Paul Wild (Australian scientist)

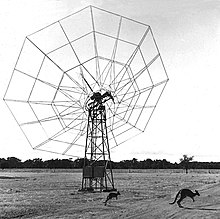

In the late 1960s and early 1970s his team built and operated the world's first solar radio-spectrographs and subsequently the Culgoora radio-heliograph, near Narrabri, New South Wales.

He retired from CSIRO to lead (from 1986) the Very Fast Train Joint Venture, a private sector project that sought to build a high-speed railway between Australia's two most populous cities.

On his "free" day each week he had been trained in the Home Guard, but his great interest in ships and the sea led him to join the Royal Navy.

His seagoing appointment for the following two and a half years, with 60 subordinates and 24 radar sets,[12] was the battleship HMS King George V, which eventually became flagship of the British Pacific Fleet.

Their instruments revealed for the first time the presence of charged particles and shock waves travelling through the solar corona, and their potential effects on "space weather".

Wild's work arose from the phenomenon of embryonic radar technology sometimes being jammed by mysterious interference, later discovered, in England, to be radio noise coming from the Sun.

At Penrith, 50 kilometres west of Sydney in the foothills of the Blue Mountains, a fairly primitive wooden aerial was pulled around with ropes, and every twenty minutes it was changed so that it pointed towards the Sun.

... At each meeting of the International Astronomical Union, highly competent specialists such as Wild [and Smerd and Christianson, headed by Pawsey] … were able to announce spectacular progress.

Staff members, who spent several days per week there, slept and ate in an adjacent single-roomed weatherboard hut with a table down the middle and camp stretchers around the sides.

The team deduced that the type II bursts were associated with shock waves coming out through the solar atmosphere at 1000 km/s and were associated, 30 hours later, with aurora in the Earth's night sky.

[34] Wild's team associated type III bursts with streams of electrons being ejected at a third the speed of light and taking less than half an hour to reach the Earth.

[35] There remained a few sceptics about this interpretation until, a decade or so later, American physicists using satellite data regularly detected bursts of electrons 25 minutes or so after solar flares.

When Ewen and Purcell in the US first observed the 1420 MHz transition in 1951, he went back to his report, generalised it to include the interstellar medium, and six months later published the first detailed theoretical paper on the hydrogen lines – a classic in the field.

It was de-commissioned in 1984 to make way for the Australia Telescope and transferred to the Ionospheric Prediction Service, where it is still used today for space weather monitoring of solar activity.

With George Gamow and instigator Harry Messel, he was a member of the inaugural trio who, from 1962, brought high-level science teaching to senior secondary students throughout Australia.

He took on the role after the first Independent Inquiry into CSIRO (the Birch Report[49] of 1977) pointed the organisation towards "filling a gap in national research with strategic mission-oriented work."

When asked in 1992 whether his appointment as Chairman rested "to an extent on the fact that you had put the division, and Australia, on the international map and you had this capacity for applying very fundamental work?

"[52] Wild recognised that CSIRO needed to adapt and provide scientific and technological leadership in a changing world, reflecting his maxim that "without excellence and originality, research achieves nothing."

[56] But many things did not involve smooth sailing: for example, as he put it, "I had terrible trouble over the Animal Health Laboratory when he [Wild's somewhat interventionist science minister, Barry Jones] wanted to close it all down, just when it was nearly finished being built."

This route was chosen because it would provide better access for people in the coastal south-east of New South Wales and eastern Victoria, who were very poorly served by transport links.

Although Sydney–Melbourne was later identified as the fourth-busiest air route in the world (busier than any in North America, or any in Europe apart from Madrid to Barcelona)[64] and the bureau had no firm data on transport markets in south-eastern Australia, its officials judged passenger fares would need to be set at a rate that would not be commercially viable.

[65] The bureau would not accept the French experience that the laws of physics (in which momentum is proportional to the square of the velocity) allowed much steeper gradients (hence much fewer cut-and-fill earthworks) than on low-speed railways.

"[66] After meeting with Morris later in September, Wild opined that "in many areas Australia needed desperately to dig itself out of the stagnation of 19th century thought."

He believed the reaction highlighted Australia's general malaise; he deplored the emphasis on the short term and the preference for patching up decaying and unprofitable systems, ignoring imaginative plans for the future.

In August 1987, after delay caused by uncertainties surrounding a potential takeover of their company, the BHP joined as the fourth, and subsequently foremost, partner.

The decision not to proceed with the original route to the east of the Snowy Mountains and through Gippsland was a difficult one for the VFT Joint Venture and for Wild personally.

[70] The decision earned the scorn of the original corporate supporter of the proposal, Sir Peter Abeles, a visionary who from the start had been attracted to the VFT's national development potential.

[16] When in the US Paul Wild spent hours with Margaret's son, Tom Haddock, also a research scientist, discussing general relativity, the origin of inertia, the clever way the Soviet scientists Landau and Lifshitz developed their arguments on field theory, and then-current experiments such as the Gravity Probe B satellite to detect the general relativistic Lense-Thirring frame-dragging effect from the Earth's spin.

In a 1995 interview Wild nominated his most significant achievement to be the building of the Culgoora radio-heliograph and providing the world with a unique eye to view and record moving pictures of rapidly changing solar activity.

278–290 of Stewart (2009), above, concerning the work of the CSIRO Division of Radiophysics at Penrith and Dapto; includes 25 publications authored or co-authored by Paul Wild.