Amalric of Nesle

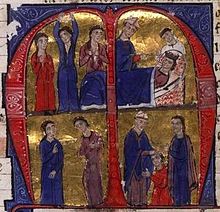

Amalric of Nesle (French: Amaury; died on 6 October 1180) was a Catholic prelate who served as the Latin patriarch of Jerusalem from late 1157 or early 1158 until his death.

Amalric focused chiefly on managing church property; he showed very little political initiative and, unlike many contemporary bishops in the crusader states, had no interest in military affairs.

Amalric was annoyed when the king allowed the Greek Orthodox patriarch of Jerusalem, Leontius, to enter the kingdom as the representative of Emperor Manuel I Komnenos, whose aid the king hoped to secure; Manuel recalled Leontius in order to maintain good relations with Amalric and, through him, with the papacy.

[1] Historian Bernard Hamilton considers it likely that his appointment was arranged by Queen Melisende, who was then reigning with her son King Baldwin III.

[3] At the peak of the church hierarchy in the Kingdom of Jerusalem was the patriarch,[4] who had a key role in the selection of the king because he was entitled to perform the coronation.

King Baldwin III, the leading barons, the patriarch, and the bishops held a council in Nazareth to deliberate on the matter.

[7] On 29 August 1167 the patriarch celebrated the king's marriage to Maria, a grandniece of Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos, at the Cathedral of Tyre [it].

After the Christian defeat at the battle of Harim in 1164, Amalric wrote an encyclical offering indulgences to those who would come to help the Catholics in the Levant; this remained his only contribution to the kingdom's political life.

[18] He, Archbishop Ernesius of Caesarea, and Bishop William of Acre[19] were carrying letters to Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, Kings Louis VII of France and Henry II of England, Queen Margaret of Sicily, and Counts Philip I of Flanders, Theobald V of Blois, and Henry I of Champagne.

[20] Though he escaped unharmed, Amalric was replaced as the head of the embassy by Frederick de la Roche, now the archbishop of Tyre.

[18][20] The king and the patriarch worked together cordially on the ecclesiastical organization of the kingdom, setting up the new bishoprics of Petra and Hebron in 1168.

Amalric received a confirmation from the pope that the other Orthodox sees without bishops, namely Jericho, Nablus, and Darum, would remain under the control of the patriarchate.

Amalric tried to offset his losses by usurping some of the revenues of the Holy Sepulchre, causing the pope to reprimand him after the canons complained.

Though he had left a young son, Baldwin IV, there was a debate about the succession because the boy had been exhibiting symptoms of leprosy.

[23] The High Court agreed that Baldwin IV was the best choice,[24] and Amalric anointed him and crowned him in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre on 15 July.

[26] The year 1177 saw the arrival of the Greek Orthodox patriarch of Jerusalem, Leontius, as the representative of the Byzantine emperor, Manuel I Komnenos.

[28] During Baldwin IV's reign the Ayyubid ruler Saladin united the Muslim-ruled lands of Egypt and Syria, encircling the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Hamilton notes that Amalric performed no acts of piety that might have made him a reputable religious leader, that the only alms he gave were for his own requiem, and that he instituted no special prayer for the kingdom in perilous moments such as Saladin's 1177 invasion.

[18] Hamilton concludes: No other Latin patriarch had ruled for so long: no other had made so little contribution to the life of the kingdom and of the church.