Maria Tallchief

In her autobiography, Tallchief explained, "As a young girl growing up on the Osage reservation in Fairfax, Oklahoma, I felt my father owned the town.

Looking back on Sabin many years later, Tallchief wrote, "She was a wretched instructor who never taught the basics, and it's a miracle I wasn't permanently harmed.

In her autobiography, she reminisced about time spent "wandering around our big front yard" and "[rambling] around the grounds of our summer cottage hunting for arrowheads in the grass.

[4] The day they arrived in Los Angeles, her mother asked the clerk at a local drugstore if he knew any good dance teachers.

[5] The California school moved Betty Marie back to the proper grade for her age but put her in an Opportunity Class for advanced learners.

At Beverly Vista School, Betty Marie experienced what she described as "painful" discrimination and took to spelling her last name as one word, Tallchief.

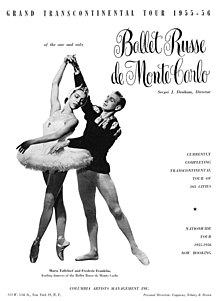

Mia Slavenska took a shine to Tallchief and arranged for her to audition for Serge Denham, director of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo.

[11][4] At the same time, the company was preparing to stage Agnes de Mille's Rodeo, or The Courting at Burnt Ranch, an early example of balletic Americana.

The New York Times dance critic John Martin wrote, "Tallchief gave a stunning account of herself in Nijinkska's Chopin Concerto ... She has an easy brilliance that smacks of authority rather than bravura," and predicted she would be a big star in the near future.

[11] In the spring of 1944, well known choreographer George Balanchine was hired by Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo to work on a new production called Song of Norway.

"[12] Balanchine continued to cast Tallchief in important roles, featuring her in a pas de trois with Mary Ellen Moylan and Nicholas Magallanes in Danses Concertantes.

Tallchief wrote: "The accent was sharp, the rhythm swinging and modern," and, "Performing the steps seemed more like an exercise for pleasure and enjoyment than work.

"[12] As the season wore on, Balanchine grew fond of her both professionally – The Washington Post called Tallchief his "crucial artistic inspiration" – and personally.

Danilova devoted a lot of her time to instructing Tallchief in the ballerina's art, helping her transform from a teenage girl into a young woman.

[14] A group of supporters of Serge Lifar, who was on leave while accusations of aiding the Nazis during World War II were investigated, led a vocal campaign to get rid of Balanchine.

[14] Upon her arrival in France, Tallchief was put to work immediately with roles in Le baiser de la fée and Apollo.

"Peau Rouge danse a l'Opera pour le Roi de Suede" [Redskin dances at the Opera for the King of Sweden], read a front-page headline.

[14] "La Fille du grand chef Indien danse a l'Opera" [The daughter of the great Indian chief dances at the Opera], read another.

[4] When the couple returned to the States, Tallchief quickly became one of the first stars, and the first prima ballerina, of the New York City Ballet, which opened in October 1948.

[5] Of her "Firebird" debut, Kirstein wrote "Maria Tallchief made an electrifying appearance, emerging as the nearest approximation to a prima ballerina that we had yet enjoyed.

[1][9] Noting the great technical difficulty of the role, The New York Times critic John Martin wrote that Tallchief was asked "to do everything except spin on her head, and she does it with complete and incomparable brilliance.

[4] Critic Walter Terry remarked "Maria Tallchief, as the Sugar Plum Fairy, is herself a creature of magic, dancing the seemingly impossible with effortless beauty of movement, electrifying us with her brilliance, enchanting us with her radiance of being.

[5] She created the lead role of "Prodigal Son," "Jones Beach," "A La Françaix," and plotless works such as "Sylvia Pas de Deux," "Allegro Brillante," "Pas de Dix," and "Symphony in C."[3] Her fiery, athletic performances helped establish Balanchine as the era's most prominent and influential choreographer.

[3] That summer, she appeared alongside Danish danseur Erik Bruhn in Russia, where she was recognized for "aplomb, brilliance, and dignity of the American style.

[4] Ashley Wheater, artistic director of the Joffrey Ballet, remarked, "When you watch Tallchief on video, you see that aside from the technical polish there is a burning passion she brought to her dancing.

"[1] William Mason, director emeritus of the Lyric Opera of Chicago, described Tallchief as "a consummate professional ... She realized who and what she was, but she didn't flaunt it.

"[1] During her first year at the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, Tallchief dated Russian dancer Alexander "Sasha" Goudevitch, the darling of the company.

Balanchine opened the car door for her, and when she got in, he sat in silence for a moment before saying, "Maria, I would like you to become my wife,"[12] "I almost fell out of my seat and was unable to respond," she recalled.

"[5] Time remarked "of all the ballerinas of the last century, few achieved Maria Tallchief's artistry, a kind of conscious dreaming, a reverie with backbone.

[9] Sandy and Yasu Osawa of Upstream Productions in Seattle, Washington, made a documentary titled Maria Tallchief in November 2007 that aired on PBS between 2007 and 2010.