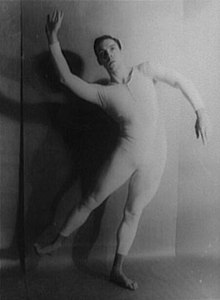

Paul Taylor (choreographer)

[7] Taylor's early choreographic projects have been noted as distinctly different from the modern, physical works he would come to be known for later, and have even invited comparison to the conceptual performances of the Judson Dance Theatre in the 1960s.

Specifically, Rauschenberg's series of “white” paintings resulted in John Cage’s composition, 4’33”, for which Taylor’s piece Duet (1957), was inspired.

On the same program was a work called Epic, in which Taylor moved slowly across the stage in a business suit while a recorded time announcement played in the background.

The Dance Observer critic Louis Horst published a blank column that stated only the location and date of Taylor’s performance as a review in November 1957 as a response to Duet, after which Martha Graham called him a "naughty boy.

The performance was still intended to provoke dance critics, as he cheekily set his modern movements not to contemporary music but to a baroque score.

While he may propel his dancers through space for the sheer beauty of it, he has frequently used them to illuminate such profound issues as war, piety, spirituality, sexuality, morality and mortality.

In Esplanade Taylor was fascinated with the everyday movement that people enacted on a daily basis—from running to sliding, to walking, jumping and falling.

In Private Domain, Taylor commissioned a set by renowned visual artist Alex Katz, whose rectangular panels obstructed the audience from seeing a portion of the stage depending on their vantage points.

[9] Other well-known and highly regarded or controversial Taylor works include Big Bertha (1970), Airs (1978), Arden Court (1981), Sunset (1983), Last Look (1985), Speaking in Tongues (1988), Brandenburgs (1988), Company B (1991), Piazzolla Caldera (1997), Black Tuesday (2001), Promethean Fire (2002), and Beloved Renegade (2008).

Many scholars and dance critics have established a categorization of Taylor's works and identified patterns surrounding his choreographic development.

This prompted scholars to identify a light/dark pattern in Taylor's choreography due to Scudorama’s apparent representation of evil in comparison to Aureole’s lyrical, sunny nature.

[10] Taylor collaborated with artists such as Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Alex Katz, Tharon Musser, Thomas Skelton, Gene Moore, John Rawlings, William Ivey Long, Jennifer Tipton, Santo Loquasto, James F. Ingalls, Donald York and Matthew Diamond.

His career and creative process has been much discussed, as he is the subject of the Oscar-nominated documentary Dancemaker, and author of the autobiography Private Domain and a Wall Street Journal essay, "Why I Make Dances.

"[11] Taylor was a recipient of the Kennedy Center Honors in 1992 and received an Emmy Award for Speaking in Tongues, produced by WNET/New York the previous year.

He received the Algur H. Meadows Award for Excellence in the Arts in 1995 and was named one of 50 prominent Americans honored in recognition of their outstanding achievement by the Library of Congress's Office of Scholarly Programs.

Thus far, dances by Doris Humphrey, Shen Wei, Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham, Donald McKayle, and Trisha Brown have been presented.