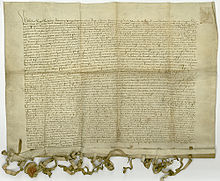

Peace of Thorn (1411)

In historiography, the treaty is often portrayed as a diplomatic failure of Poland–Lithuania as they failed to capitalize on the decisive defeat of the Knights in the Battle of Grunwald in June 1410.

However, large war reparations were a significant financial burden on the Knights, causing internal unrest and economic decline.

The Polish–Lithuanian army, suffering from lack of ammunition and low morale, failed to capture the Teutonic capital and returned home in September.

Heinrich von Plauen, new Teutonic Grand Master, wanted to continue fighting and attempted to recruit new crusaders.

[6] Three-day negotiations in Raciąż between Jogaila and von Plauen broke down and Teutonic Knights invaded Dobrzyń Land again.

[8] The Teutonic Order relinquished its claims to Samogitia but only for the lifetimes of Polish King Jogaila and Lithuanian Grand Duke Vytautas.

Considerable ransoms were recorded; for example, the mercenary Holbracht von Loym had to pay 150 kopas of Prague groschens, or more than 30 kg of silver.

[13] The Peace of Thorn settled the ransoms en masse: the Polish King released all the captives in exchange for 100,000 kopas of Prague groschen, amounting to nearly 20,000 kilograms (44,000 lb) of silver payable in four annual installments.

However, further payments were difficult to collect as the Knights emptied their treasury trying to rebuild their castles and army, which heavily relied on paid mercenaries.

Vytautas claimed that all territory north of the Neman River, including port city Memel (Klaipėda), was part of Samogitia and thus should be transferred to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

[18] In August 1412, Sigismund announced that the Peace of Thorn was proper and fair[19] and appointed Benedict Makrai to investigate the border claims.

[22] Increased taxes and economic decline exposed internal political struggles between bishops, secular knights, and city residents.