Saka

[23] Linguist Oswald Szemerényi studied synonyms of various origins for Scythian and differentiated the following terms: Sakā 𐎿𐎣𐎠, Skuthēs Σκύθης, Skudra 𐎿𐎤𐎢𐎭𐎼, and Sugᵘda 𐎿𐎢𐎦𐎢𐎭.

[24] Derived from an Iranian verbal root sak-, "go, roam" (related to "seek") and thus meaning "nomad" was the term Sakā, from which came the names: From the Indo-European root (s)kewd-, meaning "propel, shoot" (and from which was also derived the English word shoot), of which *skud- is the zero-grade form, was descended the Scythians' self-name reconstructed by Szemerényi as *Skuδa (roughly "archer").

[51] The Achaemenid king Xerxes I listed the Saka coupled with the Dahā (𐎭𐏃𐎠) people of Central Asia,[45][47][44] who might possibly have been identical with the Sakā tigraxaudā.

[37] Some other Saka groups lived to the east of the Pamir Mountains and to the north of the Iaxartes river,[59] as well as in the regions corresponding to modern-day Qirghizia, Tian Shan, Altai, Tuva, Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Kazakhstan.

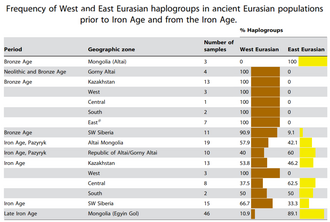

[66] Genetic evidence corroborates archaeological findings, suggesting an initial eastwards expansion of Western Steppe Herders towards the Altai region and Western Mongolia, spreading Iranian languages, and subsequent contact episodes with local Siberian and Eastern Asian populations, giving rise to the initial (Eastern) Scythian material cultures (Saka).

[78] Darius I waged wars against the eastern Sakas during a campaign of 520 to 518 BC where, according to his inscription at Behistun, he conquered the Massagetae/Sakā tigraxaudā, captured their king Skunxa, and replaced him with a ruler who was loyal to Achaemenid rule.

[127][128] The Yuehzhi, themselves under attacks from another nomadic tribe, the Wusun, in 133–132 BC, moved, again, from the Ili and Chu valleys, and occupied the country of Daxia, (大夏, "Bactria").

[62][129] The ancient Greco-Roman geographer Strabo noted that the four tribes that took down the Bactrians in the Greek and Roman account – the Asioi, Pasianoi, Tokharoi and Sakaraulai – came from land north of the Syr Darya where the Ili and Chu valleys are located.

[134] Migrations of the 2nd and 1st century BC have left traces in Sogdia and Bactria, but they cannot firmly be attributed to the Saka, similarly with the sites of Sirkap and Taxila in ancient India.

The scholar Bryan Levman however criticised this hypothesis for resting on slim to no evidence, and maintains that the Shakyas were a population native to the north-east Gangetic plain who were unrelated to Iranic Sakas.

[142][144] According to historian Michael Mitchiner, the Abhira tribe were a Saka people cited in the Gunda inscription of the Western Satrap Rudrasimha I dated to AD 181.

Herodotus (IV.64) describes them as Scythians, although they figure under a different name: The Sacae, or Scyths, were clad in trousers, and had on their heads tall stiff caps rising to a point.

Such is the life of the other nomads also, who are always attacking their neighbors and then in turn settling their differences.The Sakas receive numerous mentions in Indian texts, including the Purāṇas, the Manusmṛiti, the Rāmāyaṇa, the Mahābhārata, and the Mahābhāṣya of Patanjali.

For example, in a 2002 study the mitochondrial DNA of Saka period male and female skeletal remains from a double inhumation kurgan at the Beral site in Kazakhstan was analysed.

They studied the haplotypes and haplogroups of 26 ancient human specimens from the Krasnoyarsk area in Siberia dated from between the middle of the 2nd millennium BC and the 4th century AD (Scythian and Sarmatian timeframe).

[166] According to Tikhonov, et al. (2019), the Eastern Scythians and the Xiongnu "possibly bore proto-Turkic elements", based on a continuation of maternal and paternal haplogroups.

[172] Two other genetic studies published in 2021 and 2022 found that the Saka originated from a shared WSH-like (Srubnaya, Sintashta, and Andronovo culture) background with additional BMAC and East Eurasian-like ancestry.

[181] Genetic data across Eurasia suggest that the Scythian cultural phenomenon was accompanied by some degree of migration from east to west, starting in the area of the Altai region.

[182] In particular, the Classical Scythians of the western Eurasian steppe were not direct descendants of the local Bronze Age populations, but partly resulted from this east-west spread.

[183] As a result, a large-scale integrated union of nomads from Central Asia formed in the area in the 5th–4th century BCE, with fairly uniformized cultural practices.

[183] This cultural complex, with notable ‘‘foreign elements’’, corresponds to the ‘‘royal’’ burials of Filippovka kurgan, and define the "Prokhorovka period" of the Early Sarmatians.

These artifacts included golf harness fittings, pendants, chains, appliqués, and more – most of which are in the Animal Style of the Scythian-Saka era dating back to the 5th–4th centuries BC.

[205] During the 18th century and the Russian expansion into Siberia, many Saka kurgans were plundered, sometimes by independent grave-robbers or sometimes officially at the instigation of Peter the Great, but usually without any archaeological records being taken.

[206] A site found in 1968 in Tillia Tepe (literally "the golden hill") in northern Afghanistan (former Bactria) near Shebergan consisted of the graves of five women and one man with extremely rich jewelry, dated to around the 1st century BC, and probably related to that of Saka tribes normally living slightly to the north.

These items provide valuable insights into the material culture and lifestyle of the Scythians, including their hunting and warfare practices, and their use of animal hides for clothing.

Excavations of the prehistoric art of the Dian civilisation of Yunnan have revealed hunting scenes of Caucasoid horsemen in Central Asian clothing.

[217] Similar to other eastern Iranian peoples represented on the reliefs of the Apadana at Persepolis, Sakas are depicted as wearing long trousers, which cover the uppers of their boots.

Asian Saka headgear is clearly visible on the Persepolis Apadana staircase bas-relief – high pointed hat with flaps over ears and the nape of the neck.

[224] From China to the Danube delta, men seemed to have worn a variety of soft headgear – either conical like the one described by Herodotus, or rounder, more like a Phrygian cap.

Two monsters resembling griffins decorate the chest, and on the left arm are three partially obliterated images which seem to represent two deer and a mountain goat.

Obv: Kharosthi legend, "Of the great king of kings, king of Khotan, Gurgamoya.

Rev: Chinese legend: "Twenty-four grain copper coin". British Museum