Patronage in ancient Rome

From the emperor at the top to the commoner at the bottom, the bonds between these groups found formal expression in legal definition of patrons' responsibilities to clients.

[3] Patronage relationships were not exclusively between two people and also existed between a general and his soldiers, a founder and colonists, and a conqueror and a dependent foreign community.

[6] The client was regarded as a minor member of their patron's gens, entitled to assist in its sacra gentilicia, and bound to contribute to the cost of them.

While the Roman familia ('family', but more broadly the "household") was the building block of society, interlocking networks of patronage created highly complex social bonds.

Both patricius, 'patrician', and patronus are related to the Latin word pater, 'father', in this sense symbolically, indicating the patriarchal nature of Roman society.

Allowing one's clients to become destitute or entangled in unjust legal proceedings would reflect poorly on the patron and diminish their prestige.

[citation needed] The complex patronage relationships changed with the social pressures during the late Republic, when terms such as patronus, cliens and patrocinium are used in a more restricted sense than amicitia, 'friendship', including political friendships and alliances, or hospitium, reciprocal "guest–host" bonds between families.

[18] Traditional clientela began to lose its importance as a social institution during the 2nd century BC;[19] Fergus Millar doubts that it was the dominant force in Roman elections that it has often been seen as.

A young man serving in a military capacity, separate from the entourage that constituted a noble's familia or "household", might be termed a vavasor in documents.

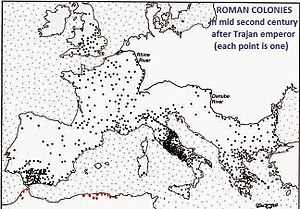

He also made many acts of kindness to the whole of Rome at large, including food and monetary handouts, as well as settling soldiers in new colonies that he sponsored, which indebted a great many people to him.

[6] Through these examples, Augustus altered the form of patronage to one that suited his ambitions for power, encouraging acts that would benefit Roman society over selfish interests.

[26] Extending rights or citizenship to municipalities or provincial families was one way to add to the number of one's clients for political purposes, as Pompeius Strabo did among the Transpadanes.

[27] This form of patronage contributed to the new role created by Augustus as sole ruler after the collapse of the Republic, when he cultivated an image as the patron of the Empire as a whole.