Percy Molteno

Although this was originally set up as a syndicate with other members of his family (particularly his brothers William and John Molteno), he soon shared his discoveries and influenced many other shipping companies to install refrigeration chambers on their vessels.

Those views made him a divisive figure both inside and outside the Liberal Party, of which he was a member: Winston Churchill once refused to attend a dinner if they were sitting together, and Henry Simpson Lunn reports fearing that his windows would be smashed if word got out that Molteno was present at his club.

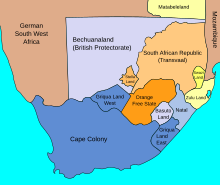

[13] In the early 1890s, the rise of pro-imperialist politicians such as Cecil Rhodes, Joseph Chamberlain and Alfred Milner heralded a change in the foreign policy of the UK government regarding Southern Africa, and the earliest signs of the coming war.

From very early on, Molteno foresaw the nature of the upcoming conflict and, through his correspondence with the leading politicians of the day, sought to warn them, and attack "official ignorance in high places of the realities in South Africa".

[2] As the war drew nearer, he threw his influence and fortune behind the minority "peace party" (which now included his colleagues "Onze Jan" Hofmeyr, Jacobus W. Sauer and John X. Merriman), and he severed business relations with Rhodes and other prominent figures, whom he saw as instigators.

In 1896, after the Jameson Raid, he wrote to the William Schreiner: In the years following the Boer War, Molteno withdrew from the shipping trade and devoted both himself and his remaining fortune to postwar humanitarian efforts in South Africa.

Having returned to South Africa to see what he could do to "salvage something from the wreckage"[2] and experience first-hand where need was most urgent, Molteno traveled extensively through the war-ravaged country, setting up relief funds and even adopting war orphans.

[16] Furious about Lord Kitchener's use of scorched earth tactics and concentration camps against the Boers, he also continued the work that he had started during the height of the war with Emily Hobhouse, exposing the atrocities and setting up institutions for the rehabilitation of survivors.

[17] Molteno entered the British House of Commons as the Member for Dumfriesshire in 1906, and soon used his increased parliamentary influence in the direction of the granting of full Responsible Government to the "ex-Republics" in southern Africa.

However, the political predicament on the eve of Union was that it course of action was supported only by a few white liberals and black politicians in the Cape, and the overwhelming majority of the predominantly-white electorate across Southern Africa was strongly opposed to that outcome.

[24] Developments after the Union like the rise of Afrikaner nationalism and apartheid led to his disillusionment with South African politics and his increasing devotion to humanitarian issues such as the Vienna Emergency Relief Fund, which he started in 1919.

In South Africa, he publicly supported and donated large sums of money to the fundraising activities of John Dube and the infant African National Congress (ANC).

In his personal beliefs, he was an atheist (though he preferred the term "Lucretian") and founded the Common Sense magazine where he intended writers to present articles on controversial issues of the time that were based on reason, evidence and ethics, rather than on emotion and nationalism.