Treaty of Riga

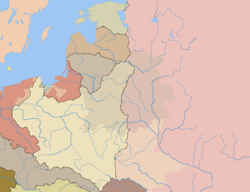

The Treaty of Riga established a Polish–Soviet border about 250 kilometres (160 mi) east of the Curzon Line, incorporating large numbers of Ukrainians and Belarusians into the Second Polish Republic.

Poland, by recognising the puppet states of the USSR and simultaneously withdrawing recognition of the UPR (its only ally in the Polish-Bolshevik war), was in fact giving up on the federation programme, while Russia approved of the fact that the whole of Galicia, as well as the territories of the former Russian Empire, inhabited largely by non-Polish people, were to be found within Poland's borders.

[4] This was a relief for the government of Poland, a country heavily damaged and exhausted by the war, who also wanted to conclude peace talks.

[6] The chief negotiators were Jan Dąbski for Poland[3] and Adolph Joffe for the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.

[5] The Soviets' military setbacks made their delegation offer Poland substantial territorial concessions in the contested border areas.

[3] The National Democrats did not want non-Polish minorities in the reborn Polish state to constitute more than one-third of the overall population, therefore, prepared to accept a Polish-Soviet border substantially to the west of what was being offered by the Soviets even though it would leave hundreds of thousands of ethnic Poles on the Soviet side of the border.

A border too far to the east would thus be against not only the National Democrats' ideological objective of minimising the minority population of Poland but also their electoral prospects.

[7] Warweary public opinion in Poland also favoured an end to the negotiations,[5] and both sides remained under pressure from the League of Nations to reach a deal.

Pressured by the National Democrat ideologue, Stanisław Grabski, the 100 km of extra territory was rejected, a victory for the nationalist doctrine and a stark defeat for Piłsudski's federalism.

[4] The Treaty of Riga, signed on 18 March 1921, partitioned the disputed territories in Belarus and Ukraine between Poland and Russia and ended the conflict.

The supporters felt that Ukraine had been betrayed by its Polish ally, which would be exploited by the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and contribute to the growing tensions and eventual anti-Polish massacres in the 1930s and the 1940s.

[3] While the Treaty of Riga led to a two-decade stabilisation of Soviet-Polish relations, conflict was renewed with the Soviet invasion of Poland during World War II.

The treaty was subsequently overridden after a decision by war's Allied powers to change Poland's borders once again and transfer the populations.

In the view of some foreign observers, the treaty's incorporation of significant minority populations into Poland led to seemingly insurmountable challenges, because the newly formed organizations such as OUN engaged in terror and sabotage actions across ethnically mixed areas to inflame conflict in the region.

[8][12][21] Nevertheless, many groups representing national minorities welcomed Piłsudski's return to power in 1926 providing opportunities to play a role in the Polish government.

[23] At least 111,000 were summarily executed in the NKVD operation in 1937/38, preceding other ethnic repression campaigns perpetrated during World War II, while others were exiled to different regions of the Soviet Union.

After the Soviet Union established its control over the People's Republic of Poland, the Polish-Soviet border was moved westwards in 1945 to roughly coincide with the Curzon Line.