Pediatric advanced life support

The course teaches healthcare providers how to assess injured and sick children and recognize and treat respiratory distress/failure, shock, cardiac arrest, and arrhythmias.

The most essential component of BLS and PALS cardiac arrest care is high quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

In the two-fingers technique, the provider uses their index and middle finger to press down on the infant's sternum, below the nipples.

[2] PALS teaches a systematic assessment approach so that the health care provider can quickly identify any life-threatening conditions and treat them.

The PALS systematic approach algorithm begins with a quick initial assessment followed by checking for responsiveness, pulse, and breathing.

Airway - assess airway patency (open/patent, unobstructed vs obstructed) and if the patient will need assistance maintaining their airway Breathing - assess respiratory rate, respiratory effort, lung sounds, airway sounds, chest movement, oxygen saturation via pulse oximetry Circulation - assess heart rate, heart rhythm, pulses, skin color, skin temperature, capillary refill time, blood pressure Disability - assess neurological function with AVPU pediatric response scale (alert, voice, painful, unresponsive), pediatric Glasgow Coma Scale (eye opening, motor response, verbal response), pupil response to light (normal, pinpoint, dilated, unilateral dilated), blood glucose test (low blood sugar / hypoglycemia can cause altered mental status) Exposure - assess temperature/ fever, signs of trauma (cuts, bleeding, bruises, burns, etc.

[4] Providers must be able to identify respiratory problems that are easily treatable (e.g., treated with oxygen, suctioning/ clearing airway, albuterol, etc.)

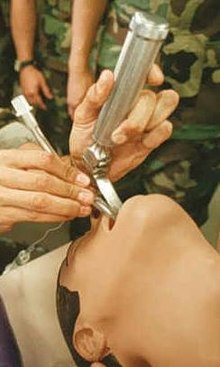

Surgical advanced airways are typically performed when intubation and other less invasive methods fail or are contraindicated or when the child will need long term mechanical ventilation.

[4] Shock is defined as inadequate blood flow (perfusion) in the body, causing tissues and organs to (1) not get enough oxygen and nutrients and (2) have trouble getting rid of toxic products of metabolism (e.g., lactate).

It is important to recognize and treat shock as early as possible because the body requires oxygen and nutrients to function and without them, organs can eventually shut down and people can die.

[3] Common signs of shock include weak pulses, altered mental status, bradycardia or tachycardia, low urine output, hypotension, and pale, cold skin.

Hypotensive/ decompensated shock is when the body cannot maintain systolic blood pressure in the normal range, and it becomes too low (hypotensive).

Common causes include tension pneumothorax, cardiac tamponade, pulmonary embolism, and ductal dependent congenital heart defects (conditions that worsen when the ductus arteriosus closes after birth) (e.g., hypoplastic left heart syndrome and coarctation of the aorta).

However, if cardiogenic shock is suspected, kids should receive less fluids over a longer time (e.g., 5-10 ml/kg over 15-30 min).

Tension pneumothorax is treated with a chest tube and needle thoracostomy which allows the air to get out of the pleural space.

Ductal dependent congenital heart defects are treated with prostaglandin E1/ alprostadil which keeps the ductus arteriosus open.

For this reason, it is important to treat respiratory failure and shock early so that they don't progress to cardiac arrest.

These arrhythmias are more common in kids with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, cardiac channelopathies (e.g., long QT syndrome), myocarditis, drugs (e.g., cocaine, digoxin), commotio cordis, and anomalous coronary artery.

The goals of treatment are to obtain return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), meaning that the heart starts working on its own.

After starting chest compressions, the provider should (1) give ventilations (via bag mask) and oxygen, (2) attach monitor/defibrillator pads or ECG electrodes to the child so that defibrillations (aka shocks) can be given if needed, and (3) establish vascular access (IV, IO).

This 2 minute cycle of CPR and rhythm assessment should continue until it is determined by the providers that further management is unlikely to save the patient.

Throughout CPR and rhythm assessments, the providers should be treating any suspected reversible causes of cardiac arrest (H's and T's listed above).

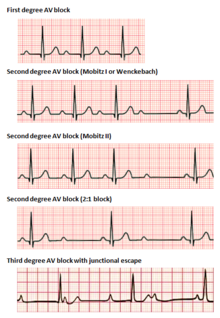

[2] Types of bradyarrhythmias Providers should follow the AHA's Pediatric Bradycardia With a Pulse Algorithm.

Bradyarrythmias with signs of shock can be treated with epinephrine and atropine in order to increase heart rate.

[5] Types of tachyarrhythmias Providers should follow the AHA's Pediatric Tachycardia With a Pulse Algorithm.

Management of tachyarrhythmias depends on if the child is stable or unstable (experiencing cardiopulmonary compromise: signs of shock, hypotension, altered mental status).

Unstable tachyarrhythmia is treated with synchronized cardioversion - initially 0.5-1 J/kg but can increase to 2 J/kg if smaller dose is not working.

If wide QRS/ VT with regular rhythm and monomorphic QRS, the provider can give adenosine and should consult pediatric cardiology for recommendations.

[9] PETA says that hundreds of PALS training centers have begun using simulators in response to concerns regarding the animals' welfare.