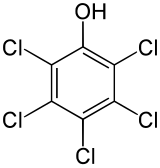

Pentachlorophenol

[5] Some applications were in agricultural seeds (for nonfood uses), leather, masonry, wood preservation, cooling-tower water, rope, and paper.

Also, general population exposure may occur through contact with contaminated environment media, particularly in the vicinity of wood-treatment facilities and hazardous-waste sites.

Elevated temperature, profuse sweating, uncoordinated movement, muscle twitching, and coma are additional side effects.

Long-term exposure to low levels, such as those that occur in the workplace, can cause damage to the liver, kidneys, blood, and nervous system.

Accumulation is not common, but if it does occur, the major sites are the liver, kidneys, plasma protein, spleen, and fat.

Unless kidney and liver functions are impaired, PCP is quickly eliminated from tissues and blood, and is excreted, mainly unchanged or in conjugated form, via the urine.

Biomagnification of PCP in the food chain is not thought to be significant due to the fairly rapid metabolism of the compound by exposed organisms.

However, PCP is still released to surface waters from the atmosphere by wet deposition, from soil by run off and leaching, and from manufacturing and processing facilities.

Finally, releases to the soil can be by leaching from treated wood products, atmospheric deposition in precipitation (such as rain and snow), spills at industrial facilities, and at hazardous waste sites.

PCP can be produced by the chlorination of phenol in the presence of catalyst (anhydrous aluminium or ferric chloride) and a temperature up to about 191 °C.

In the United States, any drinking-water supply with a PCP concentration exceeding the MCL, 1 ppb, must be notified by the water supplier to the public.

PCP was widely used in Chile until the early 1990s as a fungicide to combat the so-called "blue stain" in pine timber under the name of Basilit.