindeer, horses, and sheep.

[3] Pastoralism occurs in many variations throughout the world, generally where environmentally effected characteristics such as aridity, poor soils, cold or hot temperatures, and lack of water make crop-growing difficult or impossible.

Operating in more extreme environments with more marginal lands means that pastoral communities are very vulnerable to the effects of global warming.

[4] Pastoralism remains a way of life in many geographic areas, including Africa, the Tibetan plateau, the Eurasian steppes, the Andes, Patagonia, the Pampas, Australia and many other places.

The enclosure of common lands has led to Sedentary pastoralism becoming more common as the hardening of political borders, land tenures, expansion of crop farming, and construction of fences and dedicated agricultural buildings all reduce the ability to move livestock around freely, leading to the rise of pastoral farming on established grazing-zones (sometimes called "ranches").

In many places, grazing herds on savannas and in woodlands can help maintain the biodiversity of such landscapes and prevent them from evolving into dense shrublands or forests.

Foraging strategies have included hunting or trapping big game and smaller animals, fishing, collecting shellfish or insects, and gathering wild-plant foods such as fruits, seeds, and nuts.

McCabe noted that when common property institutions are created, in long-lived communities, resource sustainability is much higher, which is evident in the East African grasslands of pastoralist populations.

Mobility allows pastoralists to adapt to the environment, which opens up the possibility for both fertile and infertile regions to support human existence.

Important components of pastoralism include low population density, mobility, vitality, and intricate information systems.

[15] The Maquis shrublands of the Mediterranean region are dominated by pyrophytic plants that thrive under conditions of anthropogenic fire and livestock grazing.

[16] Nomadic pastoralists have a global food-producing strategy depending on the management of herd animals for meat, skin, wool, milk, blood, manure, and transport.

Pastoralist societies have had field armed men protect their livestock and their people and then to return into a disorganized pattern of foraging.

With the growth of nation states in Asia since the mid-twentieth century, mobility across the international borders in these countries have tended to be more and more restricted and regulated.

[citation needed] Different mobility patterns can be observed: Somali pastoralists keep their animals in one of the harshest environments but they have evolved over the centuries.

ReliefWeb reported that "Several hundred million people practice pastoralism—the use of extensive grazing on rangelands for livestock production, in over 100 countries worldwide.

"[31] Pastoralists manage rangelands covering about a third of the Earth's terrestrial surface and are able to produce food where crop production is not possible.

Pastoralism has been shown, "based on a review of many studies, to be between 2 and 10 times more productive per unit of land than the capital intensive alternatives that have been put forward".

However, many of these benefits go unmeasured and are frequently squandered by policies and investments that seek to replace pastoralism with more capital intensive modes of production.

[citation needed] There is a variation in genetic makeup of the farm animals driven mainly by natural and human based selection.

[34] For example, pastoralists in large parts of Sub Saharan Africa are preferring livestock breeds which are adapted to their environment and able to tolerate drought and diseases.

She argued that a common-pool resource, such as grazing lands used for pastoralism, can be managed more sustainably through community groups and cooperatives than through privatization or total governmental control.

[citation needed] The violent herder–farmer conflicts in Nigeria, Mali, Sudan, Ethiopia and other countries in the Sahel and Horn of Africa regions have been exacerbated by climate change, land degradation, and population growth.